Silence is the space preceding language, and that space — between one tongue and another, between gesture and thought — is inhabited by Yuying Song. Born in 1998 in Shandong and currently residing in London, Song is a wanderer in terms of medium and continent. Her work is both poetry and installation, both performance and silence. Song uses not only words but also materials (tracing paper, powder, cosmetics, breath). As she touches everything, the distinction between writing and being dissolves. Song’s art occurs at the site of disintegration of identity. We are in a world in which the boundaries of East/West, male/female, etc., continue to define our existence. Thus, Song constructs sites of porousness, incompleteness, and life.

Song describes herself as a wanderer, and this image captures her artistic practice well. There is a restlessness in her process, along with a refusal to be confined by the boundaries of nationality, gender, or even language. Her poems inhabit multiple languages at once. The presence of Mandarin within English runs through her work like an undercurrent of sound and rhythm, subtly shifting meaning and sense. When a poet moves between languages, meaning changes and transforms, giving rise to a new kind of voice, one that carries traces of both languages and reveals something uniquely her own.

Song started performing in Beijing’s performance scene around 2020 with Masked Soliloquy, and then continued with 22 ‘She’ and I in 2021. Early performances demonstrated how Song could merge theatre and text in ways that felt visceral. In those early works, the voice was expressed through the body — blindfolded, shaking, intentionally so, as she delivered her spoken words. Performance wasn’t spectacle; it was endurance. And yet, it was simultaneously being visible and invisible. Though Song’s practice has evolved significantly since those early days, some fundamental elements continue: the body as language, and the word as skin. Many of her installations represent fragments of lived experience — echoes of voices, impressions of touch, the faint smell of makeup (foundation). While everything speaks softly, nothing is passive.

Chinadoll, Song’s 2024 installation, demonstrates perhaps the most fragile intensity of her work. On first appearance, Chinadoll is ethereal. Sheets of transparent tracing paper hang in the air, floating between breaths, covered in layers of makeup (powder, blush, shimmer), each applied directly to the tracing paper. Across the delicate sheets, words are printed onto the tracing paper itself, faint yet precise. You have to lean in to read them. When you do that, it begins to transform. The title of the installation itself — Chinadoll — holds multiple meanings. “China” can mean both delicate and fragile (porcelain), and “China” can also refer to homeland. The word carries meanings that relate to both fragility and disintegration.

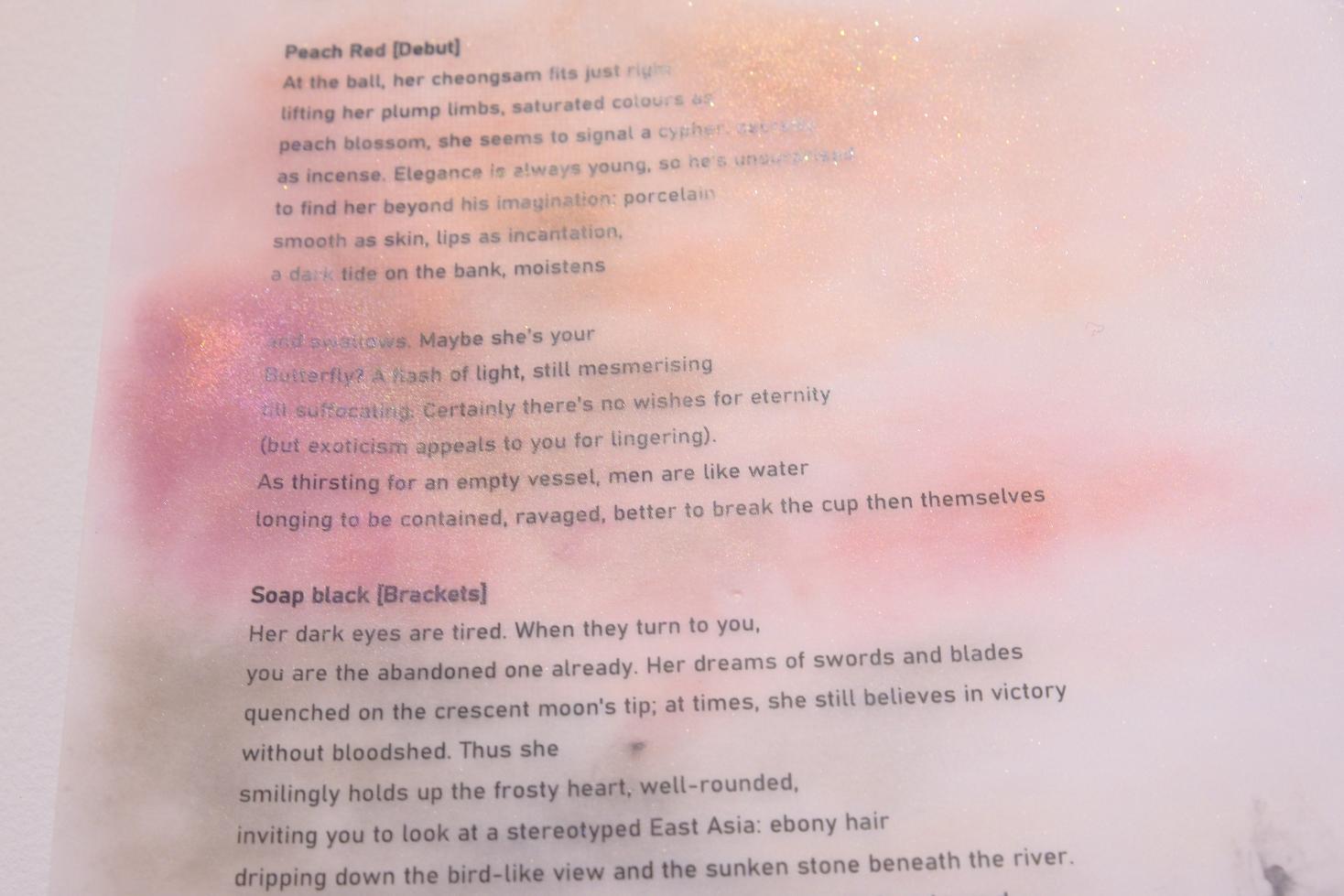

Song uses her sequence of poems — Peach Red, Soap Black, Jade White, Indigo — to dismantle the mythology of the Oriental woman: that decorative and obedient image of women that the West admired and still fetishizes today. Initially, the poems are enticing, moving with elegance: “her cheongsam fits just right… smooth as skin, lips like an incantation.” As the poems proceed, however, the language shifts. The surface breaks down. What begins as desire becomes suffocating; what began as beautiful becomes an instrument of violence. “Disassembling bursts of quick darts from smooth wholeness: shattering is such a powerful and valiant force.” she writes. Fragility gives way to defiance. The residual cosmetic material from the makeup on the tracing paper serves as evidence of the physicality of display. The dust of blush, the fingerprints, the fading of words at the edges — all are byproducts of both artifice and reality. Song understands that the surface of a subject is always politically charged.

What we refer to as delicate is often the product of an act of power. In Chinadoll, the ritualistic nature of feminine performance (make-up, posture, dress), while not mocked or dismissed, is reclaimed and transformed. What appears fragile becomes violently destructive. When standing before the panels, there is a tension between visibility and disappearance. The poems shine but will not stay still. They exist in that moment of flickering — the moment before the collapse of recognition into stereotype. You look, and you are looked back at.

In many of Song’s recent performances in London, she has incorporated sound into her work — her voice whispering phrases that hover between sense and echo. The overall effect is haunting. It is as if you are standing inside someone’s memories, or beneath someone’s skin. While Chinadoll examines the gaze from without, Song’s ongoing She series examines the gaze from within. It is the most personal and possibly the most demanding of her works. Spanning from 2021 to the present, She — She I to She IV — presents four aspects of womanhood: pain, defiance, tenderness, rebirth.

A key part of Song’s ability to tell a young girl’s trauma with such devastation is her reluctance to dramatise what is already unbearable. The horror of sexual assault is not in the drama or the sensationalism; it is in the quiet. She (II) is colder than She (I). It is a portrait of the loneliness of Beijing nightlife through eyes that are exhausted. It snows “step-by-step,” the city becomes white, and the speaker wonders how to appear natural while surrounded by men whose smiles hide their expectations and demands. It is a poem of survival, written in flashes of light.

Then there is She (III) — the explosion of the text into a chant: “Exist. Exist. Exist.” This is a feminist song, angry and alive. It is a rally, a spell, a heartbeat. “Sister, Mother, Daughter — exist.” These words beat like a drum.

In She (IV), the cycle has turned back on itself. Two women have met; they are both mythic and mortal. Their bodies come together and reflect one another. Anger and tenderness are intertwined. “Her anger is my anger,” Song writes, “the duet of mirrors.” The poem ends with the kind of silence that seems eternal.

These works installed in the gallery refuse to be spectacular. Panels hang slightly away from the walls, held by thin nails, partially hovering. The space between each panel is carefully measured; it is breathing space. A tablet or speaker quietly plays Song’s voice simply reading her poems, guiding the audience to settle into the space and experience the poems more vividly.

However, when the performance takes place live, the tone of the works changes again. In 22 ‘She’ and I, Song appeared blindfolded, holding a book, and moved through the darkened space using her sense of touch. The audience watched Song move through the darkness; hesitant at first, then confident. Each movement Song made became a metaphor for how women move through violence, through expectation, and through the unlit corridors of memory.

For Song, performance becomes testimony, a practice of dwelling within vulnerability until it turns into strength. Her politics are lived, not proclaimed.

As a bilingual artist, Song uses her two languages as allies rather than as opposing forces. The tension between them creates meaning. For Song, translation is not about clarity; it is about survival. It is about carrying the same emotion or idea across different skin tones, knowing that something will always be lost — and that the loss itself can be beautiful.

She refers to herself as a wanderer, but this is not about physical displacement. It is about motion. It is about constant transformation. What makes Song’s work relevant today is its resistance to arriving at a stable identity. In an era obsessed with certainty, Song insists upon fluidity.

Song’s use of materials — cosmetics, tracing paper, voice — brings her work into the present moment. Her art recalls the quiet force of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s writing, the tactile poetry of Ann Hamilton, but her materials root her in the now. Song is developing a new language for intimacy that separates neither tenderness nor critique.

There is also a curatorial intelligence behind how Song arranges space. The rhythm of the space between panels, the weight of the silence, the echo of Song’s voice in a small room — each decision is choreographed to create empathy, not pity. Song invites you into her world — but never allows you to look away.