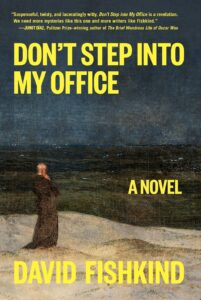

When aspiring writer Jacob Garlicker witnesses a murder on the eve of his twenty-sixth birthday, it sets him on a spiral of overthinking and (lukewarm) literary ambition. After his agent-turned-girlfriend fails to sell his novel, he meets his wife, and years later, sober and somewhat satisfied, joins her family for what should be an average birthday celebration in the Hamptons. But after a similar event shakes the community, Jacob is spurned to go on a quest to find the perpetrators, no matter if he relapses on weed, alcohol and good sensibilities—he might get a good book out of all of this.

Quick-witted, propulsive and devilishly funny, Don’t Step into My Office is an alt-lit thriller for the ages. David Fishkind chats with OurCulture about Jewish neuroticism, Jay Gatsby and male ennui.

Congratulations on your debut novel! How do you feel with it so close to being out?

It feels different every day. Sometimes I feel very excited, sometimes I feel dread. I’ve worked in obscurity for a long time, so it’ll be something of a change.

What made you want to combine a sort of sharp, alt-lit style with the mechanics of a thriller?

I’ve been writing fiction for almost 20 years now, and for the first 10 years or so, I was very influenced by hyper-minimalist realism. And at a certain point, I started to feel myself coming up against limitations with that. Even more than I care about writing, I care about reading, so I wanted to find a way to engage in the storytelling I value as a reader. And I didn’t really know how to write plot; I was focused on highly polished sentences and style. I was curious how genre could be elevated, so I started reading horror literature, crime literature. It just started naturally influencing and broadening the work I had already done.

Tell me about Jacob Garlicker, a sober writer trying to redeem his failed novel. Did you ever use yourself as a jumping-off point?

Yeah, even when I sold the book, the character’s name was “David Fishkind.” I had been working in that metafiction milieu for several years, where I liked playing with reality collapse and felt the most honest thing was to have the protagonist be named David Fishkind and resemble me. Maybe when I started doing this, it was sort of a novel idea, but hard autofiction is fairly oversaturated now. In the same way I didn’t want to limit myself to realism anymore, I didn’t want to limit myself to this lens of self-reflexiveness. Jacob Garlicker is pretty much 100% based on me, but the more freedom that I gave myself with him as a character, the more I was able to remove myself from the page and create an effective protagonist.

In the book, the publisher FSG rejects Jacob’s novel and says that “novels of male ennui are perhaps a little plentiful at the moment.” Do you think there’s a way forward for the sad literary man?

I’ve seen a lot of people comment on this over the past few years, and frankly I think that it’s always been and remains very easy to be a sad cishet literary white man. I don’t think his time ever went away. If people were demanding more varied perspectives in books… I just never felt particularly threatened by the industry push for a broader series of approaches to novels. I think if anything, it made the demand that if you just wanted to write books of male ennui—right next to me I have Tropic of Cancer—you have to rise to the occasion and write good literature. You shouldn’t just be able to get by on that trope.

That comment, novels of male ennui are a bit plentiful, is from a rejection letter I received in 2017 in trying to sell another novel. To me, it seemed like valid commentary. If the book isn’t speaking to an audience, and even if it is, you can always improve on the writing.

A lot of your writing concerns the ins and outs of publishing, notably its desperation when things don’t go well. What endeared you to this subject?

I use Jacob as an opportunity to examine these feelings of propriety with regard to publishing. When I was younger I was like, ‘Well, I’ve read so many books, I’m very educated, I should just be able to publish novels.’ I think a lot of Jacob’s frustration and desperation should be taken with a grain of salt; he’s ultimately dealing with a sense of entitlement that is generationally endemic. Millennials felt that if they went to college and networked with the right people, the world would become their oyster on their terms. To a certain degree, that was imposed by the culture of the time. [But] there were some harsh realities economically—this is not our parents’ economy, our parents’ America. You don’t just get what you want by following a set of rules and hobnobbing with certain figures. Jacob doesn’t really have the work ethic, so he defaults on drug use and self-pity and navel-gazing. I think what I’m trying to get at is a broader current in artistic ambition and creative professions. And what a hellhole narcissists can create for themselves and everybody in their surroundings.

He has the idea that Jay Gatsby might have been Jewish, and at parties tells people to check his Twitter (@gatsbyjewish) for his explanation. What made you think of this theory?

When I first finished a draft of this novel, I didn’t have the Gatsby stuff in there. I’d written this story, still had bumbling Jacob, not sure what he’s working on. But something felt glaringly missing. I try, often, just to read my way out of stuck moments. I’ve read The Great Gatsby four or five times—it’s a two-day read, and also, pretty much, the perfect novel. Top five novels for me. And it’s a good summer book. So I picked it up, and with Jacob’s desperate paranoia still in the front of my consciousness, I noticed, for the first time, not just how many references there are to white supremacy, but also how many there are to semitism and antisemitism. Not a tremendous amount, but I think enough evidence to convince yourself Jay Gatsby’s harboring some Jewish secret, some ethnic shame. Mind you, there are historical arguments that he’s Black. I’m not proposing that’s my take, but it’s certainly a rabbit hole you can go down, and that worked thematically with everything else in the book. It fleshed out that incomplete feeling I was struggling with in terms of Jacob’s trajectory and presented a nice foil to his egomania and persecution complex.

Jacob says, “I could be no one’s first choice for a protagonist.” Why do you think he feels this while he’s in the middle of one of the most notable weekends of his life?

I guess it’s buying into the idea that the white male ennui guy is played out. Also, from people telling me that the writing I had done was not going to connect with readers at large because of its erratic emotionality. Even close friends told me that Jacob Garlicker wouldn’t appeal to someone for the length of an entire book. He’s too neurotic, too self-obsessed, too drugged out. I really felt like there are people like him who aren’t amplified because we don’t like to amplify the voices of losers. Jacob is objectively a loser, and that’s something I like about him. I indulge the most pathetic, obnoxious things about being in one’s early 30s in the 2020s and try to both represent it as very cringe and very off-putting, but also real and lovable. There are a lot of people who feel like they shouldn’t be the protagonists of their own lives—that’s why they look at social media all day. Jacob isn’t written to help sad boys, necessarily, but he is a reflection of a much larger trend.

I enjoyed the depiction of friendship in this novel, whether it be one with history, like with Miriam, Alexander and Matthew, or random people getting along at a party. It felt sort of hopeful in a way, even though they were enshrined by alcohol. What were you aiming for in these scenes?

Being very online in the 2010s I was inundated by all these articles concerning the nature of male friendships, or lack thereof. As men age into their 30s and 40s, feelings of alienation and obsolescence seem to increase, resulting in the loneliness epidemic we keep hearing about. Not to mention the way culture perpetuates the myth that one’s teens and twenties should be the most meaningful and active social period of your life. If you settle down, you focus on somebody else’s life, whether it be your partner’s, or career’s, a child’s. A lot of the book is about mourning those relationships. In my twenties I had a handful of friends and I could walk to their apartments, but the way our society is structured, it’s not very easy to maintain those bonds. I think Jacob is striving to nurture everybody in his life as a way to soothe himself in the face of existential dread. There’s a competing sense of misanthropy, while also trying to sustain connections and build on love.

After a conversation about Didion, Jacob says, “Men can’t have babies. Telling stories is the closest we’ll ever get.” Do you agree?

Can’t men have babies? I dunno! I don’t want to speak for men. Telling stories, for me, would be the closest thing, given that I’m not a father and don’t necessarily have fatherly ambitions. Literature is my way of participating and connecting. Even if I’m not connecting with people directly, it’s my gesture of legacy or inheritance. I don’t know what I would do if I couldn’t read stories. It’s through narrative that I’m able to make the slightest insights into the larger chaos of existence. That’s just how my mind works, and I find I’m able to develop more empathy and learn more about the world by engaging in stories. Writing fiction is my attempt to pay that forward.

What’s next for you as a writer?

I’m working on a new novel, it’s early-stages, but I have it outlined and it’s gonna be different. I’m trying to create a continuity between the works. I’ve written like four other manuscripts that I have no intention of publishing, so I now have a pretty good sense of how to approach writing books in a professional way. I don’t want to say too much, because I get more freedom out of it when I don’t tell you much, but yes, I am going to write more novels.

Don’t Step Into My Office is out now.