Michał Korta is an internationally recognised portrait and documentary photographer based in Poland. He studied photography and German literature and has worked professionally since the mid-2000s. Korta is known for his strong, nuanced portraits of creators, including writers, musicians and painters, alongside long-term documentary projects exploring identity, social context and the human experience across cultures. He has published multiple photobooks, including Balkan Playground, a nuanced journey through eight Balkan countries, and The Shadow Line, which examines human–animal relationships in an intuitive, subversive way. Both have been exhibited in major institutions.

His other projects span Europe, Central Asia, Israel, Africa and beyond. He has received numerous awards, with his images exhibited across Europe and featured in international publications. In addition to his photographic practice, Korta contributes to photography education through teaching and writing, and collaborates with cultural institutions, galleries and publishers.

What drew you to the world of photography?

I’m not entirely sure what drew me to photography. I think it was more a coincidence, or rather, a series of coincidences. But on a rational level, I was drawn to the closed form of photography. In a photograph, the world can appear complete, even perfect in its imperfections. The older I get, the more I appreciate those imperfections. I find it profound — the tension between chance and intention, imperfection and control. Photography, unlike many other mediums, allows this paradox to exist in a single frame: a frozen moment that is both completely shaped by the photographer and entirely subject to the unpredictability of life. That “closed form” is precisely what gives photography its power. Every detail and imperfection is codified and preserved, yet these imperfections aren’t flaws. Rather, they’re part of the authenticity and the texture of the reality captured.

Robert Frank’s work embodies this beautifully. His images are often raw, uneven, even casual at first glance, but within that apparent spontaneity there is an exactness of vision. Imperfection becomes a lens through which a deeper truth emerges — a social commentary, an emotional resonance. It’s as if the photograph itself embraces the chaos of life and arranges it into something coherent, something that can be revisited and reflected upon.

In this sense, my own path into photography mirrors the medium itself: a combination of chance and intention, randomness and structure. That duality, that balance of control and unpredictability, is central to why photography continues to captivate me.

Your work is predominantly in black and white. Beyond the aesthetic, what does this choice allow you to express?

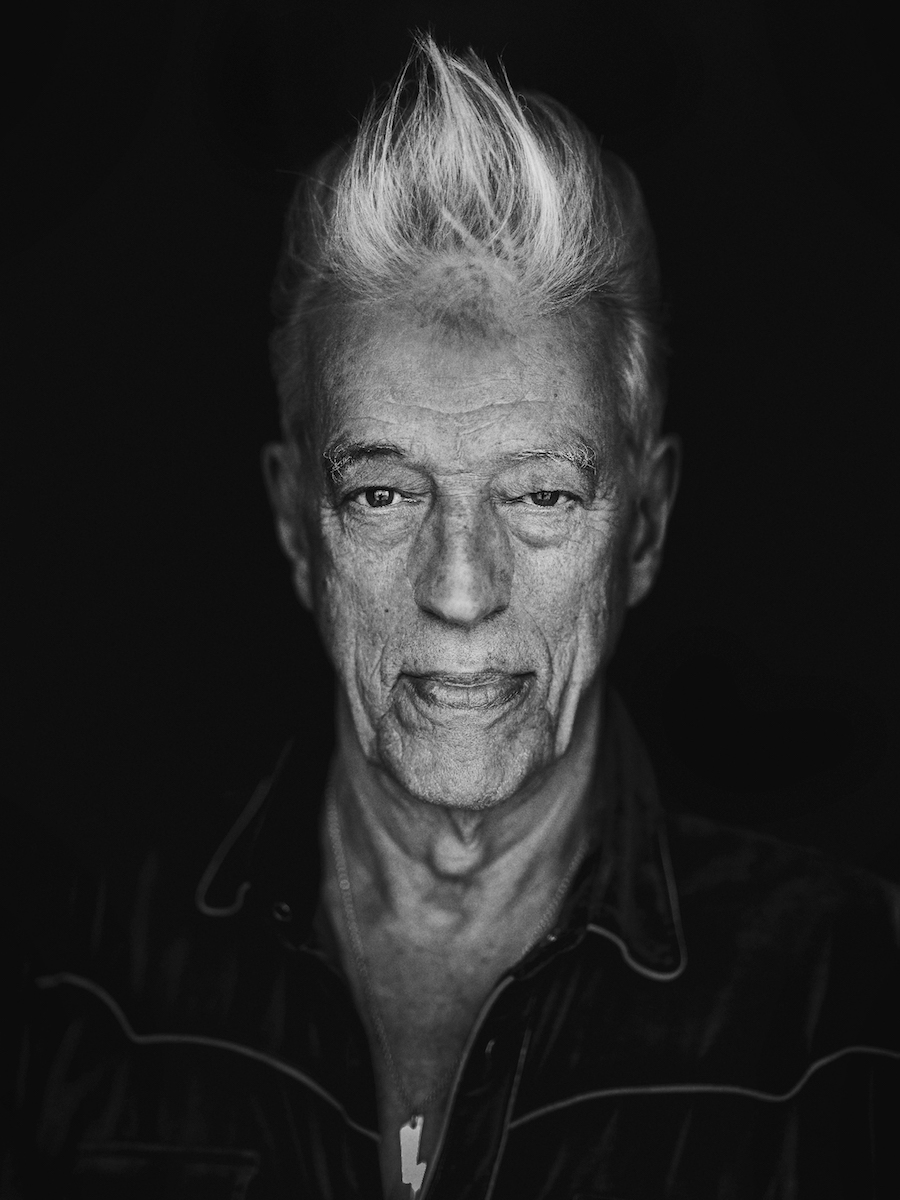

I work in both colour and black-and-white, but in recent years I’ve been increasingly drawn to black and white. Colour can be distracting; black and white simplifies the world, revealing only the grayscale and the power of illumination. Some surfaces reflect more light than others, human skin in particular, and I sometimes squint during a shoot to mentally strip away colour and better perceive the interplay of light and shadow.

I am a sun worshipper and deeply appreciate natural light. Even natural light can be modified; it can be a collaborator rather than just a given. In portrait photography, especially with today’s high-resolution cameras and advanced strobes, sheer brightness is no longer critical. Yet many young photographers confuse fully illuminated portraits with well-lit ones, producing bright, high-contrast images that don’t always use light effectively.

Lighting always has purpose, particularly in portraits. To sculpt a subject is not merely to place multiple light sources around them, which can conflict and dilute the effect. Light and shadow can be used creatively to emphasise form, define mood, and bring the subject to life. Mastering light and its direction, intensity, character, and interaction with surfaces requires observation, experimentation and patience.

You’ve photographed a diverse range of creatives, including musicians, painters, actors, and writers. What is it about fellow creators that compels you as a portrait photographer?

Knowing an actor or musician’s work doesn’t mean we truly know the person. It’s natural to admire their songs, paintings or performances, and meeting your idols can be exciting, but appreciation doesn’t automatically create a friendship. Sometimes connections happen when we share similar energy or worldviews, but that’s not guaranteed.

Creators are often people who take risks and aren’t afraid of failing. As the saying goes, “God loves a trier,” and this is a quality I deeply admire. Working with well-known individuals has its own challenges: their faces are familiar from magazines or social media, so the question becomes how to reveal something new, for instance, a hidden facet of their character or being. A good portrait, I believe, is a mixture of the sitter and the photographer. Ultimately, all cameras are the same; it’s the people on either side that make it unique.

A photoshoot is an exchange of energy. When we meet on the same level, we can inspire and elevate one another. It becomes a dynamic flow that can be greater than the sum of its parts.

Your books, particularly Balkan Playground, have received critical acclaim. When you’re selecting images for a photobook, what criteria guides your choices?

When selecting images for a photobook, I focus on storytelling. I often use surreal moments drawn from reality, and I value understatement, leaving space for the viewer to interpret and fill in the blanks. Reality can be surprising — you just need to open yourself to it and wait.

The process of selecting and editing images is complex and demanding. I wouldn’t say I’m a master of it because there is always more to learn. Over time, I’ve learned to trust a few close friends and collaborators, as different perspectives can greatly enrich a project. From there, discussion begins, shaping the final narrative and helping the photobook find its voice.

You’ve written that “what is left unsaid speaks louder than what is clearly stated.” Has your relationship with silence and subtlety changed over the course of your career?

Of course, when I started, I wanted my pictures to scream, literally, and to hit the viewer like a punch in the face. Nowadays, I see that as just one tool among many. What matters most is using whatever serves the image’s purpose best, whether that’s silence or a strong statement. In today’s overflow of images, the quiet, subtle ones often have more impact than the obvious or loud ones.

What emotions do you feel when you capture a photograph that feels ‘perfect’ to you?

When I capture a photograph that feels ‘perfect,’ I feel like I’m learning something from it. It surprises me — the perfect imperfection. Today, with Photoshop and AI, we can manipulate everything, but real art often comes from leaving a margin open and from allowing reality to surprise you.

Sometimes I’ve been very happy with an image and thought it was perfect, only to find that over the years its effect fades, and I no longer connect with it. Meanwhile, imperfect images, ones that are slightly unsharp, crookedly cropped, or even with a blurred finger in the lens, often stay with me longer; they feel more authentic and natural.

Sometimes, you have to embrace the flaws. Beware what you wish for.

Are there any specific themes or approaches you hope to explore more deeply in your work in 2026?

I always have several ongoing projects and countless imaginary ones in my head. Lately I’ve found myself daydreaming about selling all my equipment, cameras and lenses included, and stepping away from commercial photography entirely. With a single small camera and one fixed lens, I could dedicate myself to one personal project for the rest of my life. It probably won’t happen; I still have bills to pay, after all. But if I could do anything, that would be the dream: traveling for a year through Africa with just one fixed-lens camera. Perhaps this idea is already a kind of manifestation.

More realistically, in 2026 I hope to slow down, to see fewer images each day, and to resist the constant visual noise that surrounds us. I want to retreat into my own vision, to let it breathe and grow, and to continue perfecting a style of portraiture that is entirely my own. For me it’s less about producing and more about listening, noticing, and capturing what often goes unseen.

For years I’ve been making notes about photography, the philosophy of light and portraiture. In 2026 I’d love to begin shaping these reflections into a personal book. If there are publishers interested in thoughtful, reflective work on the craft and spirit of photography, I would be very curious to connect with them.

Considering all the lives you’ve observed and captured, what do you feel photography has ultimately taught you about being human?

I am still learning, but I often think of photography as a kind of wonderful university. It has taught me mindfulness, openness, attention to detail, sensitivity to light, and reflection on both myself as a human being and as a photographer. Sometimes, the moment I am fully focused on someone in the studio or on location matters more to me than the final image. For me, the process is more important than the result, even if the final image never existed. I am endlessly curious about people, both visually and spiritually.

I remember the first time I was at JFK Airport in New York: I felt like a little boy with his mouth agape, trying to take in everyone around him. So many faces, skin tones, ear shapes, pupils, hands, clothes, languages, even scents — it was overwhelming and exhilarating.

As a portrait photographer, I look at faces professionally, but that moment was a pure experience of human diversity, and it felt enlightening. I don’t know why, but I love working with people from different cultures and backgrounds. I often invite foreigners to my studio to talk, to hear their stories. I never stop wondering.

I am deeply grateful to photography for bringing me to this point, for opening my eyes and heart to the richness of humanity and for allowing me to keep learning, observing, and connecting every single day.