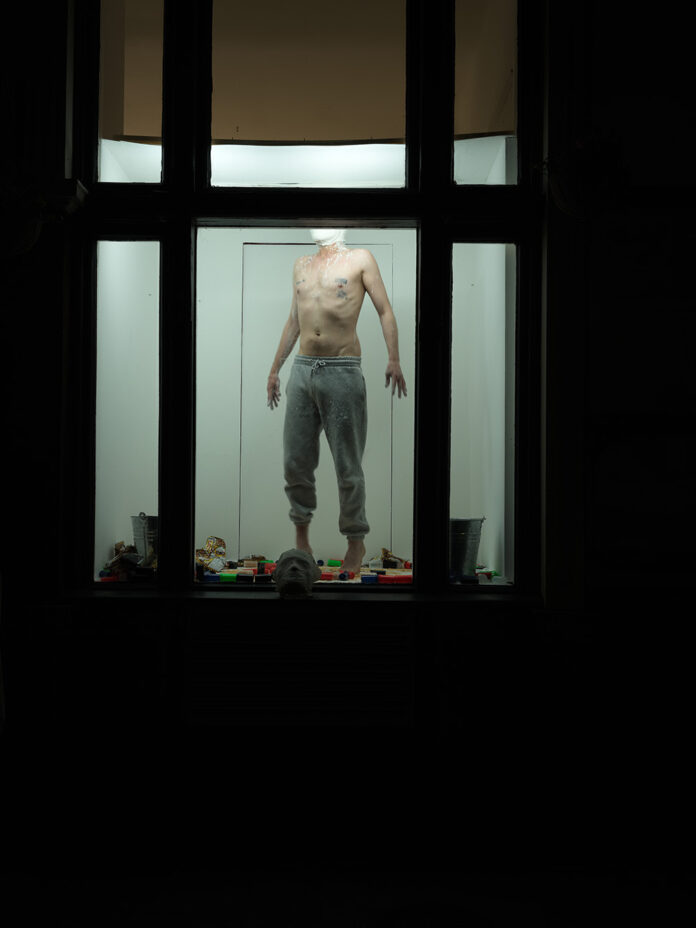

In Han Gao’s recent performance, I Tried to Be a Container, the body becomes both fragile architecture and resonant vessel. The work takes place within the charged transparency of a gallery window, where inside and outside collapse into one another. Gao begins alone, confined within the glass boundary, systematically breaking dry instant noodles. The gesture is careful, almost ritualistic, yet edged with violence. She then consumes the noodles, stuffing the fragments inside her t-shirt. The broken pieces are transmitted through the intimate channel of her body, eventually emerging from the legs of her yoga pants, to be collected and placed into small bottles. This process echoes both the abject intimacy of consumption and the destructive force of containment itself: to hold something, to process it, often requires that it first be broken and pass through the self.

Later, Gao leaves the interior to bring collaborator Sam into the space, trading places with him, shifting from the one who acts to the one who witnesses. This exchange destabilises the notion of fixed roles in performance: who is the container, and who is contained? The work resists simple resolution, dwelling instead in the tension between holding and being held, between the inside and the outside.

Sound plays a central role. The crunch of noodles, the rustle of fabric, and the physical effort of transmission transform into an unsettling texture, part brittle percussion, part crumbling architecture. These sonic fragments extend the performance beyond the visual, filling the air with the residue of destruction and intimate passage. The bottles, neatly arranged, become reliquaries of processed brokenness, small monuments to the impossibility of wholeness.

The piece is deeply situated in Gao’s ongoing investigation of trauma, memory, and the porousness of the self. To “be a container” is not only to enclose but also to be permeated, to risk shattering under pressure, and to transform what passes through. The act recalls feminist performance traditions where food, the abject, and the body intersect as sites of endurance and critique, while simultaneously carrying Gao’s own vocabulary of vulnerability and endurance.

The glass window, meanwhile, is both stage and metaphor. It reflects the city back onto the work, but never fully: as Gao notes, a window is not a mirror. It allows vision yet enforces separation. To watch from outside is to confront one’s own position in relation to the act of containment, to be implicated in the fragile economy of inside and out.

Ultimately, I Tried to Be a Container is not about offering closure but about staging fracture, displacement, and exchange. It leaves its audience suspended in the question of what it means to hold — a body, a memory, a breaking world — without breaking oneself.