In a December 1992 interview with Cult Movies journalist David Milner, Japanese film director Ishiro Honda—the maker of such classics as Godzilla (1954), Rodan (1956), and Matango (1963)—recalled the process through which Toho, the studio he’d worked for, developed its science fiction movies. He gave, as an example, the genesis of his 1961 film Mothra: “The planning department went around gathering ideas; [three] novelists were then commissioned to write a story about a big moth and […] tiny fairies; the story was published in a special edition of Shūkan Asahi [a weekly publication]; and shortly afterward Mr. [Shinichi] Sekizawa wrote a script based on their work.”* Shooting commenced with Honda supervising the live-action footage and effects virtuoso Eiji Tsuburaya handling the creature scenes. The result was one of Toho’s crowning genre achievements: an extravagant fantasy rife with spectacle and supplemented by an infectious sense of humor.

Mothra became the tenth-highest-grossing Japanese feature of 1961 and found further success abroad via its American distributor, Columbia Pictures. A mere three years passed until Toho revived the monster in Mothra vs. Godzilla and then again, this time just months later, in Ghidorah the Three-headed Monster. The ensuing decades witnessed a myriad of further adventures featuring the giant moth, among them a 1992 rematch with Godzilla, a late-‘90s trilogy aimed at kids, and an entry in Legendary Pictures’s ongoing MonsterVerse saga. (Nearly every plot highlighted Mothra’s guardianship over the fairies.) And yet, the novella which gave this character and its protectorates their actual debut has remained unavailable—or at least indecipherable—to those not proficient in Japanese.

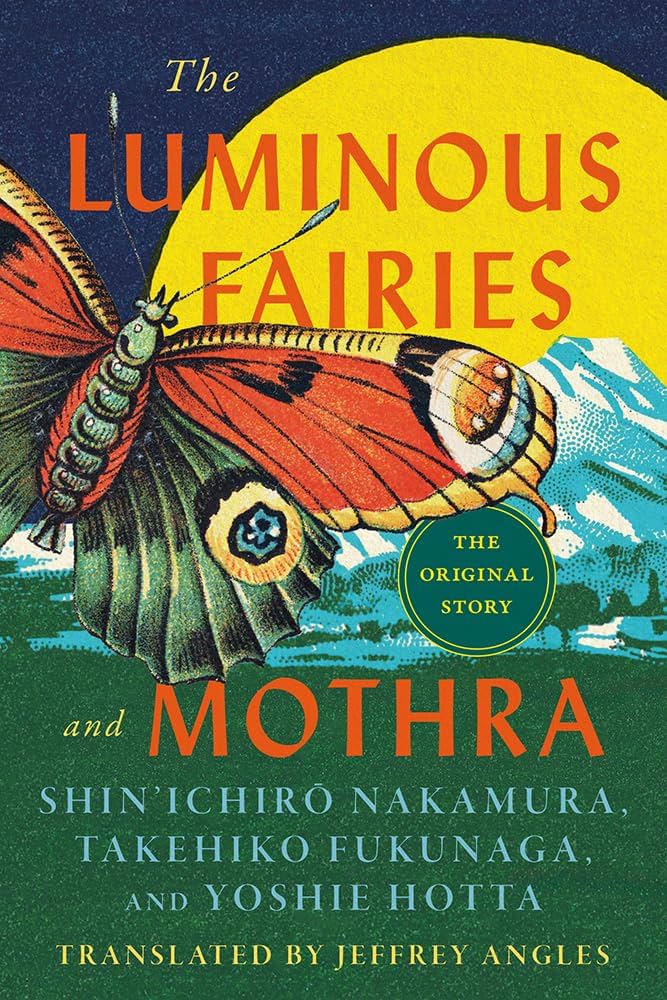

But now The Luminous Fairies and Mothra has been converted into English thanks to University of Minnesota Press and translator Jeffrey Angles, the team previously behind Shigeru Kayama’s Godzilla and Godzilla Raids Again. This new book, in a sense, is more significant. Although Kayama had written foundational stories for Godzilla and Motoyoshi Oda’s Godzilla Raids Again (1955), what U of MN Press ended up releasing was a two-novella volume adapted from the movies. A watershed translation that I enjoyed very much, but it was unfortunate that Kayama’s original stories—the ones presented to Toho’s creative team—were not included. By contrast, The Luminous Fairies and Mothra contains the text from which Shinichi Sekizawa worked when developing his screenplay.

In what might surprise some, more than half of the words in The Luminous Fairies and Mothra comprise not the eponymous novella but a comprehensive afterword by Angles. As we learn, Toho initially contracted award-winning novelist Shin’ichiro Nakamura to write the story (which appeared in Shūkan Asahi with a byline informing readers that Toho was adapting it into a movie). Perhaps due to his having never published science fiction, Nakamura enlisted the help of fellow wordsmiths Takehiko Fukunaga and Yoshie Hotta; The Luminous Fairies and Mothra was then assembled by having Nakamura write the first act, Fukunaga the second, and Hotta the third. Each man was granted ample freedom to inject his own ideas, characters, and style into this tale about four tiny women (not two, as in the movie) who are plundered from their island—and the price civilization pays when their guardian monster awakens to rescue them.

All of this makes for fascinating behind-the-scenes material, though in practice it yields a story of resolutely mixed quality. For the three scribes not only inflate the dramatis personae (sometimes recklessly) as they go; they also diminish or completely discard subplots and character beats introduced by their fellow authors. Nakamura’s first act, for instance, revolves around a linguist named Chujo. Through him we’re provided both exposition and a hero to accompany on a scientific survey to the aforementioned island. Chujo encounters both wonder (forests of grass) and danger (a carnivorous plant), and he undergoes what seems to be the start of an emotional journey. After discovering one of the fairies, he becomes smitten with her beauty and euphonious voice, and Act One ends on a terrific note with Chujo contemplating the little being who’s captured his heart. Nakamura’s prose is admittedly skimpy in spots, though he manages a mildly engaging narrative through imaginative scenarios and by opening a window for personal drama. Perhaps, the reader suspects, Chujo’s affinity for the girl will become his motivation when she and three of her kind are kidnapped by a greedy impresario.

Alas, this character-centric subplot—and everything that might’ve stemmed from it—is reduced to an afterthought once the story switches authors. Act Two, written by Takeyuki Fukunaga, relegates Chujo to the sidelines and shifts attention to a reporter who’s determined to visit the island and interact with the native populace. (This is preceded by an unconvincing setup wherein he spends a few months studying their dialect and somehow, in that span of time, becomes fluent enough to understand a nuance-laden mythological tale rife with cataclysms, massacres, self-destructing gods, pacts, and the formation of the heavens.) Fukunaga’s portion works as an exercise in world-building, but it lacks the human touch hinted at in Nakamura’s opening. Even the villain, a mysterious foreigner named Peter Nelson, comes up short—particularly disappointing in hindsight as one recalls the scene-chewing panache with which Jerry Ito played his screen counterpart.

Most dissatisfying is Yoshie Hotta’s third act, wherein the titular monster assaults Japan. Some of the set pieces are familiar to those who know the movie—e.g., Mothra spinning its cocoon against a Japanese landmark. (Here, it picks not Tokyo Tower but the National Diet Building—seemingly pointing the way to Takao Okawara’s 1992 Godzilla vs. Mothra.) Which would be fine were it not for the pathetic action writing. Jeffrey Angles notes that “the three authors were aware that the studio would […] augment the story with Toho’s particular brand of innovative special effects. For that reason, certain parts of the story, especially the final action scenes, were left quite sketchy, thus giving plenty of room for the filmmakers to work their visual magic.” Rather than revel in the detail with which Mothra razes cities, Hotta whisks through action scenes sometimes in the span of just a few sentences. And in what adds to the novella’s unfocused structure, he adds—far too late in the narrative—another human character: an activist who becomes a prospective wife for Chujo. (Whatever happened to the linguist’s affinity for the fairy remains unresolved.)

At the end of the day, The Luminous Fairies and Mothra feels like a literary sketch to give the Toho staffers something to flesh out. And yet, I encourage interested parties to check out this translation, as the novella holds undeniable historical importance as a stepping stone toward one of Ishiro Honda’s finest genre pictures. I also recommend it for Angles’s afterword and the detailed manner in which he explores not only the circumstances under which Mothra got made but also the history of Japanese collaborative literature—and even how Hugh Lofting’s Doctor Dolittle series might’ve (significantly) influenced the book under discussion.

Additional passages cover political events, colonialism, the lives and careers of the writers, and how all the above influenced the story. Example: as superfluous as that student activist is, how Yoshie Hotta got to her is an interesting read. Angles frames The Luminous Fairies and Mothra partly as a response to protests against the 1960 Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan. Opposition to said treaty, which concerned the lingering presence of American military forces in postwar Japan, culminated in activists surrounding the Diet Building (the structure Mothra cocoons at) and hollering “Yankee, go home!” (their literary counterparts chant, “Nelson, go home!”). Hotta even names his activist Michiko—possibly after Michiko Kanba, a young woman who tragically died at the real-life protests. Thanks to this detailed context, one can reflect on the novella and come away with deeper respect for the authors—at least for their intentions. And let it be said that those interested in the Japanese studio system will enjoy Nakamura’s explanation for why Toho didn’t film a proposed scene of protestors surrounding the Diet Building….

When I interviewed Jeffrey Angles after the release of the Godzilla novellas, the translator remarked that monster movie fans had written University of Minnesota Press requesting “a translation of the novel that was the basis for the 1961 film Mothra. […] Since three authors were involved, the rights situation is a little more complex than usual, but if things work out, I hope to produce a translation of this quirky little novel for all the kaiju fans out there waiting in the world!” Fortunately, the rights situation proved workable and this long-out-of-reach curiosity is now available to readers outside Japan.

Postscript: I read The Luminous Fairies and Mothra three times for this review. On my third reading, it occurred to me that a couple of unused ideas from the novella might’ve been purposely recycled for Takao Okawara’s Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992). Besides the bit about the Diet Building, both the novella and Okawara’s film end with Mothra flying into outer space. (In Honda’s movie, the creature simply returns to the island.) Angles writes that Luminous Fairies wasn’t reprinted in book form until 1994—and that the authors excluded it from collections of their respective works—so I don’t know how accessible it would’ve been prior. But part of me wonders if screenwriter Kazuki Omori located and familiarized himself with the story when writing the ‘92 film.

* In the interview, Honda erroneously recalls that four novelists were commissioned to write the novella and that the story—like the film—featured two fairies instead of four.