Hayes Greenwood is a London-based artist working primarily in painting, alongside sculpture, video and installation. Her deeply charged works draw on lived experience, using landscape and natural motifs to explore life, death, desire and embodiment. She combines the familiar and the otherworldly, translating complex emotional states into heightened visual forms where internal and external fold into one another. Hayes Greenwood combines the familiar and the otherworldly, translating complex emotional states into heightened visual forms where the internal and external worlds collapse and fold into one another.

Hayes Greenwood has exhibited internationally, including solo shows at Castor (London) and GiG (Munich), as well as group exhibitions at Stuart Shave Modern Art (London), Mana Contemporary (USA) and Saatchi Gallery (London). She is currently working on a major commission for Hospital Rooms and has recently undertaken residencies with theCOLAB: Body & Place (2025), Hogchester Arts (2024), and was awarded the Palazzo Monti x ACS Residency Prize (2024). She holds an MA from City & Guilds of London Art School and is the co-founder and former director of Block 336. Her work is held in many public and private collections.

Was there a particular moment when you understood that creating art wasn’t just something you loved, but something you wanted to devote your life to?

It didn’t arrive as a singular moment; it was a slower process than that for me. I’ve always been surrounded by art and creativity in culture both high and low. Making is something I’ve always loved and just never been able to stop doing.

Though she didn’t do it later in life, my mum was a skilled painter, and my stepdad had a deep love of art and literature. He was very involved in Salts Mill in Yorkshire when I was growing up. He was a friend of David Hockney’s, and I always loved Hockney’s drawings and opera sets when I was a child. As a kid, being an artist seemed like a very fun and compelling way of engaging with the world!

I followed a fairly standard path: art A-level, an art foundation, then a BA and MA. After completing my BA, I set up Block 336 in Brixton, a large artist-run gallery and studio space which I ran for over a decade, commissioning major solo projects by other artists with an ambitious public programme. I’ve taught in art schools for the past 15 years and these experiences reinforce that art isn’t just about individual practice but about connection, exchange and deep learning.

I think art will always be a way to orient myself in the world. It continues to be a source of pleasure, a place to time-travel, play, think and process moments that are confusing, painful, unresolved, intense, joyful, wonderful or strange.

You mention that the paintings you created for Weird Weather have all ‘expand[ed] out of a kind of grief logic.’ How did creating this body of work challenge or affirm your previous beliefs about the relationship between art and grief?

Well, artists have always made work to understand their feelings and position in the world. There is a lot of grief in art in one form or another. Edvard Munch is often quoted as saying that “art comes from joy and pain, but mostly pain.” It is said that grief is the price we pay for love, and Bell Hooks writes about this. She talks about it not being simply about loss, but about how it is a testament to the depth of our bonds. She describes it as evidence of our capacity to love deeply and remain open and affected by the world rather than defended against it.

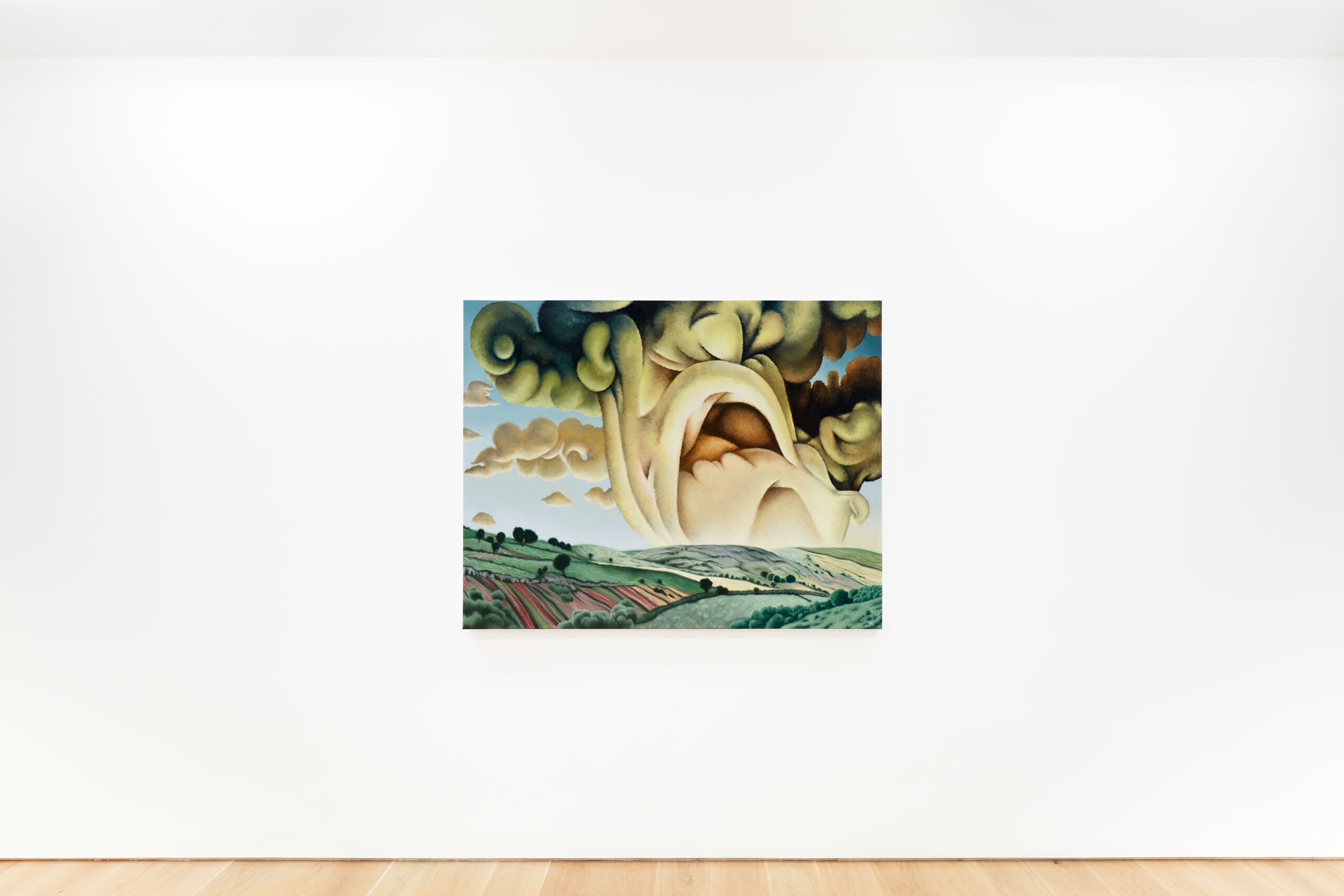

In making Weird Weather, this perspective became tangible through the way the work responded to place and memory. The paintings grew out experiences shaped by transition and change, but also by attachment and connection and to the sense of poignancy and sharp relief that accompanies significant life events. Working urgently and intuitively allowed the work to expand, embracing both intensity and tenderness. Grief is not one-dimensional; it isn’t singularly heavy or painful. It is prismatic, generative, wild, psychedelic and transcendental. It can expose what it is to be alive and present in the world and locates you in a heightened state of awareness and openness.

Reading your description of grief as a prismatic state – where love, pain, gratitude and acceptance can coexist – reminded me of a beloved quote by Rilke: “Death is our friend precisely because it brings us into absolute and passionate presence with all that is here, that is natural, that is love.”

When you were working on Weird Weather, did painting become a way of entering that heightened presence? Or did it function more as a space to hold contradiction, where opposing emotional states could sit without needing resolution?

That is a beautiful quote. I would say both, and more. Love and loss really throw you around; they produce a kind of Shakespearean madness, and painting, for me, became a container for all of it – a way to be in a state of heightened presence, to hold emotions that splinter and overlap without needing them to be resolved or in order. At the same time, it was a way to connect with love and beauty, to feel deeply, to process and be grounded, to transform something painful into something creative, to channel, to sublimate, and to experiment and play.

There’s a persistent idea that some of the most beautiful or resonant art is born from life’s most painful experiences, especially profound loss. Do you find that notion reductive, or does it ring true in your own experience?

It can be true. Pain opens you up to depth, intensity and transformation. Equally though, joy, curiosity and wonder are very fertile ground, and they feed and exist in art in ways that are very profound. These things sit on two sides of the same coin and often can’t be separated. For me, creating Weird Weather was motivated by a significant loss, yes, but it was also shaped by a connection to love and so much of what I think is beautiful. When I’m making work, I’m frequently trying to engage with that which I don’t fully understand – the deep, gritty, weird and surprising parts of experience. For me, making is ultimately about embracing all of it and letting it guide the work.

Were there any works in Weird Weather that genuinely surprised you, where you started with one emotional or visual intention but the painting took you somewhere completely different?

The paintings all start with drawings, but before committing to making the paintings I allowed the drawing stage to be very open – many of them took me in unexpected directions. The logic of the works was shaped in part by my connection to landscape and home. The paintings reference the hills of the Pennines where I grew up. Rather than depicting the landscapes literally, I allowed internal and external states to fold into one another, attempting to push bodily sensation through weather and geography.

The larger paintings are a decent scale, so physically they were quite immersive. There is always a dialogue between intention and discovery in the making that keeps the work alive and unpredictable, pushing colour and touch to carry feeling and sensation. I would try things within the paintings and go off in mad directions, often returning to something closer to what I originally intended. But you have to explore and take these flights of fancy to see what comes of it – and the history and remnants of those journeys remain.

Thinking back to The Witch’s Garden, which engaged deeply with marginalisation, folk knowledge and gendered authority, I’m curious how earlier bodies of work continue to live inside newer ones. Do processes or emotional strategies ever bleed forward, or does each series demand a complete reorientation?

The core is always the same and earlier bodies of work definitely live inside newer ones, even if the surface concerns might feel different.

The Witch’s Garden was similarly motivated by an autobiographical starting point, tracking my experience of trying for and later having children. It was through researching the origins of the love heart symbol that I came across the history (likely fake news) about a now-extinct plant called silphium, which was apparently an aphrodisiac and contraceptive and was said to have a heart-shaped seed. That set me off into researching plants and their histories, which are of course inextricably entangled with our own. Contextually, the research was so rich and fascinating that I couldn’t stop making the paintings – there are about 60 works in the series. These plants and flowers I was painting became containers for emotion, story and history, but I also always saw them anthropomorphically – as characters in their own right. For Weird Weather that gaze has shifted outward toward landscape – there has been a kind of zooming out.

I have always connected to William Blake’s description of double vision – seeing the world as more than it appears, one thing looking like another, or seeming to express something emotionally. Pareidolia is a familiar phenomenon and my children are always pointing things out, saying, “that looks like X.” It’s quite a trippy or childlike way of seeing the world that has always been with me. I think it’s a useful, generative thing to take note of and what is happening inwardly and outwardly often mirror and inform one’s understanding of experience.

Finally, what is something you wish more people understood about the experience of being an artist?

Well, I was right as a kid – being an artist is a very fun and compelling way to engage with the world! It’s the best thing in so many ways, but as someone who lives in a semi-permanent state of existential awareness, it can also be intense *laughs*! Art takes you to the craziest places and introduces you to amazing people but there is no road map and the path can be tricky to navigate. Artists are constantly balancing creative exploration with practical realities and right now, with a tough economy and arts funding becoming ever harder to access, it can be challenging. Being an artist is not always easy, but I wouldn’t want to do anything else.

Jane Hayes Greenwood’s Weird Weather, presented jointly by Ione & Mann and Castor, is available to view 23 January – 7 March 2026.

Opening hours

Wednesday–Friday: 11am–6pm

Saturday: 12pm–4pm

Tuesday: By appointment only

Location

1st Floor

6 Conduit Street

London W1S 2XE