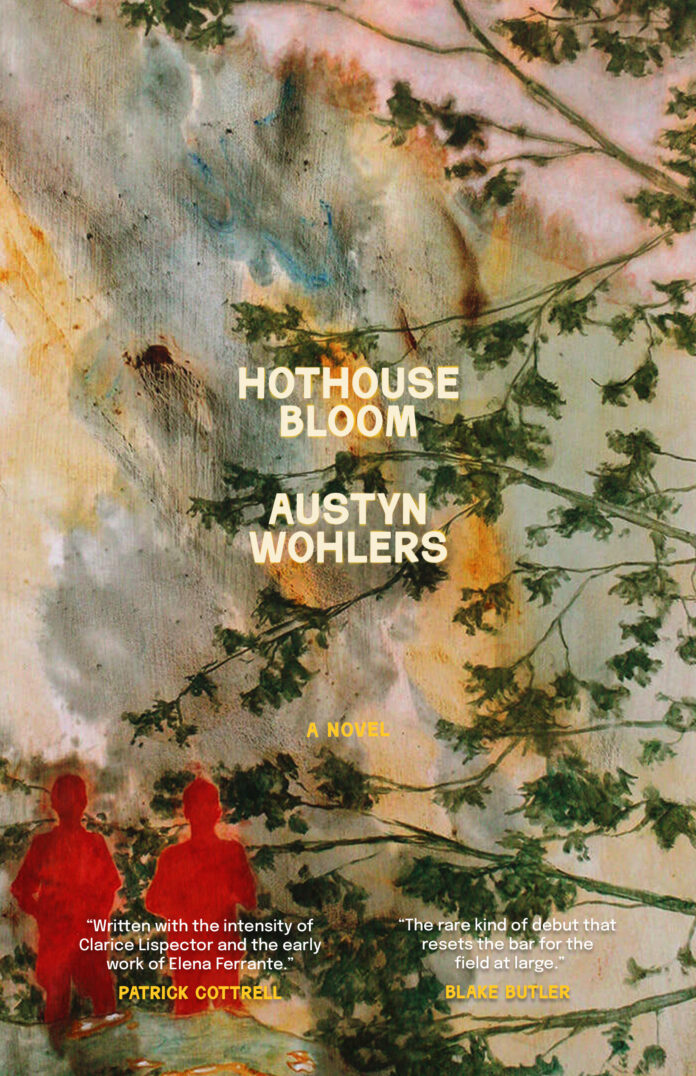

It’s fitting that my copy of Austyn Wohlers’ Hothouse Bloom showed up at my doorstep sopping wet, dripping with the rain of a recent thunderstorm. The debut novel, where a young woman leaves a city and her painting career after an undetailed event to care for her grandfather’s apple orchard, is uniquely concerned with the totality of nature. Anna not only wants to live in the orchard, but become it; she hopes to graft her consciousness onto the “ancient, colossal being” of the land. When a neighbor laments the repetition of upkeep tasks (weeding, watering, etc.), Anna says that’s what she’s after — “a certain absolute stillness of psyche, branches like extensions of her fingers, roots like blood vessels. To build up a world from a few repeated actions.”

These cosmic ideas take a while to emerge — from its first 30 or so pages, you’d get the wrong idea about what Hothouse Bloom is about. A sad girl tries to find herself via soft sentences about the enormity of nature and art. But thankfully, the novel is a grower. Anna studies the orchard but realizes it’s better to be in nature, hair in the dirt and the leaves. She marvels at the stars in the sky and often cries from happiness, passing the time by working with the earth in her hands. “Whenever a breeze reached her she felt her body reduce itself to something purely organic,” Wohlers writes. Suddenly the old world, with its beautiful books and meaningful conversations, pale in comparison to the feeling of lying between trees for hours.

She wishes to share this secret, that of “the submission to something outside the bounds of time,” and somewhat delusionally invites an old friend, Jan, to come stay and help out when the time comes. He’s a man who showed her “how to take yourself seriously as an artist even when faced with the vast nothing,” and feels she ought to repay the favor by broadening his consciousness. Anna is lonely; she has two bridges to the outside world, her dogs Midge and Pell, but they don’t talk back, after all. Neither do the trees.

Initially his presence is bothersome; when he steps on the land, Anna feels it on her own face. Living alone for weeks has heightened her mind, truly connecting her to the roots of agriculture, bringing her back to a more pure way of living, even if her thoughts have taken on the cadence of someone whose recent camping trip redefines their personality. Jan’s passions (he’s writing a book about a painter) seem flimsy in comparison to her earthy, muscling work. “Even better than making something is living something,” she tells him, guru-like.

But her pretentiousness is not without reason. Even though Jan interprets her brisk exit from art as a failure or an abrupt change in perspective, she’s realized that her goal — to “understand and process the world without language” — can be achieved far more easily here than in a cramped apartment with some paintbrushes. When he tells her to write this thought down, it’s clear he just doesn’t get it. Writing that, or anything down, would dilute the point. Words can’t capture what she feels. Anna doesn’t exist for art any more, but for her body that’s melting into the orchard. At one point, she chastises herself for not treating people like how she treats apples — that being with kindness. “Jan knows nothing of the inhuman anonymity with which I’m living,” she thinks. “How deliberately I’m annihilating.”

But something more insidious sneaks up on Anna — profit. The apples are starting to bloom, and now she needs workers to help her manage. She hires a meek boy and an experienced farmhand after placing an advertisement in the paper, along with a pomologist that diagnoses her apples’ new infections. In Anna’s “Index of Ruin,” Wohlers writes gracefully of nature’s wrath: “two sleek wasps” make an apple into “their cave”; another with “brown bumps with black pinpricks in their center like a swollen wound”; one rotted black has “gray warping concentric circles.” The apples “[were] alive and wet with bugs and fungus… cognizant.” It’s okay, she reminds herself, throwing away bundles of fruit, “Not everything is about money. Some things are about love.”

But she doesn’t remember her own advice. She becomes a landlord, property owner, a boss, hardening into a personality type she fled. She penny-pinches and nags, mood made worse by a cider Jan starts making by cutting rot off unusable apples and mashing them. She’s humiliated at the farmer’s market by Pleasant Hill Orchard, a jolly competitor who has diversified their product line with apple butters, vinegars, fruit jams, delightfully branded tote bags. She advertises pathetically and imagines the whole thing as sabotage. A seller trots over to introduce herself; irritated that this blocks the view, Anna nearly tells her to fuck off. Anna-as-earth-mother would be terrified by Anna-as-merchant, but you gotta do what you gotta do. Enlightenment and breeze-soaked days are traded for nights staring at the computer, eyes burning with dollar-ridden spreadsheets.

Jan’s interiority irritates Anna; Anna’s escapism irks Jan. None of the apples are selling, and on top of it all, she has to pay her workers for their time; one of them’s being greedy by billing her for help with house construction (she begrudgingly gives it over). The outside world isn’t seeming too bad (an escape from her escape); she pretends like the orchard is a tucked-away reality, but you can hear the car noises and smell the cigarette smoke even amongst the trees, Jan notes. It might not be too special after all. “There was life all around Anna trying to get in and it was like she didn’t know what to do with it,” he thinks.

Wohlers spears capitalism with, thankfully, not too much force, her character study astute and sharp. Anna turns exploitative just as the apples turn black with rot, inadequate care, or maybe, they pick up on the vibrations of her angst. Escape society only to be burdened by the demands of the marketplace — I’d be irritated too. Anna’s grief is familiar to anyone who has enjoyed a tech-free walk in nature while also itching for their phone. You’ll never see an apple the same way again after Hothouse Bloom — someone could have lost herself while picking it.

Hothouse Bloom is out now.