At the beginning of this summer, some friends and I took a beach trip to Charleston, South Carolina, where one night we went to a bar that simultaneously hosted a wedding afterparty and was partially walled off to anyone not invited. We squeezed in between southerners and the man I was sitting next to started flirting with my friend, who promptly asked who he voted for. “Donald J. Trump,” he replied, and my friend immediately started arguing with him. He turned to me, and I said, “I’m sorry, I don’t really want to talk to you.” He went back to arguing.

I said what I said mostly because I wanted my night to go a certain way, and my plan didn’t involve arguing about politics (unless my friends wanted to). I was having a good time, and I wanted to talk to people from Charleston who I’d get along with, like a different man next to me in a Kacey Musgraves shirt who was quizzing me about Bon Iver and Saya Gray. But I didn’t mean I never wanted to talk to the Trump voter — I feared that by shutting him down completely, I played into his stereotypes of an opponent: close-minded, only wanting to stay in my information bubble. Plus, I can admit it was sort of rude to literally turn in my seat so that he couldn’t speak to me. I had severed this line of communication and widened the gap between our politics by refusing to engage in a conversation that had a (minor) possibility of understanding each other. But then again, he and my friend argued for a long time after that, and neither of them, I could tell, changed each other’s minds.

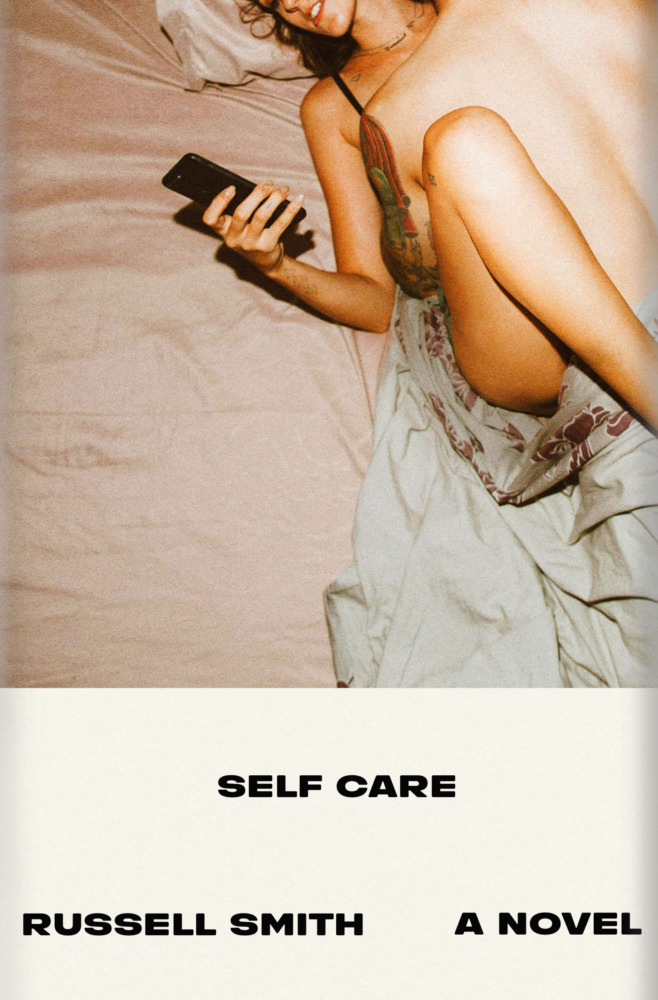

Should you befriend a Nazi? That’s at the question of Russell Smith’s provocative new novel, Self Care, where a digital writer named Gloria chats with a boy she sees at an anti-immigration rally under the guise of an interview for her column. Not to say that the Trump supporter I talked to was a Nazi, but Gloria’s Daryn might be — he’s with his misogynist buddies, wearing a badge that signifies his involvement within the movement. Gloria is convinced: this dude hates women. “That’s not what it means,” Daryn pleads, “That’s not what it’s about. We respect women.”

Despite their conversations, and the fact that they eventually have sex, Gloria is cynical that he isn’t, deep down, a bad person. He’s lurking on the forums and complains that women don’t pay him any attention: “If you have a small dick like me,” he’s written, “you are just never going to be confident enough to be able to approach a girl, which is hilarious, because you know she can’t see it, but you’re always aware of it.” Who knows if this is the product of intense manosphere podcasts or a debilitating self-esteem, but Gloria is curious about where these ideas started. She’s not without her knee-jerk reactions: she calls him a loser when he calls her beautiful. Their conversations are an exercise in excising a deep hurt in the heart of the contemporary man, and often radiate with an intense honesty. After a while, Gloria enjoys spending time with him, abandoning her article. She antagonizes him, teases that if he gets a girlfriend he’ll be kicked out of his misogyny group.

Even more curious is how he submits to Gloria when they’re having sex — he does what he’s told and he likes it that way, but refuses to talk about why that might be the case, lest his masculinity gets called into question. On top of that, it’s a far cry from what he’s posted online: “We are naturally dominant, and so it’s unnatural that women should be artificially given so much power over us and unnatural that we have to feminize our values and the values of the whole society.” What would the misogynists think if they knew one of their own was getting tied up and ordered around?

I’ve often wondered what pushes extremists towards their breaking point, at what time the fracturing of contemporary thought becomes such that we are pushed to hate women, hate men, hate minorities, murder people we don’t agree with. Self Care doesn’t have the answer, but at least it engages in a (yes, fictitious) dialogue with one of these men. Daryn is a person as well as a possible woman-hater. Smith says getting to know both of these separate personalities to see what’s underneath might be worth a shot.

Self Care is out now.