Memory rarely returns as a complete image. More often, it appears as something partial and unstable, a residue that hovers between presence and disappearance. It can feel light, translucent, almost atmospheric, like mist suspended between what is remembered and what can no longer be reached. Rather than belonging solely to the past, memory continually folds into the present, reshaping perception as it lingers.

It is within this uncertain terrain that Qingran Liu’s artistic practice takes shape. Working across textiles and moving image, Liu approaches memory not as something to be reconstructed or narrated, but as an experience activated through material, perception, and bodily proximity. Her works do not offer memory as evidence; instead, they stage memory as a condition, fragile, unstable, and perpetually in motion.

Liu’s practice consistently resists linear storytelling. Instead, it unfolds through sensory encounters shaped by duration, repetition, and natural rhythms. Textile, a medium that is simultaneously soft and rigorously structured, becomes central to this approach. Within her installations, memory is not retrieved as a fixed record but emerges through processes of distortion, interruption, and reassembly. The emotional register of her work is restrained and introspective, leaving space for hesitation rather than resolution.

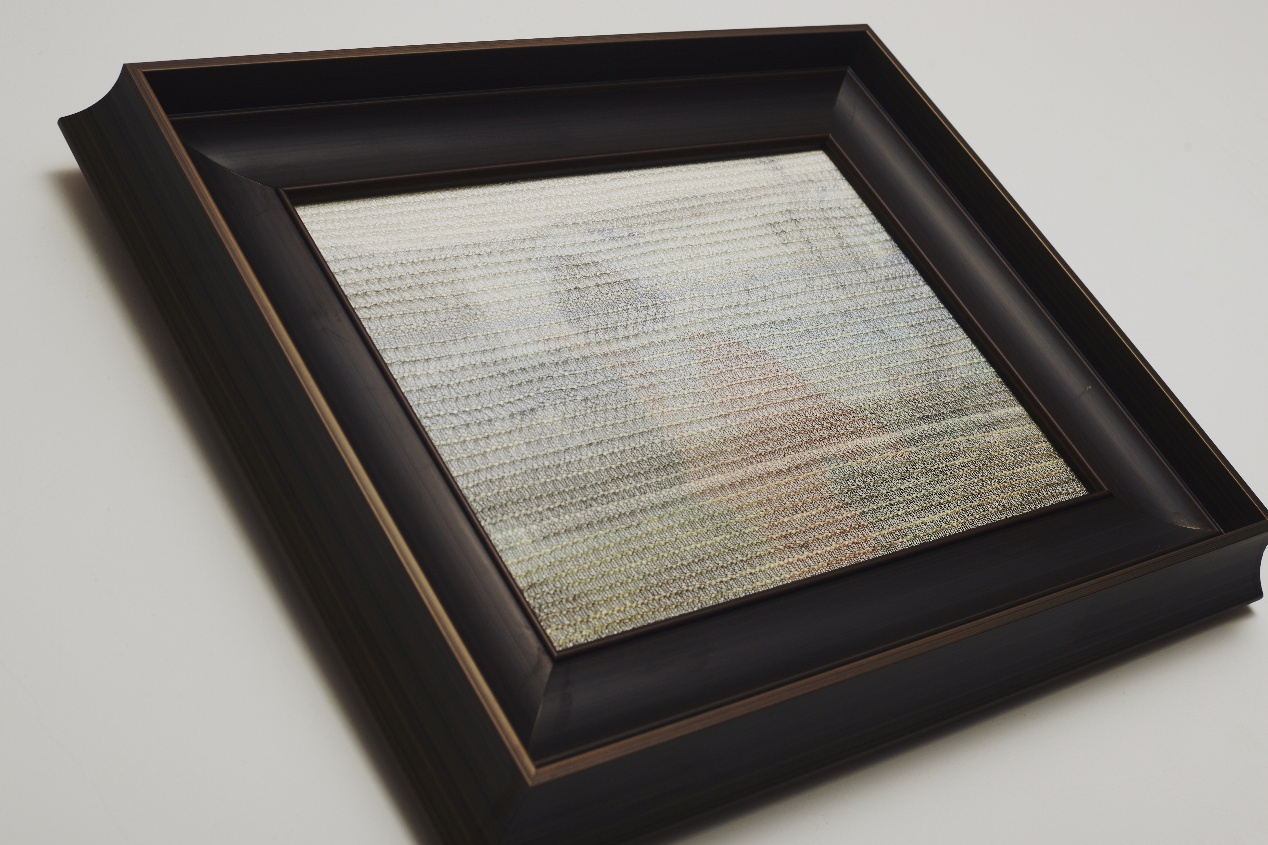

Much of Liu’s work occupies the threshold between image and fabric. Fragile yarns intersect with fragmented photographic imagery, producing surfaces that seem to waver between legibility and dissolution. She works primarily with a Dubied industrial knitting machine, whose mechanical precision establishes a disciplined underlying structure. Against this rational framework, the yarn introduces vulnerability: threads shift, misalign, or partially disappear, generating visual instability that resists permanence. The image never fully settles; it remains contingent on light, distance, and the viewer’s position.

Rather than treating the machine as a neutral tool, Liu positions it as an active mediator between logic and sensation. The ordered system of industrial knitting becomes a site of tension, where deviation carries emotional weight. Textile, in this context, is neither purely structural nor purely expressive, it exists in a quiet negotiation between control and fragility, calculation and intuition.

Within contemporary textile and image-based practices, Liu’s work may initially recall artists who translate photography into fabric. Yet where such practices often emphasise layering or sculptural density, Liu moves in the opposite direction. Her works cultivate flatness, transparency, and suspension, evoking the sensation of memory as something that hovers rather than accumulates. What remains visible is never fully anchored; it appears to drift at the edge of perception.

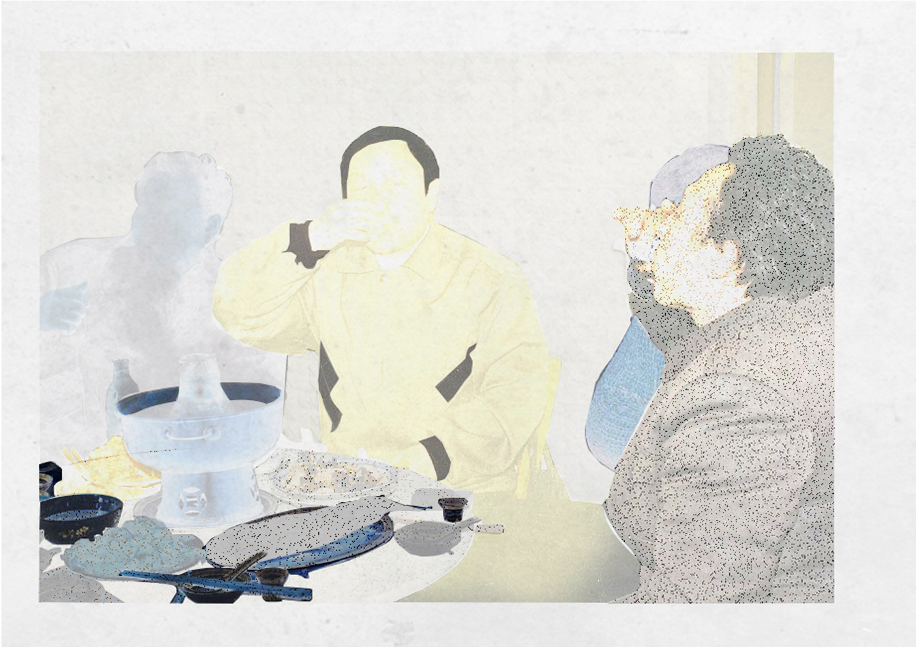

In the series The Non-returnable One: A Study of Memory Based on Photographic, Liu turns to her family photo albums. These images, once anchors of familiarity, gradually become unstable through repeated viewing. As time passes, inherited family narratives bleed into her own subjective recollections, blurring the boundary between personal memory and collective construction.

Liu translates these photographs into knitted and printed textile images, deliberately disrupting their structure so that recognisable forms slowly distort. Faces remain partially visible yet never fully accessible, as if memory itself were fraying at the edges. The act of translation becomes a process of erosion, in which clarity is steadily compromised.

Yarn functions here not simply as material, but as metaphor. Liu works with monofilament, rigid, transparent, and easily broken, a material defined by contradiction. It is simultaneously present and vanishing, resilient and vulnerable. This condition closely mirrors the nature of memory: it leaves traces that shape us, yet resists total grasp. What endures is not certainty, but tension.

In Linkage 1, Liu begins with a photograph of a family gathered around a dining table. What once suggested warmth and intimacy is gradually unsettled. Faces stretch and drift apart, while the table, a symbol of cohesion, loses its structural clarity. The image no longer affirms harmony, but exposes an underlying fragility embedded within the scene.

As viewers move around the work, perception shifts continuously. Transparency causes the image to appear suspended in space, changing with each bodily movement. Viewing becomes an active process, shaped by distance, angle, and duration. This instability often resonates with viewers’ own experiences of family memory, familiar yet indistinct, intimate yet unreachable.

Rather than locating emotional impact in a single visual detail, Liu allows ambiguity itself to carry affective force. The inability to fully decipher the image becomes its most potent quality, activating memory through uncertainty rather than recognition.

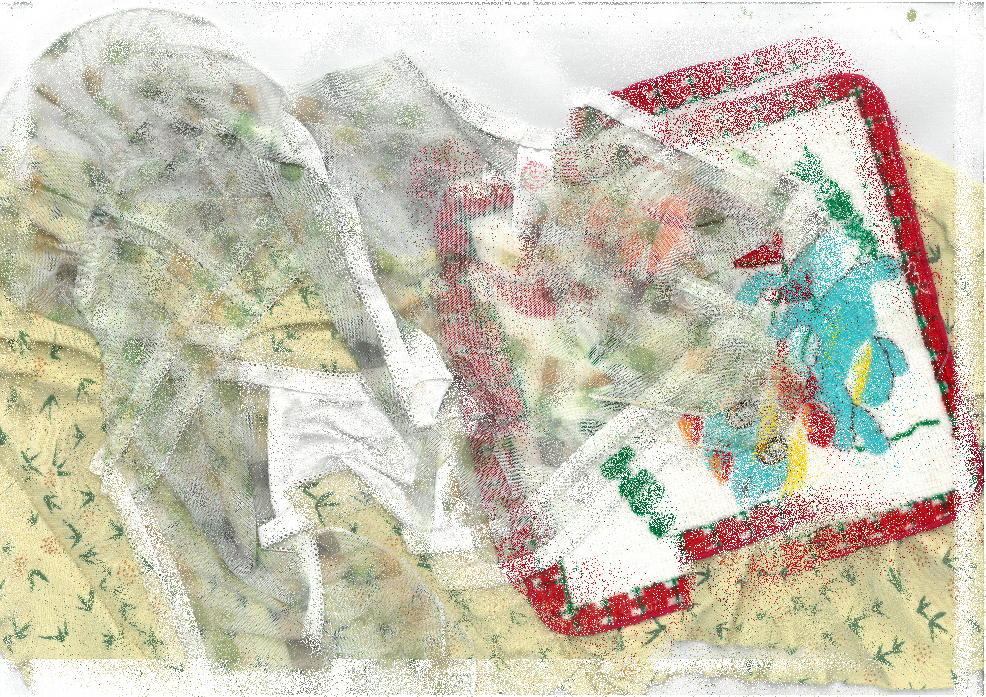

In her 2023 project Funerals under Formalism, We Pretend to Cry, Liu expands her inquiry from personal memory to cultural structure. The work originates from her experience of attending a family funeral, a setting marked by elaborate ritual yet an absence of emotional release. This dissonance prompted her to examine how formalised mourning practices can regulate, rather than express, grief.

Returning to her hometown, Liu collected personal belongings and family photographs, scanning and collaging them into textile prints. Touch becomes crucial in this process. Handling garments once worn by relatives introduces a bodily form of remembrance that compensates for emotional distance. The resulting images resemble afterimages, faded, fragmented, and uneven, as though time itself had interfered with their clarity.

The installation combines flat textiles, fragmented mannequins, and enclosing structures, forming a provisional environment of remembrance. Rather than presenting a static memorial, the work functions as a spatial condition that viewers must physically enter. Movement through the space is constrained, producing a subtle sense of pressure and restraint.

This environment operates less as a representation of mourning than as a simulation of its mechanisms. Viewers are positioned within a ritualised setting, yet denied emotional release. Discomfort arises not from spectacle, but from quiet suppression. The work poses an unsettling question: when grief is formalised into obligation, what happens to genuine mourning?

Unlike practices that foreground communal memory or collective identity, Liu’s work remains inward-facing. Her installations do not seek catharsis or overt social critique. Instead, they construct introspective spaces where loss, restraint, and emotional inheritance can be felt rather than explained.

Across her practice, Liu treats textile as a vessel, one capable of carrying personal memory while exposing broader emotional structures. Fabric extends the body, absorbs touch, and records time through wear, tension, and distortion. In doing so, it becomes a quiet but persistent medium of reflection.

Qingran Liu’s work resists closure. It sustains open perceptual fields in which viewers become participants rather than observers. Through transparency, softness, and structural tension, her installations evoke spaces where memory is neither fully present nor entirely gone.

In this sense, “soft resistance” emerges not as opposition, but as endurance. Liu does not confront forgetting through force or declaration. Instead, she works through delicacy, allowing memory to surface slowly, through material hesitation and sensory attention. What remains is not a statement, but a lingering vibration: a quiet insistence that what is fragile, blurred, or unspoken still deserves to be held.