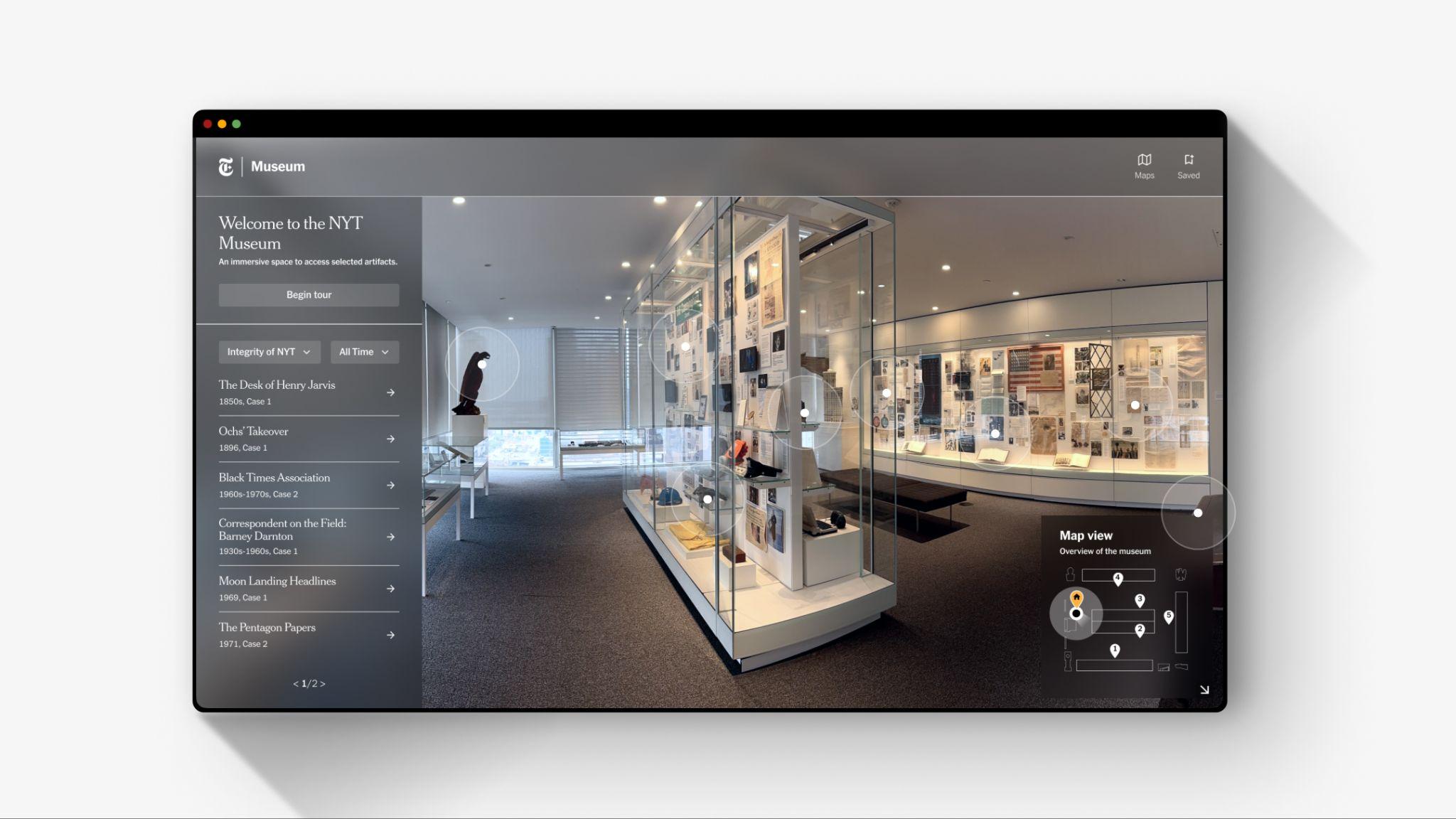

Imagine walking through a museum where interactive pins emerge as you explore, each one a gateway to discovery. Tap a pin, and you’re transported into an immersive space where history comes alive through a scavenger hunt game, revealing the stories and secrets behind each artifact. This is the experience Nuoran Chen and his team brought to life in their product demo video for The Virtual New York Times Museum. The project reimagines a hidden gem: the New York Times Museum tucked away on the 15th floor of the NYT’s office building, accessible only to employees who work there. Chen and his team’s vision opens this space to the world, showcasing over 170 years of journalistic history through an innovative virtual experience. The concept design earned them top honors at 2025 International Design Excellence Awards (IDEA). Behind the project is the main designer, Nuoran Chen, whose work is shaped by a long-standing interest in inclusive design.

Nuoran Chen grew up in an era when information has never been more readily available. Yet, he argues, it is this abundance that has made designers complacent—assuming everyone has easy access and overlooking those who still face barriers. His passion lies in bridging this gap: making services or information more accessible and reachable to those with limited abilities. Over the past three years as a product designer at major media companies like The New York Times and The Washington Post, he has worked to embed inclusive thinking from concept to commercialization throughout the design process. In his personal projects, he takes his commitment further by inviting users into the decision-making process. These principles come to life across three projects that reveal different dimensions of his approach to inclusive design.

The virtual New York Times Museum project exemplifies Chen’s commitment to making exclusive physical spaces digitally accessible while maintaining the authenticity of its physicality. In his role on the project, Chen focused on translating the museum’s solemn, in-person experience into a digital one through a unified design language that guides users throughout the entire journey. He didn’t simply create another online gallery where users scroll through grid-displayed images. Instead, he used photogrammetry to capture the physical space itself, creating a digital twin that preserved the museum’s atmosphere and spatial relationships. He also designed the spatial UI system that supports the entire experience, from museum navigation to scavenger-hunt interaction.Interactive pins anchor artifacts to their actual locations within the digital twin, surfacing naturally as users explore the space. This recreates the feeling of strolling through a museum in person, delivering a serious yet engaging experience: the UI is intentionally restrained, fading into the environment to foreground journalism while offering subtle cues that guide exploration and interaction. Audio descriptions are included for each artifact, extending the experience to audiences who prefer or rely on audio. Through this project, Chen demonstrates how design can remove barriers to physical access while preserving the authenticity of the original experience and deepening engagement.

Chen’s work for inclusive design also extends to the system-level that powers accessibility for all products. At The Washington Post, Chen’s work on the internationalization of the content management system exemplified this thinking. He improved the accessibility of design systems and helped the company reach more clients who use Arabic and Hebrew through his right-to-left (RTL) language adoption guidance. Chen emphasized that RTL adoption isn’t simply mirroring components on screen—it requires an exhaustive design of information hierarchy, interaction gestures, and iconography within specific cultural contexts. He created the first component-level documentation on RTL for The Washington Post ArcXP design system, which includes all these nuances that helped different teams build with intention, ensuring consistency across the platform. For Chen, this work proved that improving accessibility at the design system level creates a win-win outcome: “For companies, teams can build products faster and generate more revenue sources while reducing legal risk; for users, the product is more usable and accessible.

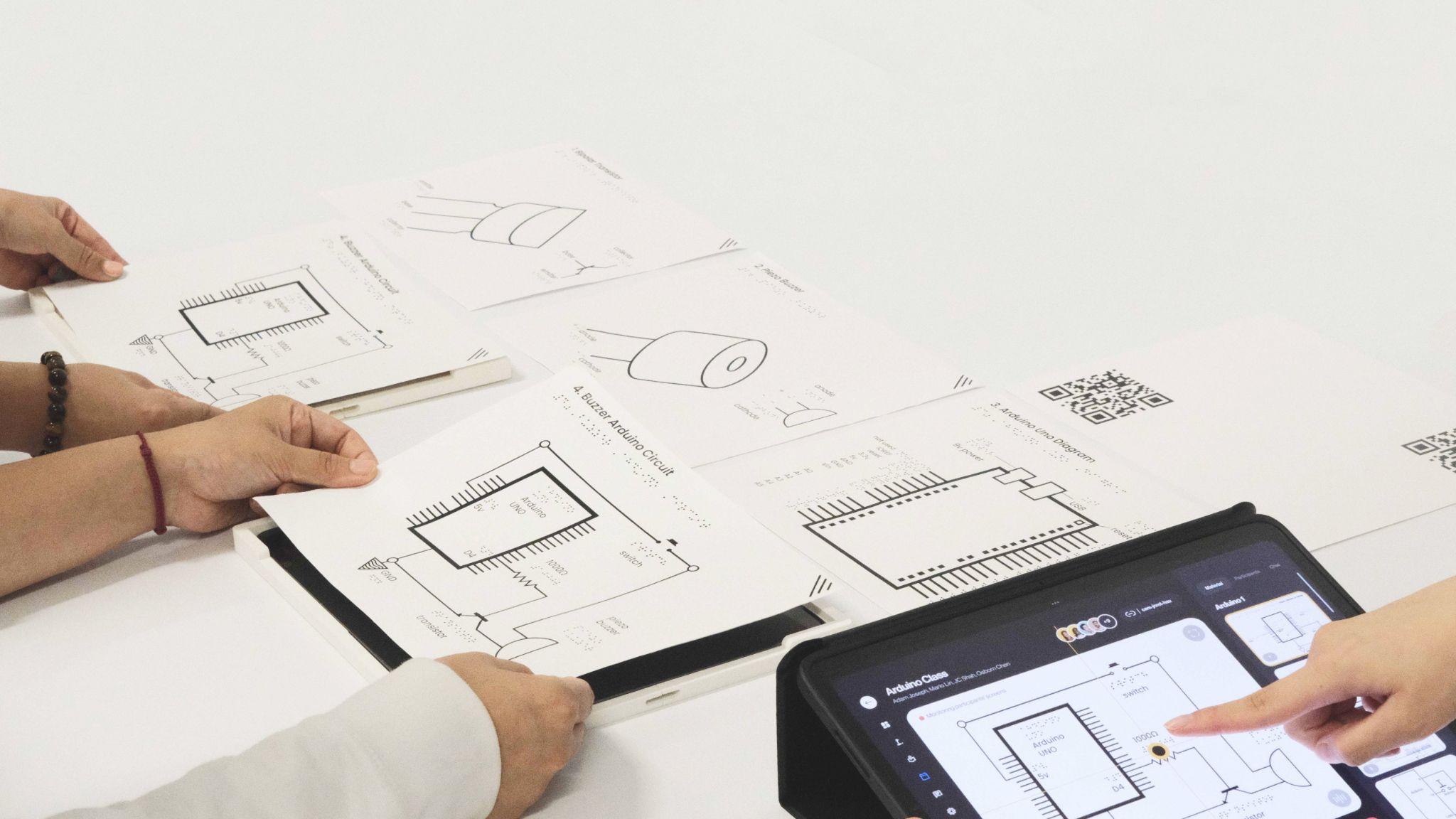

TactileLink, Chen’s personal project, takes his inclusive design approach to the design process itself. It challenges the conventional design process where solutions are created first and users consulted later. When Chen and his team volunteered at a Blind Arduino class at the East Bay Center for the Blind, they observed the instructor physically guiding each student’s hand across tactile diagrams one-on-one. This approach made teaching multiple students challenging. Rather than designing a solution in isolation, Chen brought the blind students and instructors into the process from the start. Together, they brainstormed ideas, built prototypes, and tested solutions in real classroom settings. The result was TactileLink, a tactile graphic teaching system that makes in-class or remote tactile graphic education more accessible. One instructor can now teach multiple blind students simultaneously. Students can easily locate elements by audio feedback: as they move their finger across a diagram on a tablet, the pitch shifts—rising near target elements, falling when they drift away.

Taken together, Chen’s work reflects a consistent approach to inclusive design that extends beyond individual deliverables. While often working within large, collaborative teams, he has taken on roles that shape both how products are built and how their impact is understood—whether by defining interaction models that preserve physical context in digital spaces, establishing system-level standards that guide future teams, or reframing accessibility work so it is recognized as innovation rather than accommodation. Across institutional projects and independent initiatives alike, Chen demonstrates that inclusive design is not a fixed set of techniques, but a strategic practice that requires advocacy, cross-disciplinary coordination, and long-term thinking. His work highlights how designers can expand access and reach at scale, even within complex organizations where accessibility was not originally prioritized.