Ryo is an underwater photographer who works mainly around Suruga Bay and Kume Island, places where the deep sea meets the open ocean. With more than twenty-five years of experience, he is regarded as one of the leading specialists in photographing planktonic and pelagic marine life, revealing forms and behaviours that are rarely seen or documented.

His work blends scientific insight with artistic sensitivity, and he collaborates closely with researchers across a wide range of fields, including scientists from the Smithsonian Institution, OIST, and universities throughout Japan. Through these partnerships, his photographs have contributed to the understanding and documentation of species that inhabit the ocean’s most elusive and mysterious realms.

Ryo also hosts Blackwater Dive experiences on Kume Island, Okinawa, guiding divers into the offshore night sea where they can encounter pelagic organisms in their natural environment. His images have been featured internationally, including in National Geographic and other global publications, and he has presented his work in exhibitions and books both in Japan and abroad.His photo collections and publications, which explore the hidden beauty of plankton and deep-sea life, continue to inspire both general audiences and scientists around the world.

How did your journey into photography begin, and what drew you to photographing marine life in particular?

My path into photography began with a simple wish to understand the world that lies beneath the surface and to share that unseen world with those who have never encountered it.

I grew up playing in nature from an early age, and before I realised it, I had become deeply drawn to the presence of living creatures and the essence of life itself. When I first held a camera underwater, it felt almost like being given a new language. Suddenly I was able to capture moments of creatures that are fragile, fleeting, and visible for only the briefest periods of time.

What moved me most was the ability to portray the world as seen from their perspective. It is a realm that most people never notice, even though it certainly exists. There is so much to learn from these small lives, and sharing their stories has become, for me, a way to show respect for them.

You work near Suruga Bay, the deepest bay in Japan. How has this environment shaped your eye as a photographer?

Suruga Bay is known as the deepest bay in Japan, reaching depths of more than 2500 meters. The place where I first began diving, Osezaki, lies at the very inner end of this bay. Across the water stands Mount Fuji at 3776 meters, creating a rare and almost luxurious landscape where a deep, plunging sea and Japan’s most iconic mountain exist side by side.

As I continued diving day after day, almost like taking a daily walk into the sea, I began to sense the seasonal changes underwater, the behaviours and rhythms of marine life, and even the individual personalities of fish. I also learned to feel the ocean through more subtle signs, such as long swells arriving from the open sea or the delicate shifts in the currents. Over time, I became sensitive to small changes that I had never noticed before.

I found myself naturally drawn to the quiet details. Larvae drifting through the water column, pelagic creatures rising gently from the deep, and faint signs that appear in the night sea all sharpened my ability to perceive a world that is easily overlooked.

My time in Suruga Bay constantly reminds me that the ocean is filled with countless forms of life, each carrying its own silent story. That awareness still shapes the way I approach photography today.

You mention that the theme of your photography is ‘the preciousness of life’. What emotional or philosophical response do you hope people feel when they look at your images?

The theme of my photography, the preciousness of life, comes directly from what the small creatures of the ocean have taught me. Many of them exist in their visible forms for only brief moments, or can be encountered only under very specific conditions. I have long been drawn to this combination of fragility and quiet strength that defines their existence.

When people look at my images, I hope they feel a gentle sense of wonder. Countless forms of life inhabit the ocean, each with its own story, even though we rarely see them in our everyday lives. By noticing a single moment or gesture, I hope viewers can sense that every life, no matter how small, has meaning and carries its own beauty.

If my photographs can communicate even a little of the value and vulnerability of these lives, and if that leads someone to feel a desire to protect the ocean or learn more about it, then that is the greatest reward I could hope for.

Plankton play foundational roles in marine ecosystems, and feature heavily in your work. What qualities or behaviours of plankton intrigue you most?

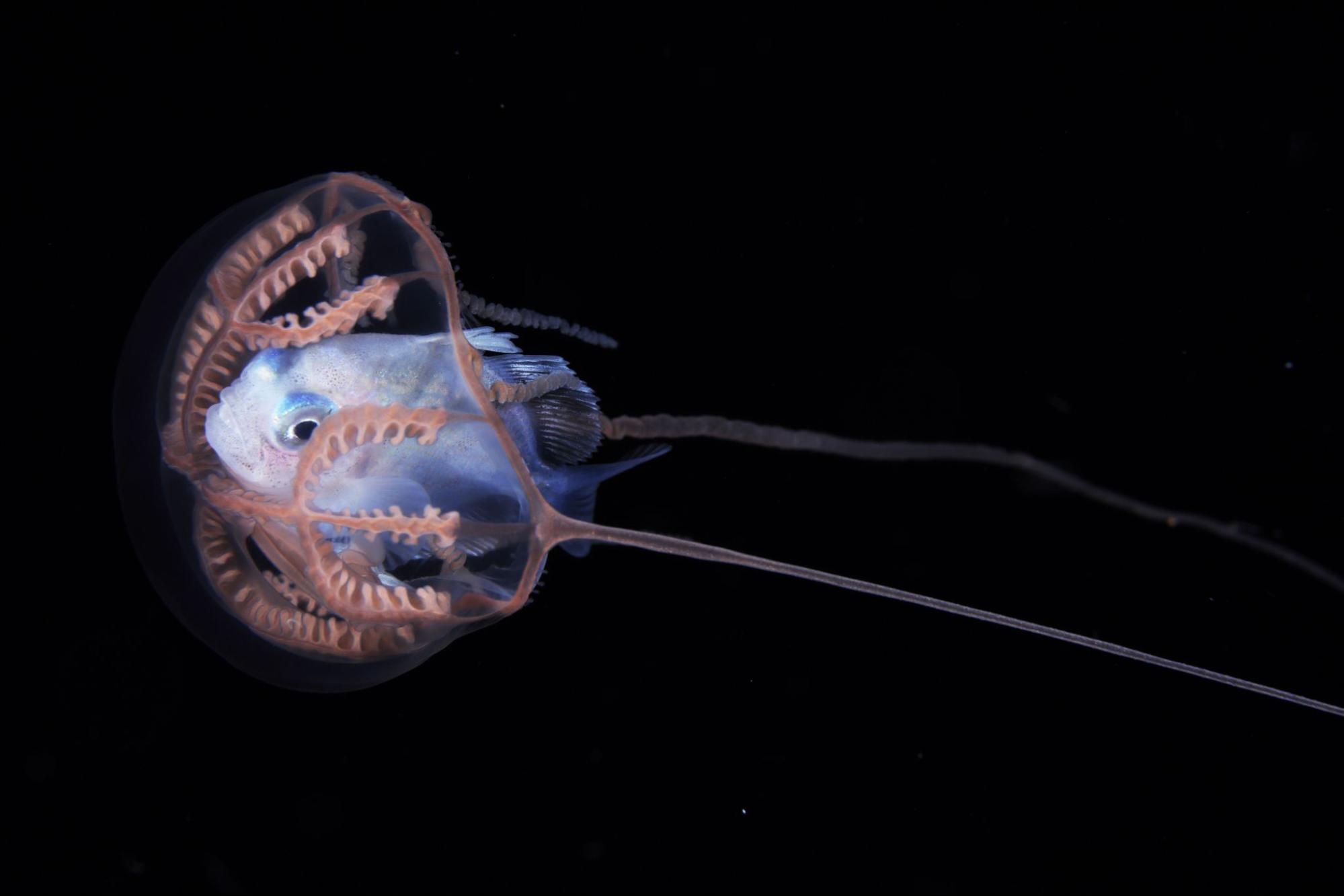

Plankton fascinate me because their forms and behaviours reflect the long history and evolution of the ocean itself. Their shapes can appear surreal or delicate, almost as if they belong to another world, yet every feature is the result of countless years of adaptation. Each movement and structure carries a sense of purpose.

What intrigues me most is the combination of fragility and quiet resilience. Some rely on transparency to avoid predators, some move with thread-like appendages, and others simply drift with the slightest currents. Observing them reveals the remarkable diversity of strategies that life has created in order to survive in the open sea.

Many plankton are also larval stages of fish and invertebrates, and their forms are completely different from the adults they will eventually become. Witnessing these early, temporary shapes gives me a deep appreciation for the journeys that each life must take.

The world of plankton is quiet yet dynamic, and it forms the foundation of the marine ecosystem. Recording their stories has become one of the essential motivations behind my photography.

What do you enjoy most about the experience of blackwater diving?

Blackwater diving in the open ocean feels like entering a world entirely different from the sea we know during the day. After the sun sinks below the horizon, the underwater landscape quickly transforms into deep darkness. The only point of reference is the light attached to the buoy above. As I move slowly through the water, lighting my surroundings with a gentle beam, delicate creatures begin to appear, floating out of the dark.

In those moments I feel that I am truly in the place where they live. Their presence is extraordinary, not only in the way they move or how they look, but simply in the fact that they exist in front of me at that precise moment. When I am with them, I constantly find myself asking how their forms and behaviours support their lives in this vast environment. That search for understanding never ends.

It is a moment when I sense both the fragility of life and the strength required to survive.

The experience brings a quiet, humbling feeling, offering a way of connecting with the sea that is impossible during the day.

Sharing the existence of these creatures, many of which remain completely unknown, with as many people as possible is one of my greatest goals and one of the true joys of my work.

You’ve photographed for scientific communities as well as broader audiences. How does your approach change depending on who the work is for?

My approach to the subject does not change greatly whether I am photographing for scientific communities or for the general public. What I value most is capturing how the organism positions itself in the water and how it relates to its surroundings and to other life. I want these relationships to be clear at a glance.

To achieve this, I must ensure that I do not place any pressure on the subject and that I avoid creating unnecessary water movement when approaching it. Some organisms rest close to other structures or hide among objects, and if I approach too quickly, they may withdraw or disappear entirely. For this reason, I begin by keeping a little distance and observing their reactions. Only after sensing that they are comfortable do I slowly move closer. Because many of these creatures rely on water flow to maintain their posture, any disturbance can cause them to drift or bend unnaturally, which means the scene no longer represents their true form.

With this foundation, there are additional considerations when photographing for scientific documentation. It is essential to understand in advance which morphological features are important for classification. Whether those diagnostic points are clearly recorded greatly affects the value of the image. I make sure that the morphology, colours, and features can be interpreted objectively, paying close attention to lighting angles and colour accuracy. The photograph must hold biological meaning. It also needs to serve as a reliable record.

For a broader audience, I focus more on emotion and storytelling. I choose composition, light, and colour in a way that conveys the beauty, mystery, and atmosphere of the moment. I aim not merely to show the organism but to express the meaning held within that unique moment.

Although the approach shifts depending on the purpose, the intention behind both remains the same. I want to help people understand and appreciate the quiet lives that exist within the sea.

What advice would you give a photographer trying to photograph microscopic marine life for the first time?

When photographing microscopic marine life, the most important thing is to work within the limits of safe diving and to face the subject only within those boundaries. It is essential to respect depth and time limits and never allow yourself to think that “a little more” is acceptable. If safety is compromised, nothing else matters.

Both the photographer and the organism are carried by the water, which means the time you can spend with the subject is often very limited. Depth restrictions may force you to leave sooner than you would like, and drifting too far from the buoy can put you at risk of being carried off alone into the open sea. Maintaining awareness of your position and safety is crucial.

It is also important to observe before approaching. These organisms may appear to follow patterns, yet in reality they are extremely delicate and unpredictable. Begin by keeping some distance and watching carefully how they move, which direction they tend to favour, how they react to light, and how they use the surrounding water to stay afloat.

Approaching requires just as much care. A sudden movement may disturb the water flow, causing the organism to tilt unnaturally or stop moving altogether. If you get too close and then pull back in a hurry, you may even draw the subject towards you and lose sight of it. Try to sense how the organism is reacting to your presence. Keep your distance at first, observe its behaviour, and then move closer very slowly while avoiding unnecessary water disturbance.

Another essential aspect is prior knowledge. Understanding even a little about the biology and behaviour of plankton and larvae, or knowing which features are important for identification, will completely change your approach. With knowledge, it becomes clearer what you should prioritise in the photograph.

Above all, value your own curiosity. If you remember why you were drawn to the creature in the first place, and if you hold on to the sense of wonder you felt when you first encountered it, you will naturally understand what needs to be captured. That feeling will always be reflected in your photographs.

Are there species or moments you still dream of capturing?

It is no exaggeration to say that every encounter feels like a miracle, yet there are still many creatures I dream of photographing someday. The larval Ocean sunfish and the larval Pacific Black dragonfish are only two examples, and the list could go on endlessly.

Larval organisms living in the open ocean exist far from the world humans inhabit, and in many cases, they look completely different from their well-known adult forms. In the brief moment when a life moves towards its next stage, the accumulated history and evolution of the species are revealed, holding a quiet and compelling beauty. Some of these creatures have never been seen by humans at all. I often find myself wondering, “What kind of animal will this tiny being eventually become?” Each encounter reminds me that the ocean still holds vast realms we have yet to understand.

The sea is constantly changing, and no moment ever repeats itself. No matter how much experience I have, I can never predict what will appear next or what form it will take. This is why I return to the ocean night after night, always hoping for a new image to capture. When that rare moment arrives, I want to be ready to record it faithfully, and I hope to continue facing the sea with sincerity for as long as I can.