The Antlers’ new album, Blight, widens the scope of Peter Silberman’s songwriting by reckoning with environmental catastrophe, taking cues from a range of science fiction media. But it begins in a homey place: the unsparing intimacy of Silberman’s voice, admitting to the ways he’s contributing to the destruction by simply going about his day, the way you might be when you first press play on the record: having a meal, ordering it. If you have mourned with the psychological devastation of 2009’s Hospice or 2011’s Burst Apart, it is disarming and powerful to hear his soulful whisper carrying the same weight in this conceptual framework. Though when Blight spirals toward a series of ambiguous apocalyptic events, it once again feels not conceptual but psychological, the sound of ecological anxiety – corrosive, wordless, outstretched – turning what could be a familiarly delicate (by the Antlers’ standards) listen into an eerily fragile one. “Will we be forgiven?” Silberman sings towards the end, accompanied by a faint keyboard as if the we is already out of the picture. “Should there come a great flood to drown out our decisions?”

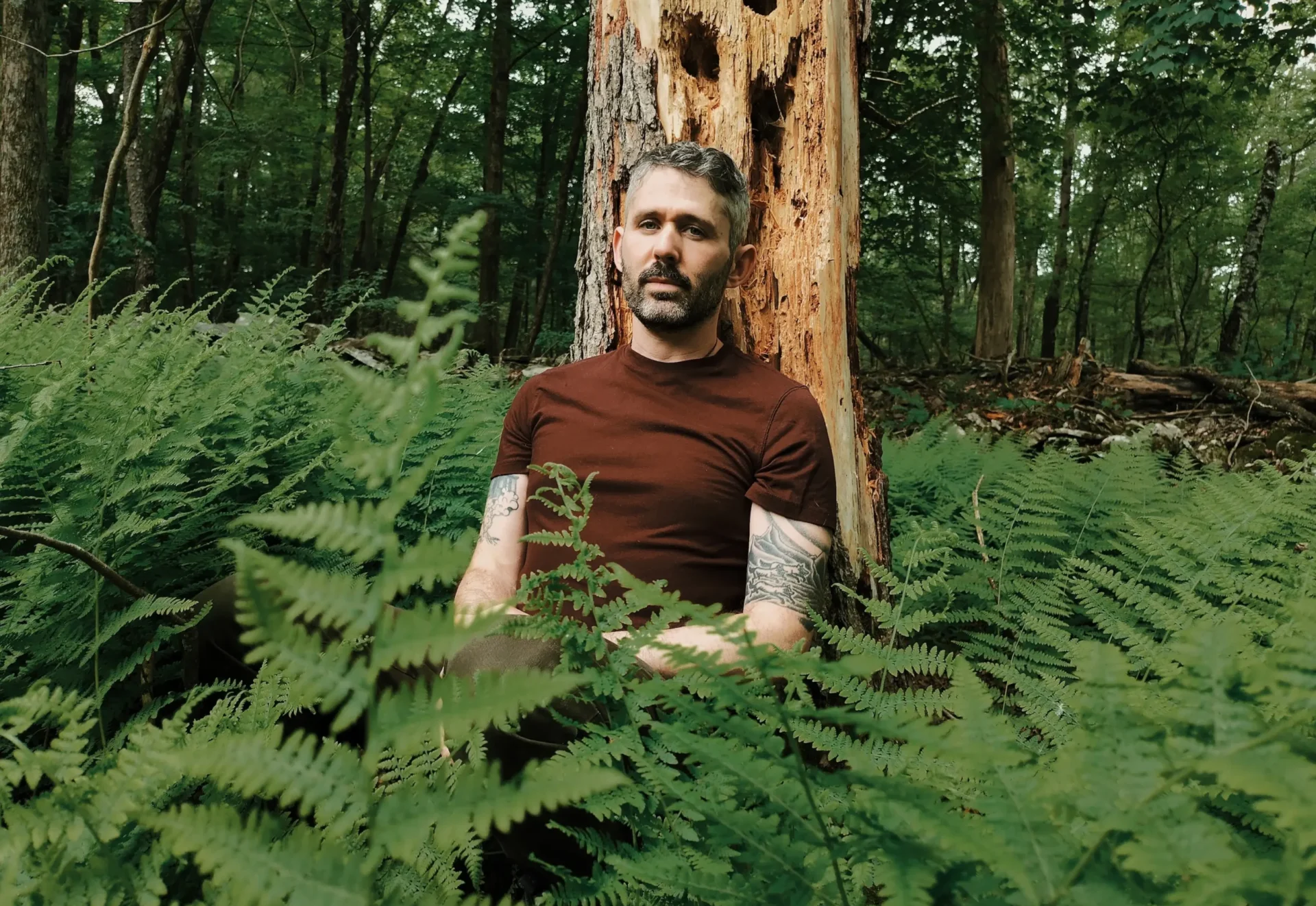

We caught up with the Antlers’ Peter Silberman to talk about The Leftovers, Arthur C. Clark, the Flaming Lips’ The Soft Bulletin, and other inspirations behind their new album Blight.

The TV show The Leftovers

There’s a few things about that show that influenced the record. The premise of the show, at least in the beginning, is that on just a random day, 2% of the world’s population vanishes into thin air. Everything kind of starts there, and it’s about the after-effects of that. It’s a show with a lot of ambiguity. They never really explain why that happened, what it meant, but there’s a lot of debate within the show about what it meant, why it happened, and how to proceed from there. There are a lot of spiritual and philosophical questions around that, the way that it affected people, the way it changed people. Musically, there’s some inspiration from The Leftovers. The score is this very beautiful piano theme that returns over and over again. I think at one point, I had learned it on piano, and then I started kind of riffing on it, and came up with these other short piano compositions that were inspired by that. ‘Something in the Air’ and the last track, ‘They Lost All of Us’, came out of that period.

But thematically, ‘Something in the Air’ being about a sudden disastrous event that catches everybody off guard, and it’s never really named, but it’s described, and the way that it’s described leaves ambiguity as to what actually happened. And then ‘Deactivate’ is essentially about a sort of an apocalyptic event, and a lot of the description that is in that song, about people suddenly disappearing and dogs running around without someone walking them – that’s really inspired by The Leftovers. It’s the first scene of the show, and they return to it a few different times, but showing this moment when suddenly people just disappeared, and suddenly cars are driving without drivers in them, and it’s a very powerful image. ‘Deactivate’ is more tied into AI and virtual worlds, uploading consciousness, things like that, which is not really what The Leftovers is about, but I think there’s some inspiration there. And then the last track on the record, ‘They Lost All of Us’, the title is actually from a monologue towards the end of the series that Carrie Coon delivers. It’s one of those monologues that is powerful because it’s somebody explaining something without the show showing it to you. And it forces you to use your imagination, but their description is so vivid that you see exactly what they’re talking about in your mind.

The Leftovers had a lot of questions of how to proceed with life after something so horrible, so disturbing, and philosophically confusing happens. How do we carry on? And that’s a lot of what this record ultimately gets to: How do we live with ourselves, knowing what we’re doing to the planet, the environment, and its creatures, and ultimately to ourselves?

It’s interesting that the show begins with this ambiguous, apocalyptic event, whereas in Blight it’s kind of in the middle. Was that an intentional decision?

I really felt like it was important to reach that gradually. In order for the point of the record to get across, it had to start from a really ordinary place of questioning your choices as just a person who’s shopping and eating and participating in society. That, to me, felt like that was a good way to really underline the central questions around the record, to not start off in a place of science fiction and imagination. Part of what I wanted to accomplish with the record was almost emulating the experience of spinning out about some of these questions. You know, you’ve thrown out a piece of plastic, and then you start wondering to yourself, what happens to it? Does it matter? Maybe it does matter, because it just sits there in a landfill, and what happens when millions and millions of people are throwing their plastic into a landfill, and it’s just sitting there, and what went into making this thing? There is this snowball effect going from, “Here’s what I did, here’s all the thoughts that I have about it, and here’s where my mind goes.” It goes to the most extremes eventually.

Twin Peaks: The Return Part 8

I think that episode does stand apart from the rest of the series, because it really almost felt like a film in itself. As a refresher, that’s the episode that – [laughs] well, a lot a lot happens in it, but it’s this long, almost like a Terrence Malik sequence, seeming like it’s going back to the genesis of the entire universe. I’m not even sure if it’s supposed to be the creation of the universe – it’s David Lynch, so it’s ambiguous – but what I took from it was that it was trying to trace back to the creation of the evil that permeates that whole world. There’s this long abstract sequence that culminates in the explosion of the first atomic bomb, one of the atomic tests in New Mexico. It comes as a surprise when it happens, after this long, slowly paced sequence of imaages where you’re not exactly sure where or when in time that you are, and some of it is much more visual and almost ambient. And then it culminates with this explosion, and the evil was seemingly born out of that.

‘Deactivate’ is where that episode made its way into the record. Specifically, the moment at the end of the track – there’s this dreamy transition where it sounds as if you’re ascending to heaven, and it’s very pretty, skittery electronics and looping vocals. It sounds like this blissful arrival, and it’s followed by this sound of doom.

This rumbling.

Yeah. It sounds weirdly digital – it doesn’t sound like an explosion exactly, it sounds like something else, and there’s a click that happens that kind of changes the whole texture of the sound. I think in creating that sound, I was thinking of that atomic explosion in Twin Peaks, but I didn’t want it to sound like an explosion, I wanted it to sound like something we’ve never heard of before. A kind of extinction event that is entirely new – in the context of the record, it might be about consciousness being uploaded, and then that being shut off, and what that sounds like.

How did you get to that sound?

It was intensely compressed synth manipulation that was fed through a bunch of hardware to give it this unusual quality – this deep, not a tone exactly, but a noise, that is then subject to whatever glitches and sonic abnormalities happen when you’re slamming something with compression, and the noise floor rises because of however the gate is working. It’s a little technical, but it’s essentially trying to create the sound I was hearing in my head using a synth and a compressor and a couple other things.

Childhood’s End and 2001: A Space Odyssey by Arthur C. Clark

The premise of Childhood’s End book is that an advanced alien race comes to Earth and takes control of Earth in a benevolent way. The book was written in the ‘50s, so it’s very Cold War, nuclear arms race-coded, but the alien race is saying, “Humanity, you are on the verge of wiping each other out, so we’re gonna take control here, and we’re gonna run the show to keep you from killing yourselves, and this is all so that we can help you survive to the next era of your existence.” And then a bunch of other stuff happens, and it’s not quite as benevolent.

I think this idea of a world on the edge, and a world that’s kind of not aware of how close to the brink it is, was something I was thinking about a lot while working on the record. In ‘Deactivate’, there is this sort of intelligence that comes and says, “We’re going to we’re gonna lift you out of this mess,” except, in the case of ‘Deactivate’, it’s an artificial intelligence. It gives the impression of being benevolent and looking out for our best interests, but halfway through the song, there’s a doubled voice that comes in, which is this other intelligence, and I wrote it to sound like a sales pitch. It’s like a startup pitching you on their great new technology.

“Eternity in betaware.”

Yeah, exactly. And then what follows is that doom sound at the end, which kind of speaks for itself. Pulling a bit of that premise from Childhood’s End, and then 2001 as well. That transition sequence in ‘Deactivate’ was sort of my version of the Stargate sequence in 2001. It didn’t turn out exactly as I was imagining it to, because I think that’s what happens: You have an idea in your head, and then you work on it and it turns into something slightly different.

Part of what drew me to the lyricism in ‘Deactivate’ is the irony of how this intelligence betrays the risks of what it’s pitching – “losing your treasury of memory, your tendency for reverie,” these indisposable things it would know nothing about.

That’s how it feels, sometimes, when you see pitches of companies or different AI models that are talking about all the ways they’re going to make life easier for you, and if you’re a person that appreciates analog life, work, and creaticity at all, it can feel like they’re saying to you, “Don’t waste your time expressing yourself. That takes up too much of your day. What you want to be doing is nothing, and have somebody else creating for you, and somebody else thinking for you.” So yeah, there is an irony in there that almost feels like they don’t realize what they’re saying.

The Cake Tree in the Ruins by Akiyuki Nosaka

He wasn’t an author I was familiar with. I was given the book as a gift by my mother-in-law, and it just broke my heart right away. Every story is really emotionally hard to read, but they’re written almost like they’re children’s stories. They all revolve around this period, basically in post-World War II Japan. But the very end of the war, and in some cases, where the news had not yet reached Japan that the war was over. A lot of it takes place in the wreckage of different villages and cities, and it’s talking a lot about this post-apocalyptic landscape and the people and the animals in it. All the innocence, basically. It’s very visceral, and it’s graphic, and it’s things that are hard to face about the cost of war, a lot of the collateral damage around it. The way that it was written was so moving, it really didn’t sugarcoat anything. It’s very direct in a lot of ways, and it had a really strong effect on me when I was reading it. I think that really made its way into songs like ‘Carnage’ and ‘Calamity’, really just facing these things head on.

When did you consider this unflinching portrayal of non-human suffering to be an important part of the album? What was your thinking around the language you were going to use?

Pretty soon into the process, it felt like the only way to talk about this stuff in a way that was maybe going to actually reach people was to be very direct and graphic and detailed about it. I think that there are a lot of phrases and terminology around these issues that we’ve almost gotten too used to hearing. Even the words “climate change,” at least in this country, it’s a very divisive term, and probably half the country dismisses it as not a real thing. For the other half, we’re also not exactly even sure what we’re talking about when we’re talking about climate change. And same goes with pollution, same goes with even consumerism, which is a word that I’ve been kind of reluctant to use in talking about this record, but it’s the one I keep coming back to. It’s almost like jargon.

I felt like for the sake of the message of this record and what I was trying to get across with these songs, the details were what was going to make the difference, because they create an image that you then see in your mind and can be hard to shake. ‘Carnage’ is talking about these different instances of accidental animal cruelty, and for me, when I had seen some of that, I can’t erase the image from my mind. And it changes the way I think about the creatures I’m sharing space with. As opposed to more general ideas about, you know, animals losing habitats – you can say something about that, and it’s almost a little too vague. But I think getting into the specifics and the details is what has more of an effect. I think that goes for the environment, for pollution and contamination, too. You can present a lot of data about things like contamination, but if you can point to details of something anecdotal, it’s the kind of thing that sticks with you and maybe creates a lasting feeling of urgency about the problem.

It also raises the question of, where do you draw the line between incidental and intentional? If you create an image in your mind, is there a degree of separation that makes it less impactful than seeing the damage in front og you? I’m curious if thinking about these questions in the context of the record had a palpable effect in your life outside of it.

I think it solidified a growing awareness that I had been developing over the last several years, a growing sensitivity to a lot of these issues, other living creatures, the environment, and my own impact on it. I think that had been growing already. This record was an expression of that change in my own consciousness about it. Once the record was finished, I don’t think it answered any questions for me, but it solidified it as sort of the torch that I was gonna carry for a little while now. Because now I’m gonna go out and I’m gonna talk about it, and I’m gonna stand behind this work and the message of the work, and it makes it so that there’s no shying away from it.

I’m cautious in asking, because a lot of artists would like to make a record like Blight and not necessarily want to carry that torch.

I’m a bit nervous to do it. I’m doing my best to do my research so that I can talk about this stuff articulately. The record is a commitment to doing something about it, because I think I came out of it, and part of the record is about this, like, “Can I do anything, or is everything hopeless?” I still don’t really know the answer to the question, but I think putting the record out there and talking about it is a first step for me.

The World-Ending Fire by Wendell Berry

This book does seem like maybe one bit of research, a tool for articulating some of these ideas.

I’m actually still reading that collection and have been for a couple years. I’m moving through it slowly. It’s a collection of essays, so it’s not necessarily about one thing, but I think what made its way into the record is Wendell Berry talking about local ecosystems. The way that they change over time, the way that they are either degraded or restored over generations experiencing the history of a place in its woods, in its wildlife corridors, in the quality of the soil. He gets very down into the weeds with it, but he talks about soil health, he’s talking about decisions that farmers or developers made 100 years ago that are still impacting the health of the land. I don’t know that we always think about those things, but there’s this record that exists in the places where we live that is also continuing to be written. The simplest way of putting it is: The decisions that are made now, and the decisions that were made a long time ago, continue to affect things now and into the future. Ultimately the point being what goes around comes around, and these choices will come back to haunt us eventually – if they haven’t already.

The song ‘Pour’ feels like a direct expression of that.

Yeah, I think that that song came out of reading him and getting to know a local environment, and living there long enough to watch it change, to see the cumulative effects of the sort of ordinary things that happen there: cutting down patches of forest, or in the case of the ‘Pour’, this repeated dumping of chemicals. How that affects the groundwater, the drinking water, and the people who live in this neighborhood who don’t even realize this is happening.

I know you recorded most of the record in your home studio in upstate New York. How would you describe the changes to your environment that you’re witnessing every day, but also over a period of years?

My wife and I have been living in this house we’re in now for a little over five years, which is a good amount of time to be in a place to get to know it and to watch it change. It’s a really beautiful area, and I feel like I’ve really gotten to know the land really well. The biggest change I’ve noticed is patches of forest behind the house on a neighboring property being cut down. It’s an ongoing project that’s been happening for a long time. There’s a farmer who lives up the hill from us who owns all of that land, and he’s been cutting down these woods and making a road through the woods for his vehicles to get through to the hayfields. It’s complicated, I guess. On the very basic level, I feel a sense of ownership over this land, and it’s not mine. But I feel this connection to it, having spent so much time in it, and I have to remind myself that it’s his. But that also flies in the face of, you know, you can’t really own the land. Nobody owns the land, but in this society, we have a system in place to allow us to believe that we own the environment.

I get attached to the present state of things, and to see so much forest get cut down to build a road, just as an example – as you develop awareness of how ecosystems work, your awareness shifts from the bigger creatures that are displaced, which are sort of easy to have feelings toward, but there’s so much more life happening in a forest. To even become sensitive to insect life, plant life, these things that we often think of as, “Well, you can’t move through life trying to not step on every ant that you see.” But I find myself asking, why not? Doesn’t mean that I abide by that, because it’s impossible, and every step you take, something is beneath your feet, at least if you’re walking on grass or walking in the woods. People can’t help but have some kind of destructive impact, I guess. But for me, it’s hard to see all that happening and not think about the death, the displacement and the destruction, the way that it’s disrupting the ecosystem.

But then I also remind myself that every road was built this way. Every road was built by knocking something down to make way for it, and that’s part of how our society has come to exist, and how I am even here able to appreciate nature, is that a road brought me here, and that road came about from some kind of deforestation. I don’t know what to do with that all the time. There’s this inclination, I think, to be like, “Let’s stop all the development now, let’s stop all the deforestation now, we have enough.” And I’d like to believe that’s true, but I don’t think it really works that way. I guess there are trade-offs that are made, like clearing land to put up solar panels or windmills. Some people would argue it’s not worth the cost, ut if it’s for the sake of renewable energy, then maybe it is. I don’t know. I wish I had some answers. [laughs] But this is the human contradiction: How do we survive without destroying what we depend on?

The Soft Bulletin by The Flaming Lips

What made you go back to that record?

That record has been one of my favorite records since I was a teenager. I probably first heard it 25 years ago, and I’ve never really found anything like it, even though I think there’s lots of records that were influenced by and borrowed from it. Sonically, I think it’s the fullest expression of something. I think it’s really adventurous and unusual. The combination of these smashed drums and sweeping orchestras and almost nothing in between – there is other instrumentation, there is a band there, but it really is focusing on these two major elements, the instrumentation is shifting throughout the whole record. I think that that fed into Blight a lot. Stylistically, it’s changing throughout the course of it, and aesthetically it’s changing. I think there’s something in that record that doesn’t feel calculated. The experiments are not precious – they’re fun sonic experiments, full of weird glitchiness, rough around the edges, and kind of messy. It’s been an influence for me for a long time, but I don’t always let the extremes of that in, the feelings of something that is distorted to the point where it feels like it’s maybe falling apart or degraded.

That record also has a sequence that makes a lot of sense in an intuitive way. You’re not necessarily following along with a story that is threaded throughout, but there is a trajectory the whole time, and it does feel like it’s touching on both the small and bigger philosophical questions. It’s just a record with a ton of heart.

In general, what is your relationship now to many of these formative indie rock records? How often do you revisit them?

It depends, and sometimes it depends on what I’m working on. For this record, I did find myself returning to a lot of these records that I listened to a lot in high school that were foundational records for me when I first started making my own records. Things that I aspired to, or just things that blew my mind open at the time. At that time in my life, it was so exciting to have norms be challenged. When I was growing up, there was something comforting about hearing people making unexpected music, music that broke norms but wasn’t so abstract that it was difficult. That sort of gateway effect of: Here’s songs that you can grab onto, but they’re presented in an unusual way. It requires. a bit of participation from you to to really sink your teeth into them and to understand them. The Soft Bulletin was one of those for me, and so was Yoshimi, and Kid A and Amnesiac and OK Computer. I could understand them, but they were nothing I’d ever heard before, and they made a lot of other music that I had been listening to up until that point feel extremely normal by comparison, and not that interesting. It just changed my notions of what was possible.

Double Negative by Low

That record evokes a tech-doomed dystopia, but in this really ambient, uneasy way. It was abstract, but a lot of people attached this feeling to it.

I remember when I first heard it and then continued listening to it and getting to know it, it sounded and felt like the current moment. Even if it wasn’t overtly speaking about it, it just had a texture to it, an attitude and a disposition that felt dystopian, the way that it feels to be alive and aware of the world right now. This confused, disoriented, doom-ridden panic. And that’s coupled with the production style, which is extremely compressed and disorienting and sounds strange. Those extremes are, I think, what makes it powerful.

I went into Blight really wanting to carry that torch. It didn’t happen in the same way. I thought I was expecting to make something as blown out and as chopped-up, and ultimately I made a record that sounds more like me than them, but I was very inspired by it. They’ve been one of my favorite bands for a very long time, and I loved how they would make records that sounded very homey and warm, and then the next record, like Drums and Guns, would be so strange and current and relevant and kind of scary. And then the next record might be another sweet record, another kind record, and then the one after that will be a totally different kind of left turn. They always kept you guessing, and it was always good. Double Negative was one of those that makes you excited to make your own record, to conduct your own experiments, and to lean into that darkness and see what comes out of it.

BJ Burton’s production is a foundational part of that record, and I hear the influence of that kind of vocal processing on Blight’s title track and ‘Pour’.

Yeah, definitely. I started doing some vocal processing on this series of singles that I made before Blight, and I carried that into this record. I thought this was gonna end up being a more heavily vocally processed record, and I ended up just choosing to do it in a handful of moments, using a harmonizer where you’re basically creating harmonies of your own voice, but you’re playing them on the keyboard. They’re MIDI MIDI-controlled harmonies, which is a process I learned about from working on this Wild Pink record a few years ago, because he was doing that with a lot of his songs as a kind of drop shadow against his vocals. It was something I had heard before, but I didn’t know how people did it, and he explained it to me. Then I got my own gear, and I started doing it.

It’s that, plus passing them through lots of lots of hardware and filters and things like that. To me, they ended up being used symbolically on the record to represent the duality of having a digital virtual self running alongside your actual self, and how that is becoming increasingly the way things are for most of us. We don’t know what that will look like in the future, and if one will come to dominate the other, this sort of facsimile of ourselves that is somewhere living in the uncanny valley. But I ultimately decided that I didn’t want the entire record to utilize that, because there needed to be some contrast between the human and the hybrid.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

The Antlers’ Blight is out October 10 via Transgressive Records.