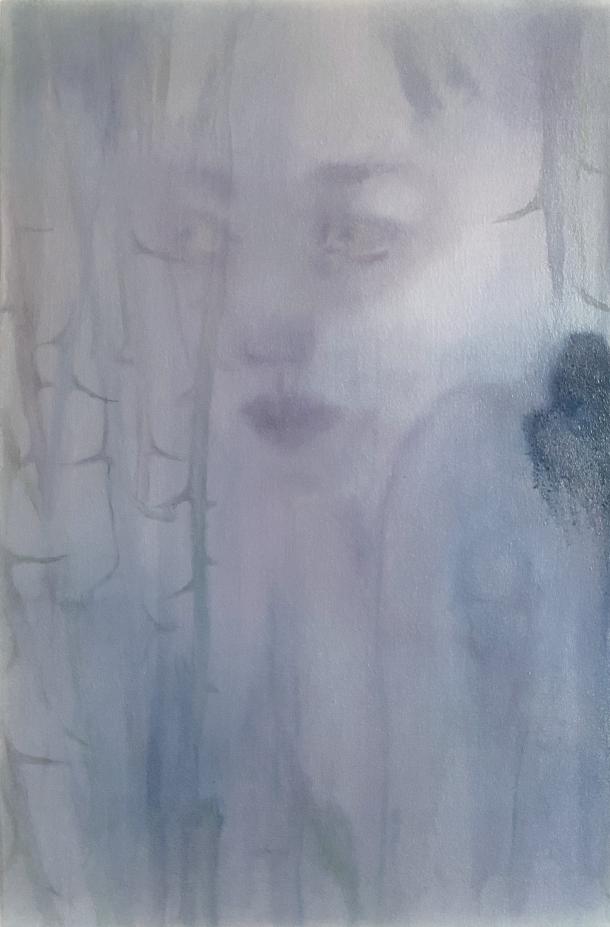

It resembles a landform or a patch of soil; the scene is abstract, humid, plain, and dark. In Jie Zhang’s painting Dense Forest II (Figure 2), a female figure moves through a jungle bristling with thorns. The atmosphere is dreamy and imaginary, yet it evokes a real place she may have once experienced.

It is difficult to categorise this work solely as a landscape painting, whether abstract or realistic. Jie Zhang considers herself first a poet, then a painter. She was born in China during a period when many parents left their hometowns to work elsewhere, leaving their children in the care of elders. She spent years living with her grandparents in their garden cottage and moved homes multiple times during her childhood.

Nourished by the calm of natural life, Jie developed a heightened sensitivity to her sense of belonging and personal identity. This awareness once became a source of conflict, as she struggled to reconcile the demands of society with the needs of the individual spirit. By the age of twenty, these questions had evolved into both a personal crisis and a philosophical exploration. She asked why the world is hierarchical, why the powerful receive praise, respect, and privilege while the vulnerable endure harm and discrimination. Why do spiritual needs often seem opposed to physical requirements? We all require the same essentials, yet some gain more while others lose. Why should social identities determine who we are, rather than our own qualities and inner truths?

Jie Zhang’s work, including Dense Forest series, reflects this philosophical and emotional inquiry. Her paintings are not only visual landscapes but also poetic explorations of memory, identity, and human experience. The tension between abstraction and realism mirrors the tension she has long observed between society’s structures and the individual spirit. Through her art, she invites the viewer to engage with these questions, experiencing both the beauty and the complexity of her imagined yet deeply personal worlds.

“I wanted to prove the universality of the principle of crabs in the bucket.

I wanted to prove the impossibility of Utopia theoretically, in other words, it means buddhahood.

I wanted to prove that life force/sex/power, love/cruelty are the same thing.

I wanted to prove that the food chain is class is nature is equality.

I guess awareness is everywhere is empty is the wave.

I guess duality is the function of awareness, is one the whole is every one whole, not guess.

I think I know the truth, it is where my vulnerability comes from.”

From an early age, Jie observed social class and inequality within her family and among her relatives, as well as in the relationship between humans and other species. These observations inspired her early writing, whether in the form of poetry or casual diary entries.

She sought ways to transcend the limitations imposed by social identity and the unchangeable core of the self, what she later referred to in her artworks as the “spiritual home.” To explore this, she turned to Buddhism, literature, philosophy, and even natural sciences, drawing inspiration from thinkers such as Richard Feynman and Erwin Schrödinger. Many of her poems from this period explored themes of self-deconstruction and the cycles of life.

Since 2015, Jie has brought these insights into her artistic exploration. Her inner landscapes, combining local landforms and memories, became a central theme closely tied to what she calls her “spiritual home.” Rather than focusing on specific people or places, she drew sustenance from the garden of her childhood, which continued to nourish her creativity.

For Jie, blossoming is every flower’s mission, regardless of how harsh the conditions. From her grandparents, she learned the qualities of being a creator, a giver and a carer, values that continue to shape her work.

From 2021 to the present, she has incorporated fragments of literary texts and worldviews shaped by her upbringing into her new works. She is constructing a kind of garden through her art, not merely revisiting the past, but holding together these diverse forms of experience. Her work acts as a vessel, transcending the linear flow of time and the boundaries between disciplines.

The concept of “Duality” also informs her practice. Borrowed from physics, it describes how a single thing can possess opposing sides or appear in different states depending on the observer. The sensible world, she suggests, is an accumulation of this law. “When I reached this point, I began to understand everything,” she explains, reflecting on the clarity this perspective brings to both her life and her art.

The project, titled Dense Forest, comprises two parts and explores a range of contrasts. From what I can discern, it plays with shade and light, memories and reality, thorns and beauty, savageness and tenderness. These contrasts are articulated across multiple dimensions: in her handling of paint, with dense, textured brushstrokes juxtaposed against smoother, more ethereal surfaces; in her compositional choices, where chaotic natural forms coexist with deliberate spatial organisation; and in her visual language, which balances abstraction with glimpses of figurative elements. Literary and philosophical metaphors are woven into the work, creating layers that invite both visual and intellectual engagement. At the perceptual level, the paintings evoke tactile and atmospheric qualities, humidity, darkness, and weight, while suggesting ideas about the universe, cycles of life, and human consciousness. Another work, Garden, approaches similar themes, emphasising cultivation, growth, and the nurturing aspects of memory and experience.

At its core, the project is about repetition. Jie views everything as formed from the same fundamental elements, which are separated and reorganised continuously. This principle, evident in her poems as well as her visual practice, is informed by reflections on Buddhism and physics. In her view, nothing is truly different, and there is no need for it to be. In Garden, she repeatedly arranges similar elements within a conceptual vessel, allowing motifs to recur, overlap, and resonate. Repetition becomes a method of living, a way to engage with time, memory, and presence. One might think of Sisyphus, though without negative connotations; it is a recognition of persistence, effort, and the meditative rhythm of creation.

Her method embodies this philosophy. Working with a restrained palette, she mixes colours repeatedly to achieve subtle tonal variations and harmonious gradations. Textural effects are carefully modulated, producing surfaces that feel simultaneously fragile and resilient. The result evokes particular landscapes from memory, abstract prospects, philosophical reflections, and structures reminiscent of prose or poetry. Her work requires engagement beyond the visual, inviting the viewer to contemplate cycles, correspondences, and the interplay between perception and imagination. Although Jie was trained in strict classical painting techniques from a young age, she deliberately moves beyond these conventions, creating a highly individual style that blends discipline with poetic freedom, precision with emotional resonance.

Through works such as Dense Forest and Garden, Jie Zhang embraces the ongoing process of creation, where repetition, duality, and memory converge. Her art does not offer a final answer but provides a space for contemplation, reflecting both her philosophical inquiry and lived experience. Each stage of her practice is a continuation, an exploration that balances discipline with poetic freedom, precision with emotional resonance, and abstraction with glimpses of reality. In this way, her work invites the viewer to engage deeply, experiencing the complexity, fragility, and richness of her imagined yet profoundly personal worlds.