At the end of Ishiro Honda’s Godzilla (1954), a forlorn scientist named Dr. Serizawa ventures to the bottom of Tokyo Bay and unleashes the Oxygen Destroyer, a doomsday machine he unwittingly invented and has heretofore kept secret from the world. While fearful that “the politicians of the world” will turn his discovery into the latest Cold War superweapon, the scientist has agreed to use it just once. A monster called Godzilla has burned Tokyo to the ground, and Serizawa’s invention is the only thing that might stop the menace. After activating his device, he cuts his air and support lines—ensuring the Oxygen Destroyer is never remade—and Godzilla is disintegrated first into a skeleton and then into nothing. In the aftermath, another scientist, played by that wonderful actor Takashi Shimura, issues a warning. Believing Godzilla to have been awakened by H-bomb tests in the Pacific, he states, “If nuclear testing continues, then someday, somewhere in the world, another Godzilla may appear.”

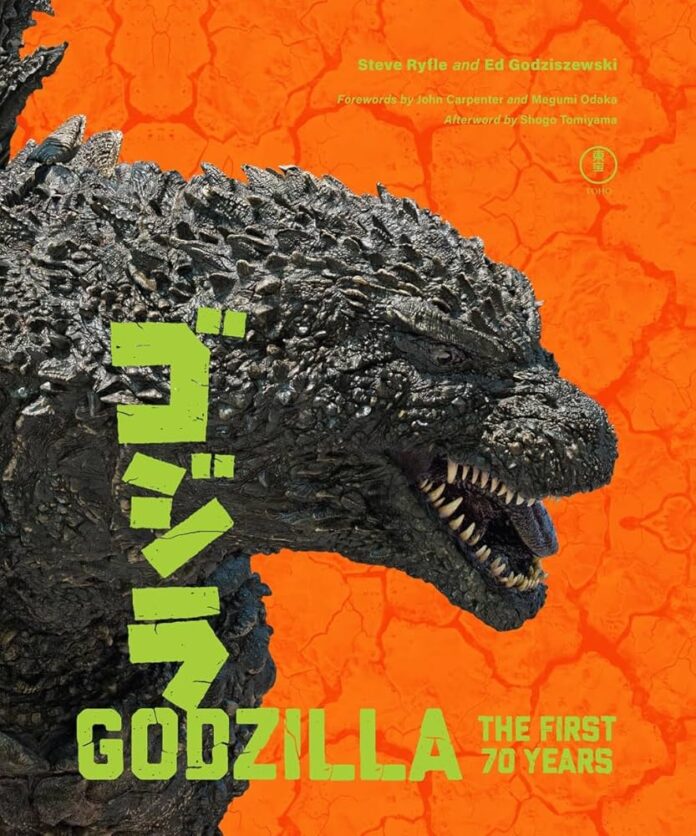

As is documented in Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski’s new book Godzilla: The First 70 Years, screenwriter Takeo Murata wrote this monologue not “thinking about a sequel.” Nevertheless, the movie’s impressive turnout (9.6 million in attendance) paved the way to a quick follow-up—Motoyoshi Oda’s Godzilla Raids Again (1955)—and, beginning in the ‘60s, more pictures starring the monster. In the course of its seven-decade history, Godzilla has appeared in entries ranging from witty satires to anti-pollution polemics; the character has been a villain, an ally of convenience, and a bona fide superhero. It has found admirers worldwide, including among Hollywood talents such as Guillermo del Toro. And in 2024, Takashi Yamazaki’s Godzilla Minus One (2023) took home the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects. Godzilla holds the record for the longest-running film franchise; such a rich and complex legacy warrants a detailed study, which now arrives in the form of Ryfle and Godziszewski’s tome.

Godzilla: The First 70 Years is the latest contribution its authors have made to English language knowledge about the movies under discussion. Both separately wrote info-packed books in the 1990s, and together they penned the 2017 biography Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa. And that is to say nothing of their numerous articles, audio commentaries, interviews, etc. that have afforded western moviegoers a deeper appreciation for the films and the people behind them. Now comes this 432-page volume covering the Japanese series from its inception to the present day, chock-full of research and gorgeous behind-the-scenes photographs.

The book opens with a pair of introductions: the first by American filmmaker (and known fan of the series) John Carpenter, the second by Japanese actress Megumi Odaka, who played the psychic Miki Saegusa in six Godzilla movies between 1989-1995. Odaka’s introduction is delightfully substantial, consuming the better part of two pages as she recounts her experiences and provides insight into the men who directed her. (“[Takao] Okawara’s style was very masculine, but his work also reminded me that women’s characters are equally important.”) From here, Ryfle and Godziszewski group the movies into five sections and take us through the history one title at a time. This easy-to-navigate approach accommodates a variety of reading choices: one can read straight to the end or open a particular chapter to learn about a specific movie. As always, the authors do a wonderful job articulating the challenges endured by the filmmakers and delivering fantastic information. (Among the highlights is an unfilmed alternate denouement for 1962’s King Kong vs. Godzilla—completely unrelated to the movie’s infamous “double ending” myth.)

In what marks a departure from their previous writings, Ryfle and Godziszewski stray from making critical comments—not a flaw per se, merely a difference. While I admittedly missed the duo’s flair for analysis, the research and the plethora of quotes from cast and crew members make for an informative read—one that has helped fill gaps in previous genre studies. The late Kensho Yamashita, for instance, directed just one entry, 1994’s Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla, and his few English language interviews were conducted more than three decades ago. Thanks to this book, we now have access to numerous translated statements from Yamashita and gain a more complete understanding of his goals when making the ‘94 movie. Some anecdotes might prove surprising (suit actor Haruo Nakajima preferred Godzilla Raids Again to its predecessor “at least for my acting”) while others touch the heart: Momoko Kochi, who played the heroine in the original movie, recalls that scriptwriter Kazuki Omori wanted her to reprise the part in Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995) “no matter what.”

In tackling a franchise as complex as Godzilla’s, Ryfle and Godziszewski appropriately dedicate numerous sidebars and sub-chapters to topics such as urban legends, alternate cuts, and the process of building monster suits. The book also features a pair of guest essays by biographer Erik Homenick and set reporter Norman England. Homenick has spent years documenting the life and works of composer Akira Ifukube, and here delivers an erudite piece on the 1954 Godzilla score. And England, who covered the Millennium Godzilla movies (1999-2004) for various publications, offers a personal account of still photographer Takashi Nakao, one of the unsung heroes of Godzilla lore, based on his experiences interacting with him on Shusuke Kaneko’s Godzilla, Mothra, King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-out Attack (2001). (My correspondence with England confirmed that several of the book’s making-of photos for the Millennium films were taken by him and are appearing in print for the first time.)

On the negative side, the book’s copy would’ve benefited from an additional round of editing. Within its pages exist the occasional typo (a misspelling of director Atsushi Takahashi’s name), grammatical error (“an Godzilla attraction” [sic]), and incorrect word choice (Dr. Serizawa is described as Momoko Kochi’s “fiancée”). There are also a few instances of sloppy writing. When director Masaaki Tezuka remembers receiving the offer to helm Godzilla vs. Megaguirus (2000), he’s quoted: “I discussed it with my wife and decided to accept.” A nice anecdote that’s promptly—in the very next line—followed by a third-person description repeating that same information with similar wording: “[E]ven when offered the opportunity to direct […] he consulted his wife before accepting.”

Lastly, while Godzilla: The First 70 Years is a wealth of research regarding the Japanese movies, some consumers might be disappointed by the lack of coverage for the series’s Hollywood remakes. Whatever one’s feelings about Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla (1998) or the ongoing MonsterVerse saga from Legendary Pictures, they are part of the franchise—and integral ones at that, having more than once influenced the course of the Japanese series. Ryfle and Godziszewski fleetingly note their impact, but it’s unfortunate the American films do not receive the full-fledged treatment granted to their Japanese counterparts.

All in all, though, Godzilla: The First 70 Years marks another splendid achievement from the finest English-speaking historians to tackle the Japanese monster. In many ways, this book represents the sort of project I’ve wanted from these writers for some time. Steve Ryfle’s Japan’s Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of “The Big G” and Ed Godziszewski’s The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Godzilla remain go-to texts for genre enthusiasts, and for years I’ve hoped for updated editions wherein they documented their knowledge of the post-’90s movies. This new tome, available from Abrams Books, has answered that call and will be of tremendous value to casual and dedicated readers alike. It is also a must-own for contemporary researchers, those who’ve followed in the authors’ footsteps in preserving the legacy of these movies and the artists who made them.