Language does not die in the work of Xinyue Liang; it deteriorates. It diminishes, slowly, like a hill after rain. The works, seen recently in exhibitions in London, Paris and Milan, are not statements but sediments: for objects that seem to conserve something that speech has long since abandoned. The surfaces of her sculptural fragments are at the first glance, phallic, raw, and weary, like things from the strata of a long utterance; but under that quiescence something quivers.

Liang was born in Henan in 1998, and her evolution began with Chinese calligraphy, a discipline which brings trend, reiteration and veneration. From her undergraduate instruction in the calligraphic traditions of China at Qiongtai Normal University, she gained an early vocabulary of gesture, not measurable only in printed word and line, but by breath and silence. Afterwards, and at Camberwell College of Arts in London, that vocabulary ferments. Calligraphy is no longer writing, it is substance. The brush is used by her no longer to write meaning, but to explain it.

Liang’s work to-day vibrates between drawing, collage, installation, and pottery, but all her pieces of work suffer from that fundamental interrogation, how is it possible for tradition to exist when the medium, one of which traditionally is so much to give its life, begins to decay, she pursues to-day the problem in her opening work Fragility of mud by Porcelain and Paper Versions, this question being put by her in the logic of material of mud and of Dai paper and establishing in the confusion its experiment with the earthly nature and with the textural.

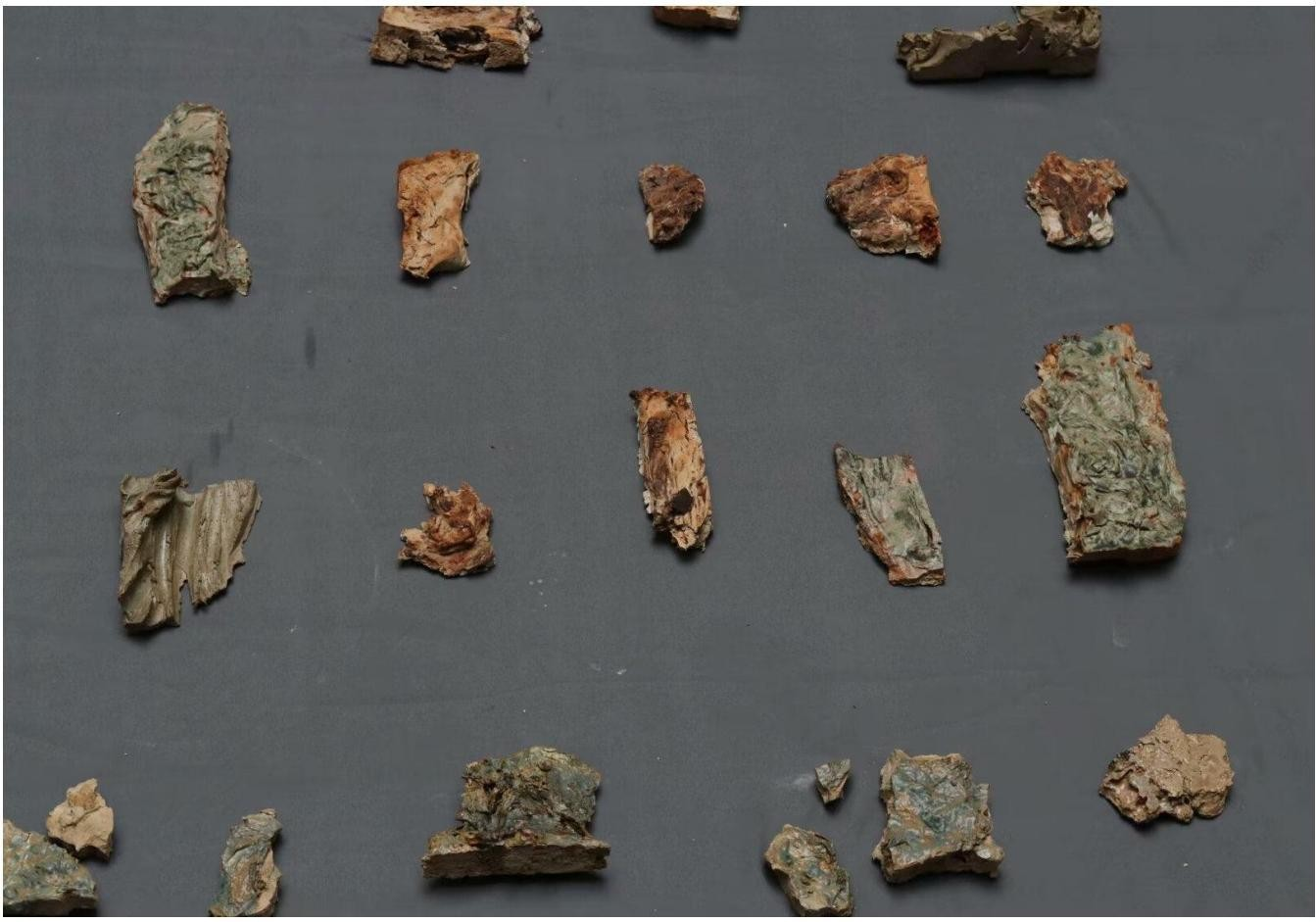

In the centre of this project is another of her uses of Dai paper, an eight-hundred-year-old Yunnanese tradition in the manufacture of paper from the bark of native trees. The paper, which was formerly used in the production of sacred books, is here torn, pulped and mixed with clay, so that its fibrous structure forms a unique tactile field of decay. Liang mixes this pulp with mud of different natures and dries it in sheets and fragments which buckle and crack. Immediately before they set, in the other, she writes on them with the colours of the ancient scripts, such as oracle-bone symbols, pictography and symbols in cuneiform, the result of her appearance being less recognisable texts than fossilised appearances. What remains is not the speech of language, but its evocation.

The use of writing is in these pieces neither mere consumption nor decoration; it is entropy : the clay absorbs the colour, the colour decays and again the once-holy link becomes a gesture. Liang translates the language of condensing into sediment and sediment into language. In this slow alchemical she is rendering a particular contemporary fear, the loss of continuance produced by the quick slavering enumeration of cultures, which is produced quicker than it can be received.

The installation of Fragility of Mud accentuates this temporal uncertainty. Fragments are splattered among masses, where the forms re-echo both archaeological relics and geological samples. Each piece is without hierarchy, there is no, or no especially apparent, centre, merely a constellation of gestures. The eye of the spectator wanders over the field and is ever again coming to the collapse of one or another fragment, and never to the end. The installation reads less like an object of art than like an after-thought.

What is remarkable in Liang’s work is what is one of her duals of appearance, and what might perhaps be in a sense called her refusal of repair. The cracks and niches of it are not metaphorically but really cases of frailty in the very essence, they are the way. She permits the matter to collapse, dry unevenly, break, crumble. This conscious state of behaving gives her works a paradoxically evidentiary virtue. By permitting decay to partake frequently in creation, Liang succeeds in exploding the ordinary idea of the word “Removed,” which she inherits equally from pottery and lettering.

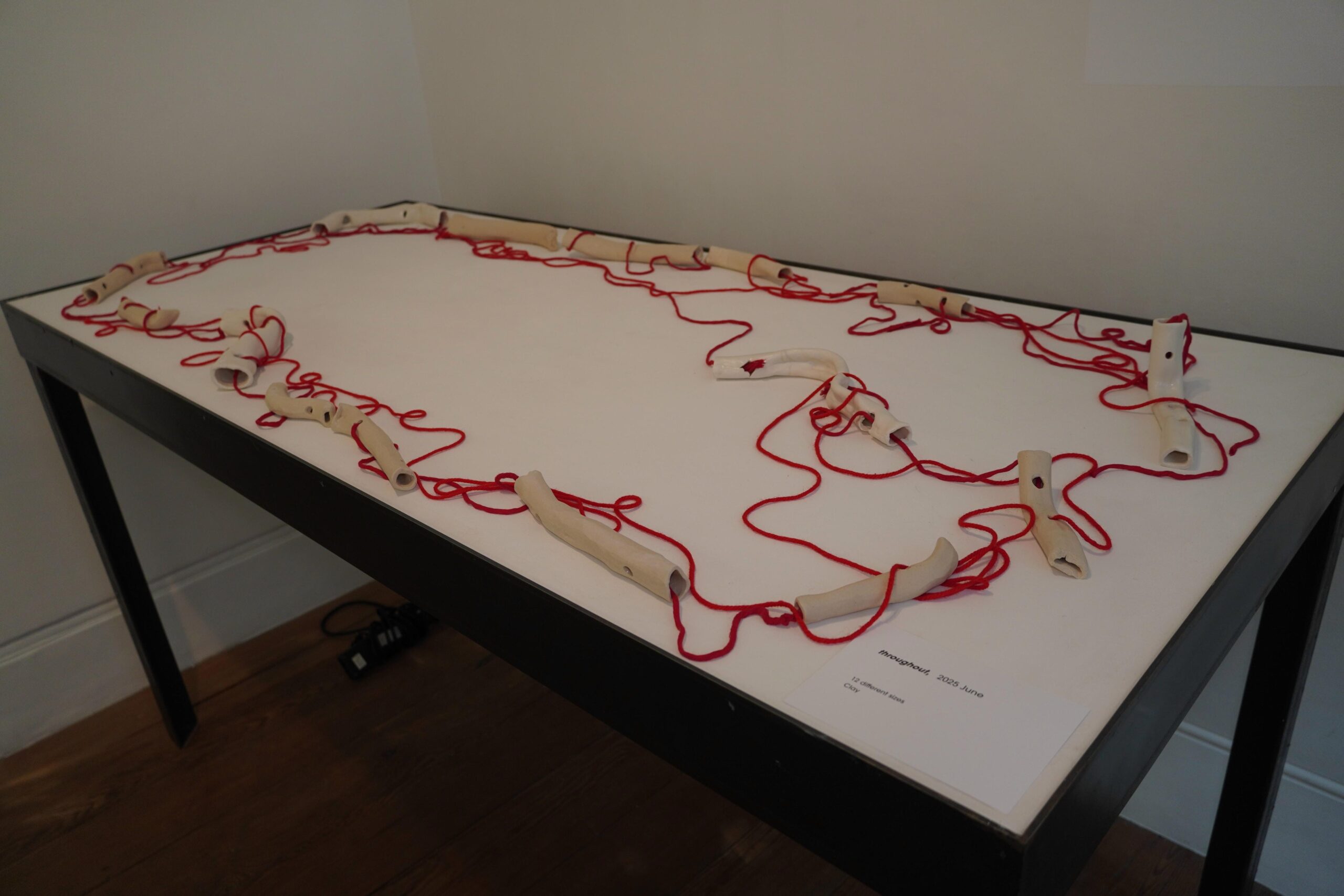

The later series of Plantation, begins to treat the language-ment circumstances in a broad capsule. Here the light and the Dai paper are attained to merge by contact into Vessellite forms, objects which nevertheless are curiously inherited ideas of the word “Utensil.” The syntax of the skeleton is utility, yet there is no utility in their utilitarian guise. The surfaces are marked by white blots — pauses of feeling, moments of unhymned form that interrupt the stage of order. The Dubium is not continent in voice, but there are no vessels but continuities, areas wherein is fluidity, potentiality and air. Called “relations” they are performed culpably by archipelagic architecture, openly, porous, incomplete.

To engage with these vessels is to grapple with the idea of waiting. Each is suspended in an indeterminate space between utility and meaning, its smooth paleness evoking both bone and skin. They seem to anticipate a destiny of inscription which is elusive. The blank spaces of Liang’s work are temporal voids, instances where an ancient tradition pauses to inhale and exhale. The incompleteness so fundamental to her aesthetic is resistant to the Western fetish for the finished object. And it is this conditioning that she insists upon, situating her work in a liminal field of becoming.

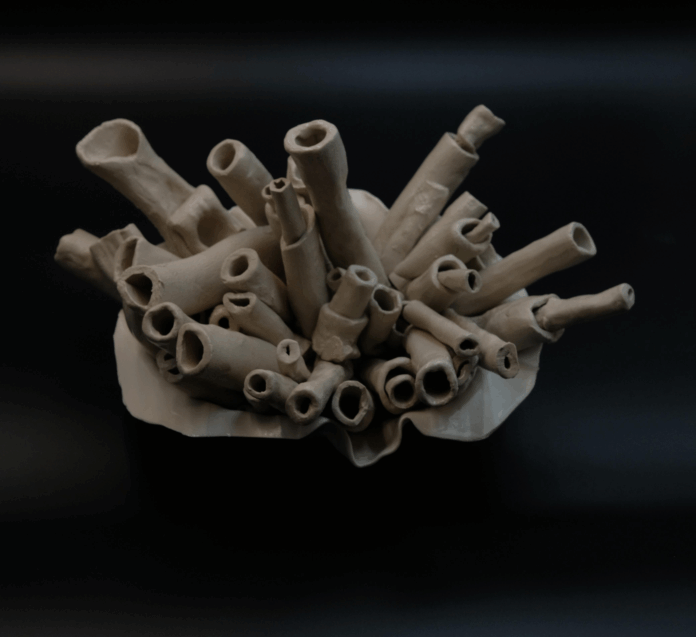

Liang’s engagement with the “failure” of the verbal is most apparent in the tubes of porcelain form. These porous, organic shapes speak of coral skeletons and wind-instruments, hollow things. Every tube carries small perforations, suggestive of breath residue. The writing in these works becomes hearing, or more accurately, the moment preceding hearing. Voices may have once been carried in these forms, but it is silence they now echo.

The dialectic of calligraphy and clay, gesture and gravity, runs through the works of Liang. Calligraphy lives traditionally in the two-dimensional configuration of surface, bestowing on the trace of hand and flow of meaning its priority. Clay, on the contrary, refuses the planar, coursing as mass, as resistance. By forcing into conflict these two material logics, Liang creates a surface pregnant with tension which requires thought to adapt to tactility. Her works thus occupy a philosophical category analogous to Derrida’s notion of différance: meaning is deferred, displaced, always inchoate.

Culturally considered, Liang’s oeuvre can be framed as an investigation into the ethics of inheritance. The problem presented, namely, how to sustain tradition without mummifying it, recapitulates the problem of many contemporary Chinese artists walking the line between heritage and modernity. In contrast to those artists who monumentalize history by repetition, Liang confronts history through disintegration. Her works do not translate Chinese sculpture into modern terms; they allow it to erode, to collapse with alien materials to the point that it is unrecognizable though still living.

There is a tendency to describe Liang’s art as post-traditional, but such a description would miss the point. Her works are not “after” tradition, they are in it, trapped in its process of evolution. The Dai paper, ancient but also frail, is the embodiment of this paradox. It functions in effect as medium and metaphor, being at once an archive of handwork and a witness to decay. Bulking the Dai paper is mud, a medium equivalent to both origin and decay, and the result is a conversation between survival and dissolution.

In formal terms Liang’s surfaces have the feel of geological time rather than artistic gesture. Their cracks and fissures recall earthquakes; their pigments mineral oxidations. Underlying the earthy associations, however, is an intense conceptual discipline. Every mark is calculated to appear accidental, every imperfection choreographed to resist polish. It is this fine balance between mastery and the relinquishing of mastery, that places her work in the same relationship as that of Anselm Kiefer’s material melancholia and Yeesookyung’s fractured porcelain assemblages, but Liang is left by the way side with her finely wrought sensitivity, in that it is less monumental; more meditative.

It seems that she must possess an unnerving confidence in the nature of uncertainty as an artist with reference to such exhibitions as: Bound & Beyond, Fluid Horizons, Everything Then is Now. But the installation of these is not with a view to a contending with weighty dimension, but a friendly invitation for duration in the pursuit of, what? Tracing surfaces, reading textures, feeling the unsensible. Liang subverts the privileged viewer mentality into that of. Now unlearn those wonderful habits of interpreting that you possess and settle down into a position of observing.

This requires patience. This practice does not exhaust itself in divulging, but in a process of sedimentation. The more one observes the more is perceived the delicate manipulation between writing and weathering. The lines scored into her clay resemble language, but open themselves in such a way that, before sense can take root, unknowing arrives instead, quietly, almost joyfully. The viewer is left not with comprehension, but with a fine dust of recognition suspended in thought.

In this way Liang’s work re-defines fragility not as weakness but as continuity. The fissures are not wounds, but orifices. The decayed surface becomes the one condition of permanence. The past is not preserved but enabled to modify, to breathe, to produce its peculiar grace of decay. In a world of worship and servility, an altar to permanence, Liang’s work throws by its function of the things past into a state of anachronism, the absence is a measure of its evil.

As the mud dries and the inscriptions fade is a reminder on the transitory nature of culture. Which survives by forgetting. What is of the essence, is not the piece so much as the echo of it, not so much the vessel, as the atmosphere in which dwelt that which it contained. Liang’s practice teaches us as is appropriate, to read the silence between ourselves and materials, the void in which meaning slackens its hold and matter is the entity that evangelises its own intelligence.