The film industry is much more than who we see on the silver screens. One of the behind the scenes maestros on the pulse of the film industry Yaxing Lin is an award-winning director and producer based in Los Angeles.

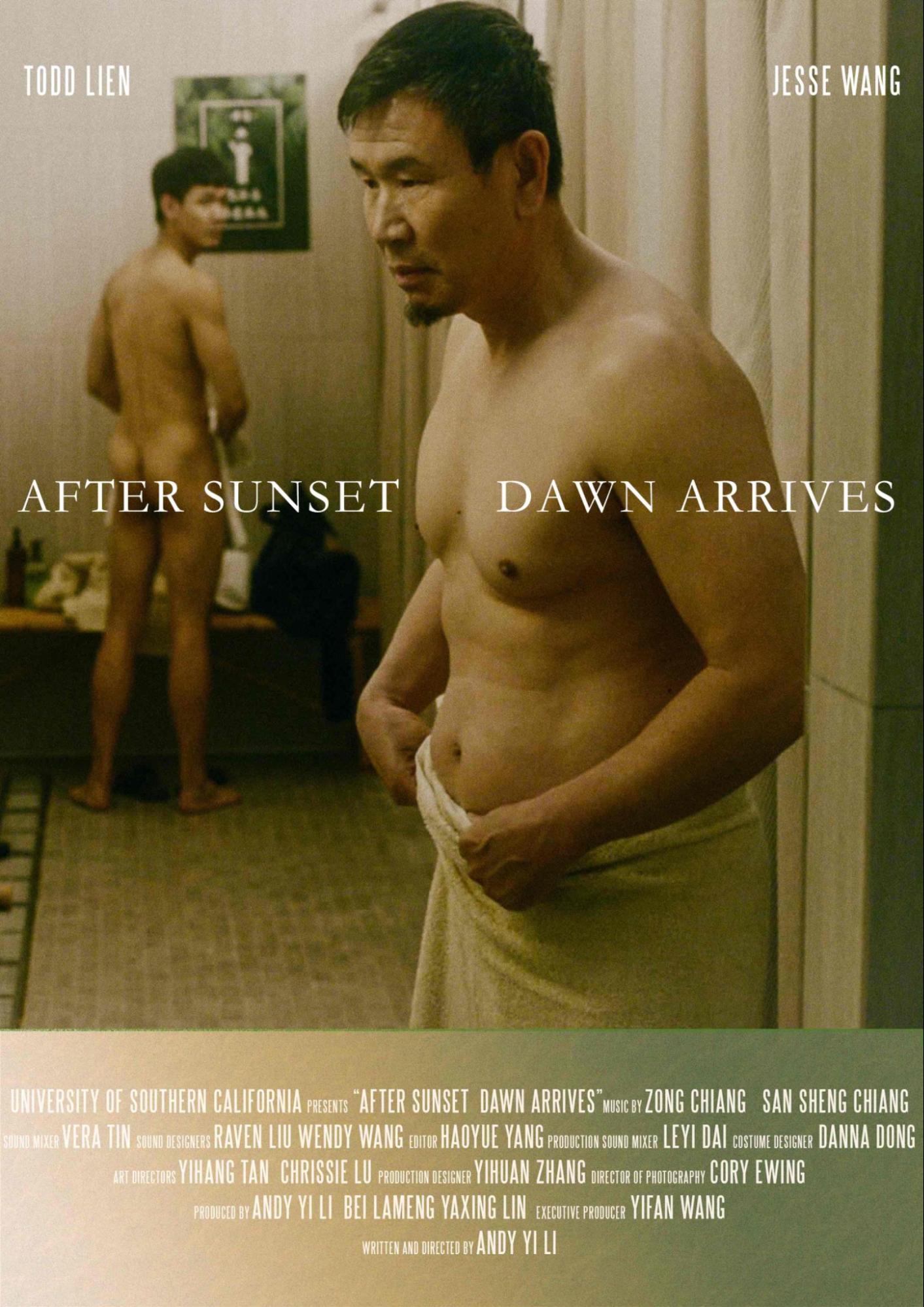

Her directing and producing credits include films focusing on marginalized groups and topics including “Playground,” “After Sunset Dawn Arrives,” and “The Things We Keep.” These films and others have been selected for the Sundance Film Festival, Outfest Film Festival and has been recognized with nominations and awards from the Sundance Film Festival, the Athens International Film + Video Festival, the Outfest Film Festival, the Seattle Asian American Film Festival, among others.

Lin speaks about her process as a producer, working on storytelling around marginalized communities and using “cinema as a space for reflection, rather than spectacle.”

What is the process like, as a producer, working on high profile short films?

Yaxing Lin: As a producer, the process begins long before a project enters production, and for me, selection is one of the most important decisions. Not every film will travel widely, and that’s okay. I’m drawn to projects based on personal alignment rather than surface-level appeal—stories centered on marginalized communities, women’s experiences, or voices that are often overlooked. I prioritize strong storytelling and artistic intention over novelty or spectacle. A clear, honest story is always more durable than a temporary hook.

In pre-production, my role is deeply collaborative. I spend a lot of time in creative development with the director, asking questions, stress-testing ideas, and helping clarify the voice of the film. I enjoy building teams during this stage—bringing together collaborators who not only have technical skill but also share a commitment to the story. Research is often part of that process. For “After Sunset, Dawn Arrives” (2022), we interviewed and worked closely with LGBTQ+ actors to ensure authenticity. For “Playground” (2024), I spoke with real sex workers in China and invited them into the filmmaking process, which informed both the tone and the emotional grounding of the film.

Financing is one of the most challenging aspects of independent production. Most of the films I’ve worked on relied on a combination of grants and crowdfunding. That requires strategic planning, transparency, and persistence. As a producer, it’s my responsibility to align the budget with the creative goals while protecting the sustainability of the project and the team.

Production itself is often intense—short schedules, limited resources, and high emotional investment. Producers become leaders, problem-solvers, and supporters all at once. Despite the pressure, these periods often become some of my strongest memories because of the relationships formed on set.

In post-production, I continue to provide creative input while helping shape a realistic festival and distribution strategy. For many independent films, we self-distribute, which means planning festival submissions and outreach ourselves. That stage feels like a harvest—seeing films travel to festivals we once only imagined attending and finding their audiences after a long, collective effort.

The film follows Wan as he navigates what Huck magazine called “queer utopia.” Is the conversations around LGBT Asian identity something overlooked?

“After Sunset, Dawn Arrives” tells the story of Wan, a Chinese man in his sixties who, after the death of his wife, begins to confront and explore his sexuality for the first time. I believe the film resonated with audiences because it centers on a form of courage that is rarely portrayed on screen—the decision to face one’s suppressed identity later in life, after decades shaped by cultural expectations and silence.

What moved many viewers was not just Wan’s sexuality, but his willingness to choose honesty at an age when society often assumes personal change has already passed. His journey reframes self-acceptance as something quiet and deliberate rather than dramatic. That emotional restraint allowed the story to connect across generations and cultures.

“After Sunset, Dawn Arrives” received significant recognition on the international festival circuit, including First Prize for Narrative Short at the 50th Athens International Film + Video Festival. The film also earned multiple juried and audience honors, including awards from the DGA and the Fargo-Moorhead LGBT Film Festival. It screened at major international festivals such as Outfest Film Festival, BFI Flare, and the Boston Asian American Film Festival, where it sparked sustained conversations around aging, desire, and LGBTQ+ representation within Asian communities. Following its festival run, the film reached broader audiences through streaming platforms including Amazon Prime Video, extending its impact beyond the festival circuit.

What is key when working with a director, as a producer?

For me, the most important part of working with a director as a producer is trust, built through a clear understanding of their creative vision. That means understanding the story they are trying to tell, the emotional core of the project, and the aesthetic language they want to use. A producer’s role is not to impose a vision, but to support it by assembling the right resources—casting, crew, locations, and schedule—within the realities of budget and time.

Equally important is logistics. Creative ideas only matter if they can be executed. A well-organized production structure allows directors to focus on storytelling rather than problem-solving. I spend a lot of time in pre-production making sure workflows are clear, communication is efficient, and expectations are aligned across departments, so that the set can function smoothly.

“The Things We Keep” (2025) is a horror film that ties into a family’s legacy in a home, it also shows how hoarding and trauma intersect. What went into production?

I chose to produce “The Things We Keep” because I was deeply moved by director Joanna Fernandez’s personal connection to the story. The film is rooted in her family history, particularly her relationship with her mother and the intergenerational trauma shaped by abuse, neurological illness, and memory loss. What resonated with me was how the script treated hoarding not as spectacle, but as a manifestation of inherited trauma and unresolved violence. Many people are unaware that hoarding is a mental health condition, and the story offered a rare opportunity to approach that subject with empathy and restraint.

At the time, I had just finished producing and directing the film “Playground,” which also explores childhood trauma and family relationships. Joanna had seen that film, and we connected through a shared understanding of how personal history can inform storytelling. That trust became the foundation of our collaboration.

Creatively, one of the main challenges was balancing genre and psychology. We wanted the film to function as a compelling psychological horror while also prompting reflection on generational trauma and mental health. That approach contributed to the film’s strong reception, including selection at the Sundance Film Festival, Screamfest, and FilmQuest, along with coverage from Variety and other outlets. The film was also selected for Delta Air Lines’ in-flight entertainment, allowing it to reach a broad international audience beyond the festival circuit.

From a production standpoint, resources were limited, particularly for visual effects. We combined practical effects with restrained VFX and precise editing to achieve a grounded, cinematic look. Creating the hoarder’s environment was another major challenge. We built the entire space on stage, researching real hoarding cases and collecting props over several months to create an environment that felt authentic and lived-in.

The project reaffirmed my belief that genre films can engage wide audiences while still addressing difficult emotional and social realities with care and intention.

What is next for you?

In the near term, I’m focused on two projects that reflect the direction and social weight of my work. I’m producing a feature documentary “You Tell Me How To Live” that I have been following for over four years and that is now entering post-production. The film focuses on immigrant communities and people living at the margins of society, examining how structural pressures shape everyday decisions around survival, dignity, and loss. The long production timeline allowed the story to unfold naturally, capturing real changes in people’s lives rather than imposing a predetermined narrative.

At the same time, I’m developing a science-fiction feature film, “The Line of Akedia.” The film engages with contemporary conversations around artificial intelligence, but approaches the subject from a philosophical and emotional perspective rather than a technological one. It explores how memory, agency, and human connection are affected as decision-making becomes increasingly mediated by intelligent systems.

Together, these projects reflect my ongoing interest in stories that connect intimate human experience with broader social and technological questions, and that use cinema as a space for reflection, rather than spectacle.

Photos: Producer Yaxing Lin on the red carpet of the Sundance Film Festival, DGA Awards.

Behind-the-scenes photos and stills are from “Playground,” “The Things We Keep” and posters of “After Sunset, Dawn Arrives.” “The Things We Keep”