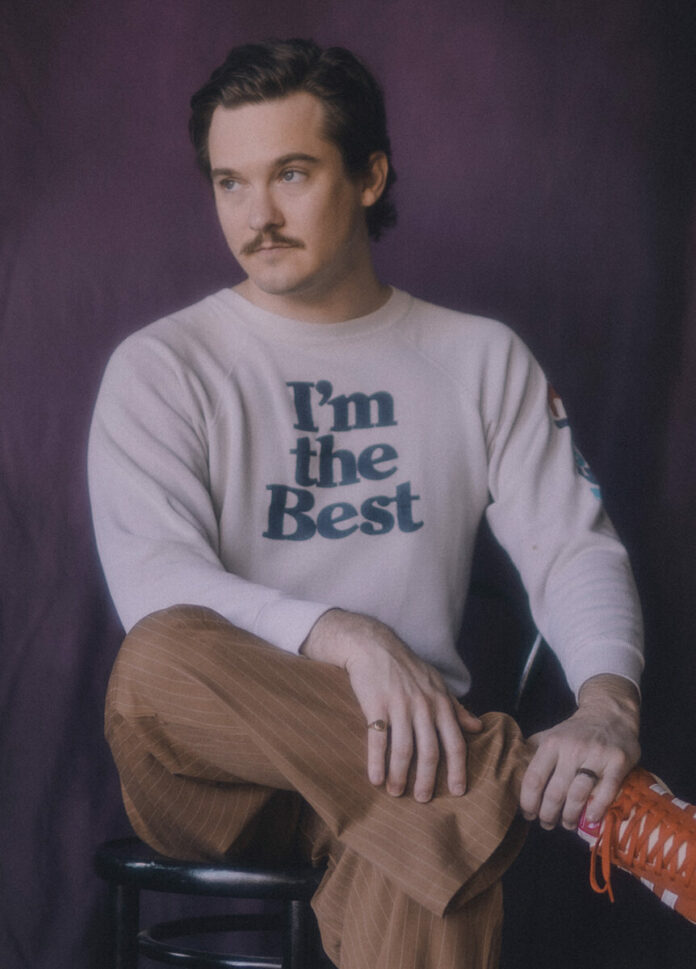

Born in Michigan, raised in Florida, and now based in Los Angeles, Chris Farren made his name fronting the now-defunct punk outfit Fake Problems and recording with Antarctigo Vespucci, his collaborative project with Jeff Rosenstock. For the longest time, his solo career has been a one-man project with a kind of full-band sound, entirely based around but also playfully distanced from his own personality; he made his solo debut with a Christmas LP featuring artists such as Sean Bonnette, Laura Stevenson, and Mae Whitman, while his 2022 record Death Don’t Wait was conceived as a soundtrack for a movie that doesn’t exist. In between, 2016’s Can’t Die and 2019’s Born Hot showcased his knack for melodic power-pop hooks and self-deprecating lyrics, expanding in brightness and sound in ways that come into focus on his latest record, Doom Singer. Farren’s most ambitious and collaborative effort to date, the album was produced by his Poyvinyl labelmate Melina Duterte, aka Jay Som, and co-written with Macseal drummer Frankie Impastato, resulting in a record whose anthemic moments are more dynamic and whose sincerity shines through the bombast and tongue-in-cheek humour. What you hear in Doom Singer isn’t just Farren comfortably revealing more of himself on record, but the freedom of embracing not always knowing what that means.

We caught up with Chris Farren for the latest edition of our Artist Spotlight series to talk about promoting his music, the collaborative nature of Doom Singer, his lyrical process, and more.

What was it like conceptualizing the promotional campaign for Doom Singer compared to your previous albums?

For me, I’ve always seen the promotion of an album as kind of an extension of the artistry of the album itself. That’s the way I’ve been able to make promotion not torture, for me, is to try to figure out how to just make it artistic or funny to me. To make the album, the music videos, the posters, the merch, the marketing feel like it’s one thing, as opposed to: it’s a record, and I have to do all this other stuff so people listen to the record. That obviously evolves, because you can only do so many things so many times before you get sick of them.

You treat the whole process with a lot of self-awareness, and obviously leaned into that with the video for ‘Cosmic Leash’. I hope this isn’t too meta, but what were those early conversations with your drummer, Frankie Impastato, and the director, Clay Tatum, about the video like?

I’ve made a lot of videos with Clay. Clay and I have made at least one video for every record I’ve put out since 2016, so we’re really comfortable with each other. There were two weeks where we were just trying to think of an idea for the video – we had one idea that was, I was going to be in an inflatable latex suit that keep inflating through the duration of the music video and just knocking everything around me down, but it turns out those are very expensive, and they take a long time to make, so we canned that. I had it in my head that maybe we could make a 30-second promo video that would just be me going like, “And I’ve got a new drummer,” and she would come out from under a tarp. That idea turned into the entire music video idea, and it just snowballed from there between Clay and I.

What inspired you about Frankie as a musician and friend once the two of you met, and when did you realize you’d be making this record together?

Her band, Masceal, and me were both opening for a band in 2019, so that’s how we met. When you’re on tour, you kind of just gravitate towards the people that are like you the most, and we just go on really well. During that tour, I was planning my headline tour, and Frankie literally was like, “You should take us on that tour too!” [laughs] I was like, “Alright!” So that happened, and then on my headline tour, Macseal and I rode in a van together and had a great time. When the lockdown started, Frankie and I just started FaceTiming each other every day, just as a way to kind keep each other sane, and our friendship kept growing from there. I made a soundtrack album that I had her play drums on for a few of the songs, and it was really easy and fun to do that. I was like, man, Frankie is like the first person I’ve met that I want to be in the Chris Farren band, that I can see sharing this experience with. So I was like, “Would you wanna maybe make a real record with me, and maybe we could tour on it?” She was very receptive to that, and we started writing songs together, which was really fun. She has such a great creative mind, so it was a no-brainer for me. I’m lucky to have her.

How far into the writing of the record were you when you started collaborating?

I spent maybe three months at home here, every day waking up, writing a song, and then after a period of time, I would get all the songs together and look at them, listen to them and put them in their own little categories of where I thought they landed. I had a folder Tier A, which is what I thought were the best ones, Tier B, which is like, “Maybe these aren’t great, but there’s something there,” or C, where I’m like, “These songs suck, but maybe, Frankie, if you want to listen to them, and if you think anything’s good about them, let me know.” And then tier D, which is like, “These are absolutely terrible songs.”

And you didn’t send them.

I sent them, but I was like, “Don’t you dare even try to tell me any of these are good.” [laughs] So I would make either acoustic demos or just a Garage Band demo, and after I did all of that, I went to New York to get with Frankie in our rehearsal space and just start playing through all of them, trying to figure out what feels good. Frankie would write her own parts, and we would both talk about the songs, rewrite lyrics if they needed to be. Specifically the song ‘Only U’, we rewrote the entire song. It just wasn’t working, and somehow we worked it out. So it would start in a very solitary place, but then we would come together really figure out the structure and the bones of the songs. And then, when we went to the studio with Melina, that’s when we would think more about, like, lead guitar parts or more sonic elements to improve them.

How do you feel sharing the songs with these specific people opened them up? Do you think they saw in them something you maybe hadn’t?

It’s hard to say specifically, but certainly they both brought so much to all of it. Collaborating with people is just so interesting and fun, because everybody has different frames of reference. I can write a song and I think it sounds like a power pop song, but somebody else could be like, “But what if we made this more of a ‘60s girl group sound?” People’s aesthetics leak into everything, which is the most exciting part of collaborating. At the essence of it, everybody’s personalities I think found their way into it, which is nice for me, because I don’t want my music to be too my personality-driven – obviously it’s my voice, and my records are kind of state of the unions of myself every time I make them, so undeniably there’s already an absurd amount of Chris Farren on every Chris Farren record. [laughs] So to have some other perspectives in there to help contextualize things and focus in on parts was very helpful to me.

What are some of your favorite memories from being in the studio?

Melina lives like 10 minutes away from here, so it was nice to have somewhere to go to make the record every day and not just be at home all day. It was so nice to get to work every day in the morning and have lunch with Melina and Frankie, just talk shit and hang out. It was just a really good hang most of the time, and then we would work on our little things and try to figure out what sounded good. I think that just speaks to Melina’s strength as a producer, that she cultivates such a great environment to make music in – that, and that she’s sonically so smart and just makes things sound so good. I can’t recommend Melina highly enough.

I think there’s an unfair expectation we put on artists that they need to sound more confident with every new release, an idea you kind of poke at on the title track. But I wonder if you actually did feel like this was the most confident you’ve felt making an album, in part because of the people you made it with.

Absolutely. I was so much more comfortable and supported by the people around me. I have support in my life all over the place and I have great friends and family, but most of the time when I have made records in the past, I make them in a very tiny room next to this room, and I’m just thinking “Is this good?” the whole time. Just to have somebody to go, “Oh, that’s cool,” when you do this little something, it just helps so much in the process. Just by virtue of having such collaborative, sweet people around me, this certainly was the best I felt making an album. And it’s simply easier to talk about and to promote an album when you’re proud of the work – obviously, the work that I did I feel good about, but I want to showcase my friends and how good of a job they did. It’s a lot easier to talk about that than to talk about me going, “Look! Don’t you think I’m cool and smart for thinking of this idea?” [laughs] It’s like, “Look at the fretless bass line on ‘Statue Song’, Melina did that,” or “Jeff played horns on this, isn’t that so cool?”

That kind of translates – I wonder if it has made me more confident in general, I don’t know yet, but we’ll see. But the more we worked on it together, and the more invested that they were, that was huge in and of itself. I kind of realized: We are actually making this together, they want this to be good just like I want it to be good, and they believe in it. I guess I always believe in myself, but kind of have to remind myself sometimes that I believe in myself. [laughs] Their enthusiasm for working on the album, and their genuine love of the songs we were making, made it all feel a lot more real, and made me feel a certain level of pride in what we were doing and what I had built up to that.

When it comes to lyrics, do you tend to second guess or spend a lot of time tweaking them?

Yeah, and I think in different ways. It’s kind of evolved. I’m always tweaking lyrics, but it used to be that I would tweak them to try to make the songs make more sense – they would always make kind of sense to me, but I would be really concerned about making them understandable to the audience. But now I don’t think like that. I kind of have turned a different corner where I’m like, I don’t want to lock this song into this one lane, where it can only be translated as one thing. I want to make it so you could listen to it and three different people could have three totally different takes on it. That’s not every song, of course, there’s some things that feel pretty straightforward still. But it’s just about my taste and what I’m trying to convey. I think overall, though, mostly I’m just trying to make something that is not embarrassing, so it’s like, “Am I humiliated by these lyrics?” And then once you’re just at least bare minimum not humiliated, then you can start maybe tweaking little things and be like, “Maybe this word flows a little better here.”

I was also thinking of lines like “It was then I realized you would die too,” if you were self-conscious about being vulnerable in that way.

That one specifically I remember because it’s just so real. When I got married, it never occurred to me that my wife would ever die. Obviously it occurred to me, but it just became so much clearer in my mind that, like… life is impermanent, you know. [laughs] I just wanted to write that down, without thinking too hard about it or anything. I feel like I’m still working through what that means in different ways. But it was something that happened to me, and it just felt like something worth exploring in a song. It’s not a sad song – I mean, the song is kind of weird and freaky, but that line to me is not sad. It’s like an expression of pure love for someone; to realize that they’re gonna die, and that you’re sad about that. It seems so simple, but yeah.

You can put down the darkest thoughts about yourself and have it come off almost casual, but expressing that about someone else can suddenly make it feel real and heavy.

Yeah. I’m sure there’s parts of the record that veer away from this, but in general, I try not to be too poetic or anything. I try to make my lyrics feel conversational-ish, or just like something that I would actually say, not a very flowery version of something I would say. Obviously, there are times when I feel a little goofy, but I like the idea of covering vulnerable, big feelings kind of casually.

I read that you were inspired by films like Tár and I’m Thinking of Ending Things, the fact that you’re never sure how to relate to the main characters. But it becomes a different challenge when the character you’re working with is basically yourself, and you have to fit it in the context of a specific song structure.

Like we were talking about, I used to try to give people the roadmap about how to feel about the songs, or make it so the perspective is morally right – try to tie up the message of every song in a bow. And it is almost easier to feel a little untethered from that restriction of making it make sense and having a point that is very concise. It’s not about making stuff universal, either. It’s not like I’m trying to make it appeal to more people. That’s such a bad idea – to try to make stuff that appeals to people, basically. [laughs] It’s more about what is interesting to me and what words can I use that would open this up a little bit more.

‘Statue Song’ is quite unlike anything else on the record. At the same time, it makes a lot of sense as the closer. We talked about the title track, but to me, although it’s sung from a non-human perspective, this is the most vulnerable song on the record.

I completely agree. It was probably one of the last songs I wrote, so maybe my next record will be even better. [laughs] That was the one that gave me confidence in this new direction where I’m maybe not being so specific about my own life, but I am being so specific telling such a specific type of story. I’m still kind of working through what that song is probably even about as it relates to me, because it has to be about something – pretty heavy, I feel like, and I have my suspicions and stuff. I’m really proud of that, because it keeps me thinking, and it keeps me guessing about what that song could actually be about – other than, on its face, a song sung by a hundred 50-foot statue.

And it feels personal, because it’s not like the things it reflects on – mortality, art’s place in society – aren’t addressed elsewhere on the record. But it does feel like it opens up something.

It’s so interesting to think that not writing about myself feels like it is the most revealing thing about myself I’ve put out in a while. But I’m not being like, “I feel like this.” I’m telling a story that is doing a better job of expressing some vulnerable feelings than if I was being straightforward.

What are your suspicions?

There’s definitely something about being afraid of being abandoned. I’m curious about what the tourists and stuff mean in relation to myself. Maybe that has something to do with being a very, very, very, very minor public figure, playing shows and having this connection with people that ultimately is very real, but also, people come through your life and they’re gone. That is a kind of love, but it is not a sustainable love.

Like you sing, “They could never hold me in their arms,” which is almost a small moment, but it takes on a lot of weight.

I guess what I’m talking about there is adoration, which is something that’s come up a lot in our culture with parasocial relationships with people. Again, I’m not that famous of a person, I don’t receive an abundance of adoration, but I do get it in those small, contained situations of playing shows and stuff. It’s just an interesting thing to learn how to navigate. At least in my mind, there is a little bit of separation between me in reality and me as a musician person in the public eye.

The way that song came together was, when we went into the studio with it, the demo was basically just me and the acoustic guitar. I knew I didn’t want it to end up like that, but I didn’t really know what to do. We laid down a very bare bones scratch track above it, and then Melina and Frankie built all the shit around it that was just so cool. And then I had a few things I threw back in there, but they really took it and ran and made it this cool thing. It just becomes so much more fun for me, because I can listen to this and not just feel like, “Oh, I did a good job making this.” I can listen to it and be like, “Oh wow, they did such a cool thing with this song.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Chris Farren’s Doom Singer is out now via Polyvinyl.