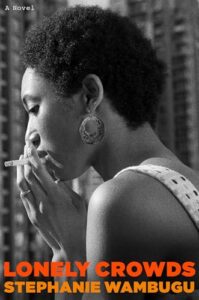

When Ruth spots Maria in the line to get clothes for the new school year as a child, she’s immediately entranced. Not for any particular reason, but Ruth, a daughter of Kenyan immigrants living in New England, needs something to latch onto. So begins her life of lightly trailing behind, returning back to Maria even through snowy nights where she may have been kidnapped by their teacher, through college, where Ruth’s artsy boyfriend irritates Maria, and afterwards in Manhattan, where Maria’s confessional art and protective girlfriend Sheila alienates Ruth, who suddenly feels cut out of the only deep relationship she’s had in her whole life. As Ruth navigates the art world in turn, dealing with tokenizing gallery owners and her earnest, supportive husband, she wonders if she can function without Maria before she returns with an intense plea to commit to a life together. Robust, meaningful, and poignant without losing its humor, Stephanie Wambugu’s standout debut Lonely Crowds narrates a complicated friendship for the ages.

Our Culture sat down with Wambugu to talk about psychoanalysis, entitlement, and friendship.

Congratulations on your debut novel! How does it feel now that it’s almost out?

I feel good, strangely. I don’t think the panic is really hitting me. I’m sure it’ll come at the most inopportune moment. But I feel happy, and so far people have been very positive and generous about it.

I saw a Goodreads review that said the novel could be the length of A Little Life, and I agree. Did you ever think about expanding it?

I will say that my drafting process is that just as much as I keep, I throw out. There’s so many scrapped pages from this novel that never made it, and I’m not very sentimental about throwing out parts of the draft. I think that sort of sensibility will naturally yield shorter books. I will tell on myself and say I saw the same good review. I don’t check my Goodreads anymore, but I used to, because I couldn’t help myself. I wondered, maybe there’s another book out here like this that should be 700 pages, it’s just not my impulse. I can’t see it being anything other than what it is.

Tell me a little bit about developing Ruth’s voice. I thought she was entertainingly detached, but very astute.

I felt there’s something really capacious about a child narrator, which she truthfully isn’t, because it’s an adult woman recounting her childhood. But I think there were a lot of opportunities to use her naiveté strategically in order to survey the world around her since the basic mechanics of it were lost on her. Using her as a fly on the wall or something. But then as an adult, she’s very cynical and detached as you say. I like those two extremes — that she can be at once standoffish and aloof, and also be this sponge and repository for what’s going around her when you’re in the section where she’s a child.

You write in the acknowledgements that this is a book about friendship, and I’m curious why you chose such a fractured and complicated one to explore.

The funny thing is the emphasis on it being such a troubled friendship only really occurred to me after the book was sold. My feeling was like, ‘It’s not that bad!’ I don’t know, especially when you’re younger and your life is so enmeshed with your peers and you spend more time at school than you do sometimes at home, I feel like it’s very common to have these codependent, tense and fraught friendships. As far as the kinds of things I’ve seen, I didn’t even think they were that antagonistic. But of course I reread it and I go, ‘Yeah, they’re being explicitly cruel to one another.’ But I also think one of the yardsticks for how close you are with someone is how much you can have really intense conflict and this real ambivalence with them. An acquaintance [would] would never provoke these strong feelings. In order to make them seem close, they needed to have what you described as a very fractured relationship.

Why do you think Ruth falls so heavily into Maria’s orbit? Is she just a respite from the monotony of the town?

For one thing, why do we fall into anybody’s orbit? It’s hard to find someone compelling until after the fact. Maybe to illustrate what I mean, for the past year, I was in psychoanalysis, and you’re encouraged to talk about the analysis itself in addition to what other material you bring into it. In the final session, I was able to say, ‘I didn’t like this about our relationship, I found you to be this way,’ etc. And my analyst would tell me, ‘I found you to be this way.’ It’s sort of like a breakup where you’re able to then apprehend what happened, only when it was over. Similarly, when a relationship starts to disintegrate, you’re able to say, ‘That’s what their personality was like. That’s what drew me to them.’ In the midst of it, it’s hard to articulate why you even find someone compelling. Ruth is trying to figure out why she finds Maria so compelling; because it’s written in first person, you get all this information about Maria through Ruth’s subjectivity. It’s not totally verifiable that she’s so special and charming. If you were to have another authority come in and say, ‘This person is ordinary,’ it would really cause Ruth’s narrative to unravel. She insists on her friend’s exceptionality, but it’s unclear whether or not that’s true.

Back to that therapy bit, I don’t think I could handle it if someone said, ‘Here’s something you did that I didn’t like.’

I guess it wasn’t stuff that she didn’t like, because they’re not making judgments, it’s more observational. They all go speak to one another to debrief, and I’m sure then there’s opportunity to be judgmental. But I guess it was moreso, ‘This is what informed the relationship I had with you.’ I think it’s incredible how vulnerable you are when you’re in analysis. These people are incredibly influential over your life, and you don’t really know them from any other stranger. It was such a strange period in my life. I want to do it again, but I don’t know that it has a positive relationship to my writing. It was hard to be generative at that time, maybe because I was metabolizing all of the things I was thinking about so much already in analysis, that by the time I sat down to write, I felt emotionally spent.

One explanation for Ruth’s trance may come when you write, “I had the sense to know that if you find someone better or more beautiful, you support them.” Do you think this is true?

I don’t know if I would personally put that into practice in my life, but there is a Saul Bellow story, “A Silver Dish,” where he says something like “We love selfish people because they ask for what we can’t.” And we give it to them! I think people respond quite well to entitlement. Calling someone entitled is an insult, but if you watch how entitled people operate in the world, others are giving them what they want. I’m glad you find it funny, because I think it’s kind of a joke, where you have to defer to special people, but I do think that Maria just behaves in a way that she expects preferential treatment. She found the perfect person to give it to her.

I thought she was so funny. There was one line where she was counting her woes, and it ended like, ‘And I don’t even have a cell phone!’

[Laughs] Well, that’s me. Some people have all the luck and I don’t even have a cell phone. That’s definitely how it feels when you’re licking your wounds and you’re like, ‘And I don’t have this pair of shoes.’ I’m the most beleaguered person in the world.

It seems like people are always abandoning Ruth — Maria one snowy night as children, and later in college, her boyfriend James. Why do you think she remains loyal, or at least hopeful?

Aw, that’s such a sad question!

I was getting sad when I noticed it!

Well, totally. I think you have to have a bit of amnesia in order to fall in love or get close to people again. I think if people really remember the patterns in their romantic lives or childhood and acted accordingly, you’d completely be a shut-in and never try again. She’s trying to be optimistic. And while she can be kind of jaded, that could be a pose to conceal a real hopefulness. I feel she is a romantic person. The book opens with her talking about being a devoted person. Devotion is an integral part of her personality and worldview. I think she does just want to be someone’s acolyte or disciple.

I like that Ruth’s sexuality is always in question, never defined — she doesn’t reflect much on it until Maria says “Everyone can tell you aren’t attracted to men.” Was it a conscious choice to have her so repressed?

Yeah, in a way, because I think some personalities are more interested in making themselves legible in that way. There are people I know who see coming out as beside the point. Maybe they’ve had relationships with men and women alike, textbook bisexuals, but would never call themselves that. It’s interesting why people do or don’t disclose that. It’s not even necessarily clear that her parents are homophobic, and I think that ambiguity was important. I think she has a strained relationship with them, but I don’t think it would have been so catastrophic to come out. But, like, come out as what? That’s the lingering question, and I’m not really sure what her deal is. When I was re-reading it recently I was like, ‘Maybe she’s just asexual.’ I guess I wanted it to seem like she’s trying things on for size. Trying to find what it is that she finds compelling, and ultimately I’m not sure if she finds anything.

After Ruth is engaged and she confesses to feeling pressure to say yes, Maria says, “How would that look? That’s the quintessential question of your life.” Why did you want to write a character so concerned about outside influence?

Even though this ends up not being the most important thread in the book, she comes from this Kenyan family, and it’s not like they go to a cosmopolitan city or anything, it’s actually very similarly religious and insular. It kind of mirrors the conservatism of her family, even though they’re not the most conservative people in the world. They’re certainly living in a way that’s different from the peers she has in college, or the milieu she enters in New York City. I think in a culture like that, those early cultures she was a part of, optics are really important, maybe more important than what’s actually happening. The things I think artists place emphasis on, like self-expression, pride, individuality, are not things that are celebrated in a culture that’s more collectivist and concerned with how things look. That’s a source of tension between her and Maria, because Maria is eager to be in a world where she can announce who she is and make this fairly autobiographical art. That’s another distinction between the two of them — Ruth is not really making art about herself. It’s not confessional. Whereas Maria’s work is much more about her personal history, it uses footage from her own life, she’s more comfortable disclosing these things about herself.

Maybe this is more about what I observe about being a young American now that has a different first culture, but I’m surprised how little people care about how they come across. Or a lack of obligation. I don’t think I’m uptight, but sometimes I think a little more shame might be… People are really shameless! Maybe in terms of respectability. I think people are incredibly self-conscious about not wanting to be seen as cringy or have a real fear of being embarrassed. I think about, like, politeness, manners, and obligation. I think about flakiness. This is the most benign example, but I can’t imagine my mother, for example, cancelling on someone at the last minute. Maybe it’s a generational thing. It’s so amorphous because it might be something that belongs to a generation, it might be because of the culture someone comes from, but there’s a social cohesion that is falling apart. But maybe it needs to fall apart for people to enjoy their individuality. It comes at a cost.

I thought that how Maria and Sheila behaved as a couple was so real and so infuriating, how they both let the affect the other, or “corrupt,” as Ruth thinks. What was the inspiration for this relationship?

Should I name names? [Laughs] I was thinking the other day that there’s nothing worse than someone who’s a bit unhinged finding their match in a romantic partner who is also unhinged. Because then there’s no baseline anymore, you can endlessly spiral and see completely delusional behavior as normal. The goalposts keep moving. People can be enabled in the worst way by their partners, and this situation between Maria and Sheila is such a pressure cooker because they also have endless resources. As far as young twentysomethings in the city are concerned, money isn’t really an object, so there’s a certain insularity to the way they live. I don’t think either one is willing to reel the other in. It’s troubling to watch one person being opportunistic or out-of-touch, but when you have a couple, it can be exponentially worse.

Ruth drunkenly gets into an argument with an artistic friend who said that her paintings weren’t “African enough.” Ruth says that her paintings will outlive Africa, and America, for that matter. What did you want to explore with that conversation?

Typically if she were sober, she’d take it on the chin and not say anything, completely internalize it. She’s an incredibly porous person and up until that point you see her taking on the judgements of other people as fact. Primarily from Maria but also her parents; she completely accepts the characteristics that are assigned to her externally. She has this evening where she’s a little bit loose because she’s taken these drugs and been drinking. I mean, she’s ranting. It’s a ridiculous, grandiose thing to say. Basically, she’s saying, I’m above those constructs. There was a whole cultural moment where a lot of rappers would say, ‘I’m not a rapper, I’m a musician.’ And I think it’s people not wanting to be ghettoized or marginalized in a genre they see as not universal. Saying someone is an African artist maybe implies their work is not as universal as a European artist. I think now in our generation, those questions are kind of besides the point, and I can’t imagine someone asking, ‘Do you see yourself as a Black writer, or a writer?’ It seems like those have been put to bed, but I think that’s what she’s trying to express. These identity markers are not meaningful to her, and she’s raging against them. She has many moments like that, and I wonder where she ultimately lands. There’s also a moment later where a Black student comes up to her and says, “It’s so wonderful to have a Black professor that cares so much about us,’ and Ruth doesn’t know who she’s talking about. Looking around like, ‘I don’t know what you mean.’ So maybe those are linked moments, her rejecting that categorization.

In the 90s, Ruth spends time with gallery owners and curators who are in the process of collecting Black and African art, because they say, “Black artists are really hot right now.” I was wondering what you thought about the overlap between appreciation and fetishization.

Part of the reason I set the book when I did was because I think a simpler book could have been written about the moment after Black Lives Matter, and I’ve said this before, but art has so many parallels in response to the kinds of state violence. It was first Trayvon Martin, but even moreso, after George Floyd, there was a huge boom in the market for Black artists, and it’s very similar at the time this novel is set. There’s many articles written about that now — paintings that were selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars can’t be sold at all. I think then, like now, you can’t know if someone wants your work because they want to tokenize you or if they want your work because of its merit. You have to decide on your own if your work has merit. I don’t think people are going to leave money on the table. On one hand I think there’s something cynical about feeling like an artist selling a painting or a writer selling a book is a recourse from the violence that’s done to the poorest members of their racial group. But at the same time, people need a livelihood. I think she has to deal with both of those things.

By the time the novel opens, you see she’s had real success; she has this sold-out show, she has a job teaching, all the trappings of a successful artist. I think her bitterness is because of a feeling that her success is unearned, or came at the cost of certain kinds of integrity, or her work is framed in a certain way she’d preferred for it not to be framed, and the interpersonal sadness about the relationship that maps onto her career with her friend who had the same trajectory, but didn’t seem to care about cashing in and making the money that was available to her. And the novel opens with someone telling Ruth, ‘It’s a really good time to be an African artist.’ I guess the other side of it is, if there’s such a thing as a good time to be an African artist, is there a bad time too? What happens when everyone packs up their things and goes on to the next thing? It’s not really a sustainable model to collect people on the basis of identity and then abandon them when it’s no longer lucrative.

Finally, what’s next for you as a writer?

I’m working on a second novel, and I’ve been working away at it since I was in grad school. It’s about a young writer, she’s lovesick, in a bad romantic situation. I’m reluctant to say more because I think tomorrow I could scrap it and change it drastically, so I don’t want to be wedded to what I say. What I do know is that I’ve titled it No Use, which I’ve had since grad school. That, I feel certain about. More soon, I hope!

Lonely Crowds is out now.