In the silence between materials, Wuchao Feng makes language. In her work, the salt crystals crunch underfoot, uneven pearls spell aphasic fragments, and a red heap dissolves into migration trails. Each of the elements gestures toward a poetics of the inarticulable. If her earlier work offered a visual grammar of fluid identity, her most recent explorations in salt and pearl have shifted toward a dense, embodied metaphysics.

Wuchao was born in the port city of Ningbo and is now based in London. Her work is inspired by the sentiment of a dual inheritance. Dilution (2020) is a long-evolving performance and installation project that maps a symbolic topography of identity through the dispersal of sea salt. She treats salt not only as a substance but as semiotic residue, each crystalline trace a metaphor for the disarticulation of the self in transit. The female body becomes a non-fixed and fluent salt body.

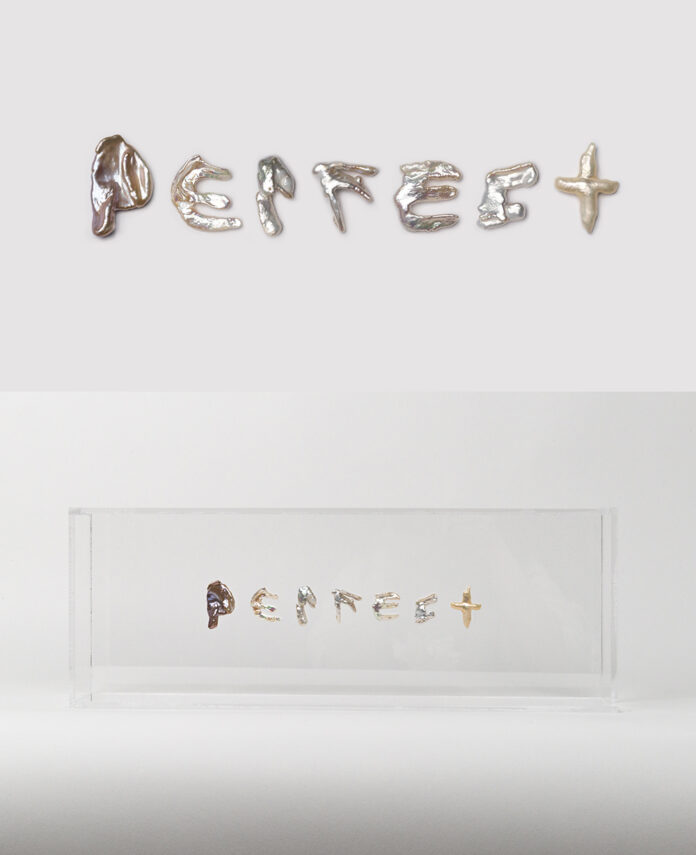

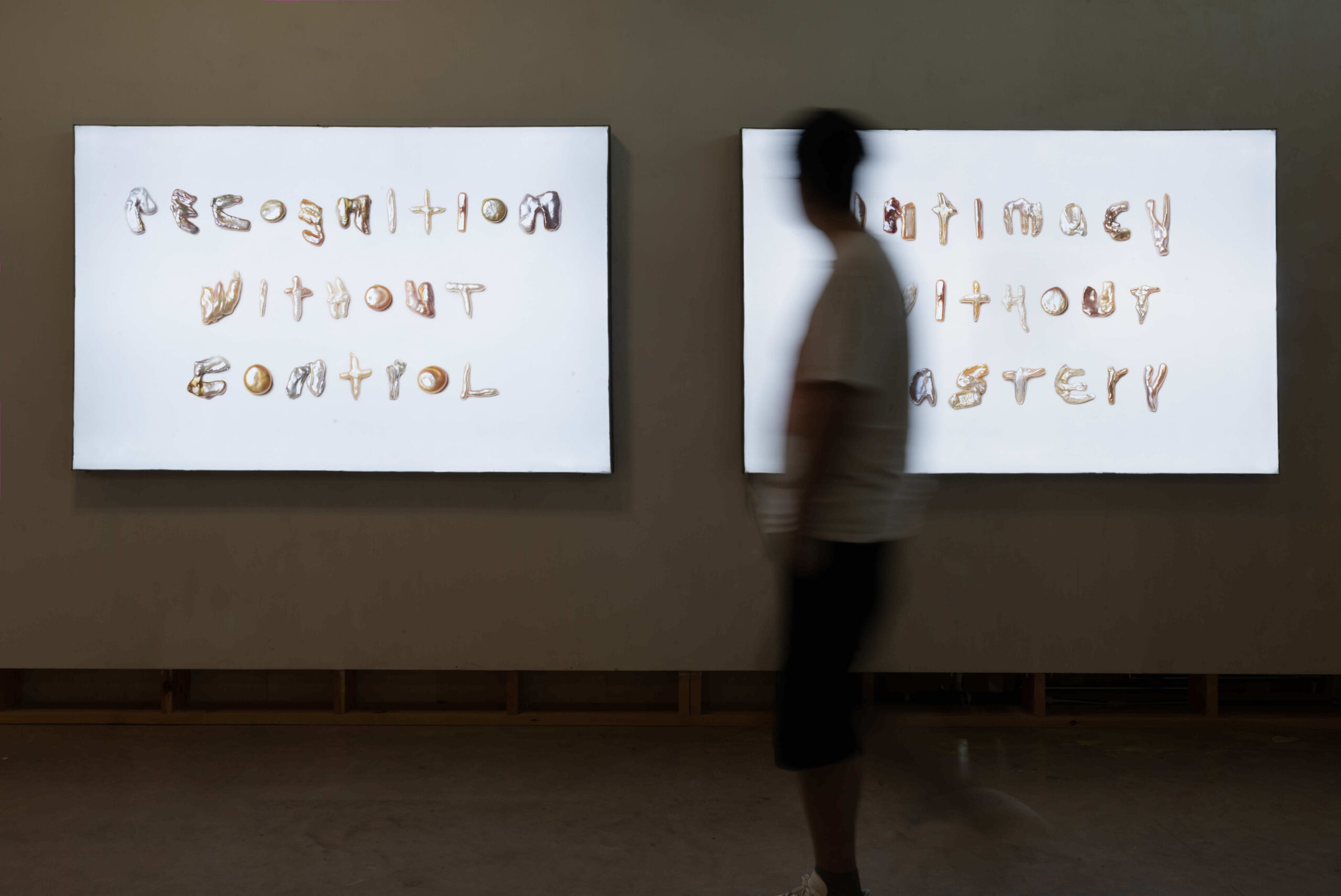

The image of the scar and the healing wound haunt Wuchao’s Pearl series explicitly. Unlike the salt which liquefies with time, the pearls calcify around intrusion. This metaphorical symbol becomes the heart of her formal inquiry. Pearls of Wisdom (2023) uses different shapes of pearls to form words and phrases. In the delicately represented pearls, one reads trauma not as rupture but as the beginning of formation.

Where salt dispersed the subject, pearls insist on coherence, but a coherence born through resistance. These are not metaphors of feminine delicacy but of a kind of mineralized endurance. The feminist logic lies in the body, absorbing its violence and metabolizing it into form. Drawing from Elaine Scarry and Judith Butler, the artist understands the body not only as a site of injury but as a site of inscription. These alphabet pearls do not just spell, they scar and shimmer.

The way Wuchao situates these processes in a transcultural method is striking. The salt, harvested from Ningbo’s traditional salt fields, references histories of labor and survival specific to China’s coastal economies. The pearls are sourced from flawed industrial batches, symbolizing both the feminized labor of pearl cultivation and the global circuits through which value is assigned to aesthetic purity. She refuses to aestheticize them into perfection, instead, she materializes cultural specificity through the lens of the personal and gender-related trauma.

Language becomes unstable under her hands. Not just because it is formed from irregular pearls, but because the words themselves stutter across meaning. She is not interested in clarity but in the failures of translation: between cultures, between bodies, between pain and speech. There is no neutral tongue here. There is only the muteness of affect, slowly reconstituted into something almost, but not quite speakable yet.

In conversation, the artist has spoken of her own struggles with expression across languages—Mandarin, English, dialects, and the voiceless syntax of trauma. This multiplicity is not resolved in her work but embraced as the condition of its genesis. Like a poem composed from borrowed alphabets, her practice reclaims the right to speak with brokenness.

It is within this fragmentary ethos that her engagement with feminist and transcultural discourse becomes most potent. Her salt trails crisscross, interrupt, and disappear—much like the diasporic experiences that inform them. And her pearls do not align neatly into syntactical order but drift into loose constellations—suggesting not mastery of language, but intimate cohabitation with its limits.

When some artists construct worlds, Wuchao reconstructs injuries. Her installations are not landscapes but woundscapes. They consist of pain, memory, and place colliding. Yet they are never solely about her. In refraining from autobiographical legibility, she allows her viewers to enter these landscapes not as voyeurs but as witnesses.

In an era when identity is often weaponized as a static declaration, Wuchao offers something riskier: an aesthetic of becoming, of slow accumulation, of intimate estrangement. Through her work, trauma is neither fetishized nor resolved. It is translated, haltingly, into a shared visual syntax—one that, like all good metaphors, both reveals and refuses.

She continues her practice within the context of the UK’s art world, especially during her residency at the Bomb Factory Art Foundation. Wuchao’s work promises to deepen these lines of inquiry. Her commitment to biomaterial research and feminist methodologies speaks not only to personal evolution but to a broader collective reckoning with how we remember, how we endure, and how we speak. Wuchao Feng does not ask us to understand. She asks us to listen—to what language cannot hold, but materials can.