Andrea Dworkin, in my third wave feminist education, represented a reductive version of feminism. I had a snobbish attitude towards her. Her “anti-sex” and “anti-porn” radical feminist theories were unsexy and unattractive, all the things women are expected to be. At the very least, she was an unliberated figure who once publicly shamed Kathleen Hanna, de-facto leader of the Riot Grrrl Movement (and shining moment of women’s liberation in the nineties), for her time as a stripper. So I was somewhat startled to see, in the epigraph to the introduction of “Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women Against Themselves,” an Andrea Dworkin quote.

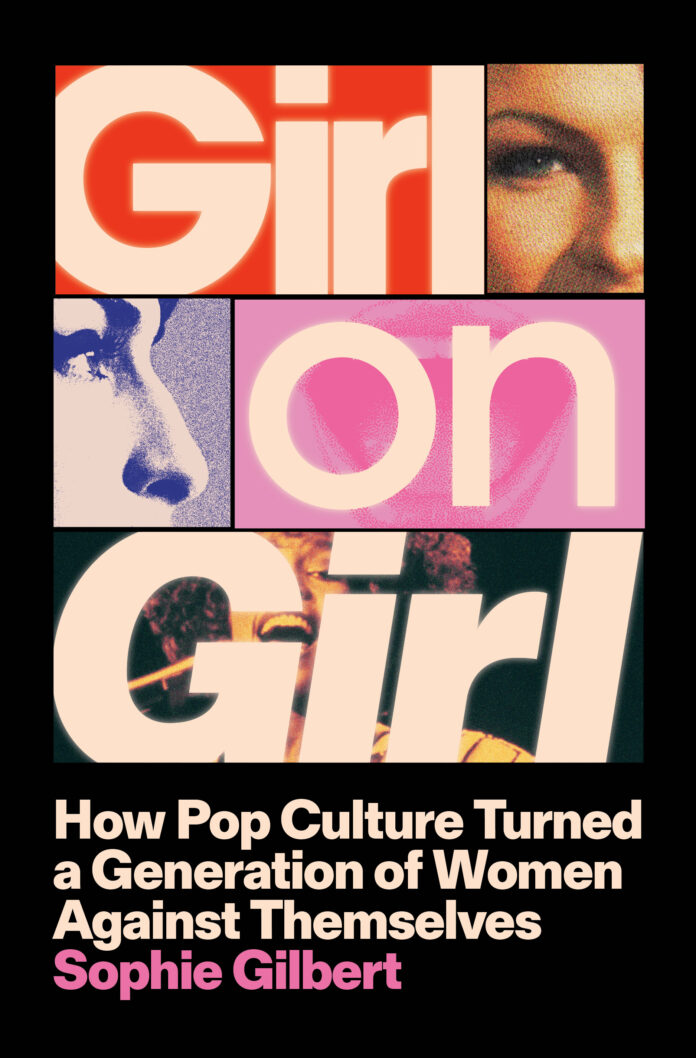

The quote, “woman is not born: she is made,” does not allude to Dworkin’s anti-sex/anti-porn ideologies that made her so notorious. Instead, the quote nods to social constructionism. The theory that gender, like sexuality and sexual orientation, is not fixed at birth, but taught and practiced, as hardwired as a sense of style might be. “Girl on Girl” is a massive project. In it, Sophie Gilbert, finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Criticism and staff writer for The Atlantic, reappraises the pop culture zeitgeist at the turn of the century to analyze how it affected girls staring down the new millennium, girls who are now grown millennial women.

The word “reappraise” is not without intention. For decades pop culture has valued women based on their ability to conform to a narrow standard of womanhood – the plastic ladies of reality TV, nearly nude heroin-chic models, and provocative virginal teenage girls. In “Girl on Girl,” Gilbert argues that young women were not born to see themselves as objects, trapped in these constructions, but informed of their worth by a booming pop culture industry imbued with the misogynist tropes, images, and aesthetics of pornography.

In her research, Gilbert found that porn was everywhere in the 1990s. Part of this surge, as she explains, was created by the aftermath of the AIDS crisis. The AIDS crisis brought sex, who is having it and with whom, into mainstream discourse. In pop culture, Madonna released her coffee table book, “Sex,” and everyone watched Anita Hill testify in the Senate about sexual harassment by then Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. History set the tone for a decade of show-all sex that sold, sold, sold.

“Girl On Girl” hovers around the term “post feminism,” an idea coined in the early eighties that feminism was no longer necessary. Gilbert begins with a look at the music industry. Influential for its easy dissemination of messaging to the masses, the music industry transformed feminism from a political movement, into post feminist blow out sale. Beginning in the early 90s as a response to a hyper masculinist punk scene, three Olympia, WA punk bands, Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and Heavens to Betsy, created the Riot Grrrl movement. In the first Bikini Kill zine, an anti-establishment method of sharing information, Tobi Vail, Bikini Kill’s drummer, coined the term Girl Power. For Riot Grrrl, Girl Power was a slogan intent on seeing girls support each other. It made demands. It had real power. Within a few years, the male-managed Spice Girls made the phrase globally renowned. Not for its political potency as Riot Grrrl intended, but for its ability to sell teen girls ephemeral toys. Lipsticks, hairbrushes, and Polaroid cameras adorned with the label “empowerment,” branded with Spice Girls pictures, became the brave new world of post feminism: convincing girls and women that independence and equality came through spending money.

The shift from a collective women’s movement to an era of regression repeated relentlessly in the nineties. This pattern of progress, to varied degrees of effectiveness, followed by a swift and often brutal backlash, Gilbert explains, should help us understand why we are currently in a period of cultural regression. A moment in which the manosphere led Donald Trump back into the white house, only a few years after the #MeToo Movement plucked habitual sexual offenders from their corner offices.

The music industry, in addition to selling out feminism, adopted the profitable imagery of pornography. The early nineties were incredibly full of women artists singing about oppression and desire, but they were replaced by the more controllable teenage girls. By 1999, women had been sidelined entirely. The 99’ Woodstock music festival ended with massive reports of sexual assault, some of which took place in mosh pits. A cover of Q magazine even pictured PJ Harvey, Bjork, and Tori Amos with the title: “Hips. Lips. Tits. Power.” Snoop Dogg’s brief and mysterious stint on the L-Word cannot erase the fact that he walked into the MTV Video Awards in 2003 with two women on leashes by his side. Gilbert goes on to list an abundance of pornographic music videos, videos that devolved into real physical violence against women.

As soon as the music industry started profiting off porn, in all its brazen shaven manifestations, the fashion, film, and television industries wanted a piece. Reality television debuted on MTV in 1992 with the show The Real World. The success of which created huge demand for more, cheaper shows that would lure audiences in with no regard for quality. The result was a downward spiral for more degrading reality television, which is how we got shows like Who Wants To Marry A Millionaire?, The Housewives franchise, and eventually, The Bachelor. All of which depict women in a nineteenth century frame, where success equals catering to male desire. Reality television also cultivates a singular, highly stylized, white, middle class, thin, feminine, and sexy caricature of women. A blueprint set by pornography.

Gilbert makes plenty of room for relief in pop culture’s representation of women in the aughts. Artists like MC-Lyte, Janet Jackson, and Queen Latifa’s song “U.N.I.T.Y” deserve a revisist, as do movies like The Breakfast Club and 16 Candles. But they were heavily outnumbered by a male dominated rap scene and movies obsessed with teenage girls’ virginities: Lolita, American Pie, Wild Things, and Kids. Film in particular, Gilbert argues, created an entire generation who internalized toxic ideologies about men and women’s sexuality. Girls were gatekeepers of sex who needed to be convinced, rather than enticed, into having it. In other words, girls were the enemy of male desire. The result? Young murderous white young men who kill girls who refuse to sleep with them, as if sex is something they are entitled to. An idea plainly perpetuated in nineties films.

In Chapter six, at the book’s peak, Gilbert’s investigation into pornography seems like a sado-masochist endeavor itself. The chapter is stuff of nightmares. It is also the reality of pornography. In a post 9/11 world obsessed with revenge, Gilbert eloquently says porn “tested the limits of what men could do to women as entertainment while cameras rolled.” Porn emerges as a mirror to society’s view of women as loathsome leaky sex objects who should do their best to conform, from shaving their bodies, pits to toes, to becoming unrecognizable via plastic surgeries, as to render their own degradation more pleasurable to watch.

After the turn of the century, it became clear that the world had deeply internalized porn as an art form. It peaked with the release of the school-girl porn trope in Brittany Spears’ “Baby One More Time” music video. And fell down a very dark hole with the photos of the Abu Ghraib torture of Iraqi prisoners by members of the US military.

The latter half of the book examines the consequences of a culture dominated by pornography and over exposure. “Every single cultural message Americans absorbed during the decades leading to the [2016 Presidential Election] was enshrining the idea that women fundamentally lacked the qualities required to gain and exercise authority: intelligence, morality, dignity.” For Hilary Clinton, that meant losing the election to Donald Trump. For celebrities, that means Lindsay Lohan goes to rehab, Anna Nicole Smith dies of an overdose (leaving behind a fridge full of Slim Fasts), Britney Spears shaves her head in front of paparazzi, Amy Winehouse and Whitney Houston die from overdose too. The celebrities left seemingly unscathed are the ones who Gilbert labels “walking billboards”: The Kardashians and their ringleader, Kim Kardashian, made famous her sex-tape and trendy body modification. For the rest of us, this means navigating a world entrenched in misogyny, influenced heavily by what we have watched, read, and seen.

Gilbert says she is not as “anti-porn” to the militancy Dworkin was. She does not even mention Dworkin beyond the introduction, but the depth in which porn entrenched itself into our pop culture, and the consequences it has held, suggests perhaps we all should be. Misogyny is as rampant as ever. Roe v. Wade is gone and the White House is enmeshed with the cast of reality television flops with porn stars on the fringes.

Western pop culture has been waging a war against women, reinforcing their silence, since the age of The Odyssey, when, as Gilbert alludes to in the conclusion, Telemachus tells his mother to shut up and go to her room. What’s a girl to do? Well, there is reason for hope. Bikini Kill plays sold out 30th anniversary concerts, screaming their anthem “Rebel Girl” on the Stephen Colbert Show, and movies and TV shows like Babygirl, The Last Summer, and Insecure give female sexuality the complex depictions it deserves. Gilbert offers a solution too. Stories, new stories, have the potential to liberate pop culture from patriarchy and misogyny. In return, women can rewrite their concepts of sexuality, pleasure, and place beyond what the aughts tried to teach them. To quote the turn of the century musical RENT about a queer friend group navigating AIDS and poverty: “The opposite of war isn’t peace, it’s creation.” In a world where AI spits our own biases back at us, who will heed Sophie Gilbert’s call and create a new story for women?