When Vic Greener, former aspiring Hollywood actor, buys a foreclosed home in the Hudson Valley with money he got from a toothpaste commercial, it sets a series of actions into his life that will, eventually, result in his death. He moves into the first one with his wife Heather, but when a 7-foot-tall garbageman moves into the duplex, encroaching on their lives as Heather pulls freakishly large produce from her garden, things get eerie. Same as when their mute toddler opens his mouth only to ask about an unearthed necklace. As Vic falls deeper into the foreclosure business, and as Junior grows up and works with his father before heading off with some dreams of his own, it’s clear the houses are a distraction from his abandoned dreams.

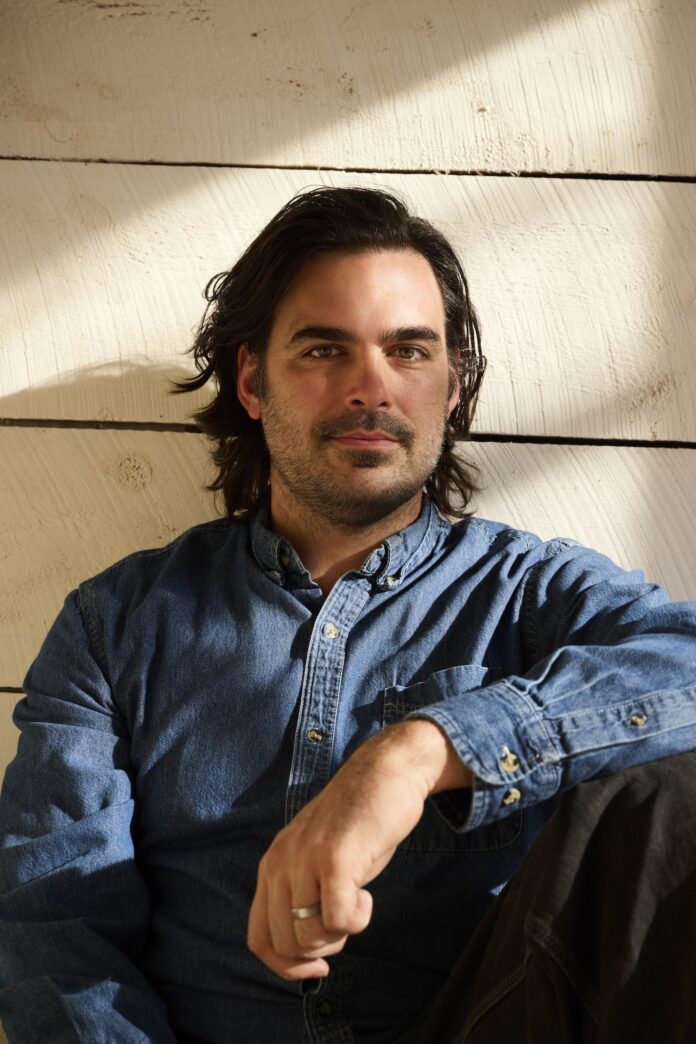

OurCulture sat down with Harris Lahti to talk about Foreclosure Gothic, the uncanniest book of the year so far, unsettling children, and family legacy.

Congratulations on your debut novel! I know portions of it were published before, but how does it feel so close to release?

My life’s kinda organized in this way where I have two kids, I work full time, I’m pulling my house together, and I’m just really hoping it’s received well. I’m just looking for validation to continue doing this thing! [Laughs]

I liked that the chapters were vignettes, connected stories within a larger story. Was this what you had in mind for the novel?

I don’t think I was writing with a goal in mind. The second chapter, “Sugar Bath,” I wrote in one sitting, the one with graves in the basement. And I was reading certain books at the time that influenced the style and it came out as this fully formed one from the ether. Then I wrote the last chapter, trusting this voice and riding in the same way. The way I wrote it was trying to piece these stories together to make them make sense. As you populate the timeline with different stories by pulling ideas out of each of those, it allows this organic, intuitive structure to establish itself.

I think you use time so interesting in the novel — why did you want it to be a family saga between the Greeners instead of a more isolated period?

Man, it’s so horrible that time gives things meaning. I heard that in The White Lotus, and I was like, ‘Crap, that’s what books do!’ Anyone going to live long enough is clearly going to face the decision whether or not to have children based on their socioeconomic predicament, their character. The episodic nature of it is a good way of cutting out the fat and avoiding the more pedestrian and domestic normalcy that could establish itself and turn a story like this into a slog. I like the idea of getting in late and getting out early. The leaping structure allows each chapter to reinvent itself and build its own world and feel more lived-in. I’m a big believer in discovery being more important than inventing — so mining the synapses between the stories to create other stories is more exciting when there’s more to work with.

You renovate houses in the Hudson Valley — is it as eerie as you depict it in the book?

[Laughs] The photos are real, and a lot of the stranger elements in each story are true. If ghosts exist, I would have seen one. I might be the wrong person to ask that question just because maybe you think it’s eerie, but I remember being 4 or 5 and driving up to one of the houses my dad just bought on this gravel road. He’s pulling out junk and laying it in the road, like, ‘These toy model cars are gonna get me $500.’

But there are darker aspects to it. For example, the house behind me was the first house I renovated with my own money. There’s just layers of things you get through where you learn the whole family story. You walk into the living room and there’s a TV, and armchair, some pills on a table, and you can kind of see this person was sleeping here, taking pills, that was their life. But below all the garbage accumulated around the area, there’s signs of a more organized domestic life. You realize that as you go through the papers and read all the receipts, what has more or less dust on it, you understand that the woman’s parents died, she was a junkie, just lived in the house until it was foreclosed on. It’s a terrible story, but underneath you see that this was an actual life; there was happiness, there were garden beds beneath the brush.

Tell me a little about the unsettling photos interspersed in the book — most were taken by you or family members, right?

Yeah, that raccoon picture — a photographer was living at my parents’ house and set up a camera. She was into death, she’d take pictures of dead birds and dead animals. She knew there were coyotes, bears in the woods, so she put this raccoon out and set-dressed it, thinking an animal would come and eat it, but that’s not what happened. So I put that in the book and wrote a story around that image, just because it was so strange and weird. It was saying something about nature I was interested in. And [after that], I realized I had the grave one story was based on, because my father pulled it out of a basement. So I posed it in the basement and used it the same way. I kept thinking about the different stories and things started to calcify.

Talk to me a little bit about how you crafted the more chilling aspects of the book: I’m thinking about the tall garbageman, the toddler who speaks only to explain the history of an unearthed necklace.

I think with fiction, there’s this phrase, to ‘dilate the attractor.’ In that garbageman story, the most tension being created was the bodily threat. So, why not make him enormous, which would make him more threatening? A lot of the time, you’re playing on those evolutionary impulses and fears. Especially inside of this world, where realism and surrealism are blending, which I think is an interesting aspect of the gothic genre. The kid thing — I think kids were always mysterious to me. The book was finished before I had children, and kids had this wisdom and simplicity that made me uneasy. Not to mention, watch any horror movie and there’s always a kid doodling one of their relatives covered in blood or something.

Vip flipping all of these foreclosures felt like a virus, or an addiction; he says only one more, then he gets invested and finds another project. Is that how you pictured it?

Yeah, it’s a warning for me, it’s a warning for my dad. My dad was an actor, and he ran the same kind of arc I did, then around this age, you have kids and realize you have to provide for them. It’s nice to have a house, it’s nice to have nice things. There are certain comforts to having money, which I think cut against what it means to be an artist. I had a lot of anxiety and fear about that being my life, my dad’s life. There’s an impulse that you have to submerge or validate success, however minor, as something you should be doing.

So you’re Junior!

Yeah! Well, the way I’ve been thinking about it — Stanislavski was the pioneer of method acting, and one thing he talks about is emotional authenticity and putting your lived experiences into another character, to make that representation realer. As a writer, it’s not very interesting to watch someone write — it’s very heady, cerebral. By grafting it onto my dad’s story, it provides a more concrete and uncanny device to play with that I think is much more compelling on the page. Action is what drives drama. My dad will be the first person to tell you — he refers to himself as the main character of the book. I keep reminding him, ‘No! This is what my life is and could be!’

When Vic and the garbageman start building the treehouse, Heather thinks of it as “a literal shantytown overhead growing to resemble the madness contained within his mind.” But to me, Vic seems content with this random pivot in his life. Is this just her overthinking his involvement?

No, I don’t think so. I think Vic is high on success at that moment. If it’s too good to be true, it probably is. I think he’s lying to himself for the expediency that will open up for him with his future. At that point in the story, I think he’s harboring resentment, but he’s buried it so deep that this new thing is starting to emerge as his creative outlet in a way that he’s gonna double down on; it’ll provide him with that sense of contributing and not being selfish or living up to his mother-in-law’s feelings about him.

So Heather sees it all along?

Yeah, I think she’s an interesting character because she sees things very clearly, and her love for Vic is kind of unconditional, and there’s a certain level of horror contained within someone loving you unconditionally, because there’s no check or balance on your own actions. You’re left to make decisions that are wholly on your shoulders. Operating in a vacuum is a very scary thing.

I think the chapter where Junior decides to stay in Costa Rica, abandoning his family to become a novelist is my favorite — it shows the difference in passion and goals between him and his father so well.

The best short stories are the ones that are unique but also relatable, and we all have a Costa Rica we want to escape to, to live out our dreams, that are much harder to achieve than we’d ever imagined, given time and space. Once it’s on your shoulders to do the thing you’ve always wanted to do, your abilities change and warp.

I thought the grotto chapter was so revealing — an old acting friend invites Vic to a party where they do coke, and he and Heather’s relationship takes an interesting turn in the car ride back home. What did you want to do with this section?

I think it’s another example of Heather remembering the passion of their life before their kid. Vic has this feeling of being over the hill, then stepping back into it, then feeling even more over the hill in the aftermath. Just as a reminder that some doors are better left shut. I think that’s helpful for him in his current life. I really like deploying sexuality and eroticism in their relationship because I feel it says things they’re not willing to say to each other and never will, but in the later chapters, it’s a way of forgiving and remembering what brought them here. Even if it’s too horrifying to draw those demons out any further into the opening. It’s this thing you do when you’re completely naked, but there’s another feeling of nakedness beneath it all. Psychologically, are they naked? I’m not sure.

Vic’s about repression, you know — every step of the way, he’s repressed. When it gets closer to that core, the more elevated and heightened and energetic and frenetic the stories become.

Yeah, the book ends circularly, with Vic’s passion being what causes his downfall. Was this always the plan?

No! I don’t think writing is magic, but there are moments when you’re writing where it comes to you in a way that feels outside of you, and the ending was another example of that. It was something that I felt I endured, and walked around gloomily for days afterward. I always trust that one sentence opens the next one, and so on, and then you have pages that are coherent and have an organic flow that I always try to cultivate.

Sort of like improvisation.

That part, for sure. It is kind of an Oedipal novel, in the way he had to go. I’m not against stories ending with a big bang; the more muted, cerebral stories are the more exciting. I saw a Goodreads review where someone said [Foreclosure Gothic was] “if blue balls was a book.” It’s the idea of edging you towards a climax and then not giving you one. Subconsciously, I felt like there needed to be this moment of true horror we step into. I love horror movies, and my favorite parts of them are the first half-hour. Watching people live their lives, it charges everything with this importance, because you know it’s moving toward something foreboding. Maybe I just wanted to provide that climax, but it was fun as shit to write.

Finally, what are you working on now?

The novel I’m working on is a house book — I want to write three of them, just to get the trilogy. I live by this hyperpacificist Christian community — they immigrated here during World War II. There’s 300 of them. I live in the woods. They’re back there! [Turns laptop around] It’s beautiful. There’s lakes and pathways and a school. They’re the sweetest people; the women wear skirts and the men look like farmers. Everything they do is so nice. But what’s interesting to me is how shitty they make me feel. They turn every misdemeanor I commit into a felony, by proximity, because I’m not living that lifestyle. I know they’re not judging me, but there’s this weird sense of judgement I impose on myself. The book I’m working on is about a guy who buys a foreclosed house, is fixing it up, going through problems with his wife, as these people continue to swarm and make him feel worse about himself. It’ll happen either in the house or at Lowe’s. Those are the two settings.

Foreclosure Gothic is out now.