Let’s talk about complete games.

I still remember the first gaming system I ever bought. A Sega Master System 2 which my brother and I purchased together, alongside Tom and Jerry: The Movie (the game). This, alongside the inbuilt Alex Kidd in Miracle World, would be our first forays into complete gaming experiences. Formerly only having played with a comparatively limited Atari 2600, this new console was nothing sort of a revelation. Of course, by today’s standards, these games and systems are hilariously limited. Two button controls, incredibly low resolution and a story which could be completed in around half an hour meant a sort of hard limit on how long they could hold our interests, but for impressionable young minds, this was far longer than it should have been.

In many ways, we see video games today as a simple evolution of the rules set out by the first console generations. Games would get bigger, graphics would improve, and gameplay would become increasingly in-depth and complex, and yet not all of these developments are welcome or positive. As you might have guessed from the title, there is one area where the modern game often cannot, or does not even try, to match the cohesion of the products of so many generations ago. This is, in basic terms, the idea of a complete game.

Buy the base game (and maybe the expansion), get the complete package. This is how it was meant to be, this is how it will be experienced, and that is that. Well, not anymore. Today, what we think of as a complete package is no longer a matter of a single simple product, but rather a line of related products, expansions, DLCs, and add-ons which, only when combined, form the sort of cohesive whole that we used to be able to find a simple single cartridge. How did we get here, what are the most egregious examples of this, why is it done, and is it as bad a development as my entry paragraphs seem to be indicating?

Ye Olden Days

The early days of a full game being stuck on a single cartridge, disk, or set of disks, was as much a reflection of the technology of the time as anything else. Teams were much smaller, the maximum data limit was hilariously limited, and consoles simply could not accept more than one game at a time, and had no long-term memory. In other words, even if companies wished to release add-ons, upgrades, or expansions in early days of Nintendo and Sega, they usually couldn’t. What was shipped was the final product, and while there were a few attempts to circumvent these limitations, as with the Sonic and Knuckles lock-on pack for the MegaDrive/Genesis, these were unwieldy and difficult to build.

Short of taking a big risk, and spending a lot of money, this was how the game was played. This certainly meant that there would be occasions of limitations of scope, as games still had periods of crunch where later patching was not feasible, and so almost finished elements would often end up cut completely. Fewer buggy additions are great, but a few initially buggy features which might be patched eventually could bring a lot of fun to a game. This ties into the idea of what pundits like Jim Sterling have dubbed early AAAccess, but that is an article for another day.

Expansions Expanding

PC gaming was a fundamentally different beast from the early console market. In terms of use in video games, a large portion of this came down to the inclusion of hard-drives and their enormous storage capacity. Cartridges had barely any storage, with the SNES and Mega Drive/Genesis generally maxing out at around 4MB. While this particular part of the problem was largely solved with the adoption of the CD as game storage, boasting a massive 700MB, the consoles which operated with these CDs still had severe limits on their own writable memory capacity. In fact, early systems like the PS1 relied on memory cards, which were only really used to store save data.

PCs, on the other hand, both allowed high capacity read-only memory and high capacity storage. This meant that the potential for game expansions on PCs came about far before their console counterparts, and appeared far more commonly. Over time, as consoles continued to evolve, bringing with them their own mandatory hard drives from the 7th generation onwards, and with this bridging, crossing this gap became increasingly simple. The other change, the one which gave the industry the ability to focus on expansion development more than ever before, came from the proliferation of the high-speed internet.

Enter Horse Armour, Open Floodgates

The exact term of expansion, in a gaming context, used to strictly refer to large portions of software which brought significant extra gameplay to an already released game. A new land in The Elder Scrolls, a new act in Diablo 2, or a new story campaign in Half-Life, whether standalone or requiring the base game. From a business perspective, this made a lot of sense.

In the early days of the internet, data transfer was extremely limited. Releasing a new product over the internet meant that not many would be able to download it, thus limiting potential sales. On the other hand, releasing a full-sized expansion in retailers or through mail-order is an enormous and costly undertaking, so if the release didn’t have enough depth then a lack of sales would render the release as a fiscal loss. As the internet kept getting faster, and more people kept finding access, this problem would lessen, until the point where full online distribution was no longer anywhere near as cost-prohibitive.

It was inevitable, given this situation, that there would arise those to take advantage of a new market so rife with opportunity, and while it was not the first to test and taint the water, it was Bethesda Game Studios who gave us the best indication of what was to come. This came in the form of the now famous Horse Armour, released on April 3rd of 2006. A small paid download (what would later become known as a microtransaction), which offered an almost useless cosmetic piece for an entirely single-player experience. This armour was cheap, costing only $2.50 US, yet was widely decried and met with significant backlash from gamers.

The problem which so many of us had was not just with the item itself, but with what the item represented. It used to be that such cosmetic enhancements would be locked behind gameplay achievements, or cheats, but Bethesda had opened the world to something else. That which used to be for free could now be monetized, that which used to come with a game could be stripped and sold back, and the overall experience could be crippled in an attempt to play the market. Of course, there were those ardent defenders who saw this type of slippery slope argument as unnecessary and ridiculous, claiming that developers would never do such a thing, but in time even those most dedicated would struggle to defend was is increasingly seen as an ever-expanding rot.

The Best of the Worst

Downloadable Content, or DLC, became the given term for this type of transaction. It was a perfect fit – content says nothing of the range or worth, and comes without the legacy or expectations which people think of when something is called an expansion. The potential had been unleashed, and the industry was getting ready to flex its legs and see just how far this envelope might be pushed. Many of these avenues were just as had been predicted, and were just as insidious.

For a start, let’s begin with the problem of on-disk DLC. This is content which was completed before the game was released, placed on the actual game disk, shipped with the game, and then sold to the customer at an additional cost to the base package. Capcom was one of the first to jump on board this method, with 2012’s Street Fighter X Tekken containing a whopping 12 characters already within the game files, yet locked away. Naturally, fans were not especially happy with this development, and the lackluster corporate PR excuse of an explanation did little to assuage anger at the company for this practice. While the industry now anticipates the type of file mining which makes these types of discoveries possible, indications are that this has simply evolved into day-one DLC, the content available for download immediately after release which still only comes at an often significant additional cost.

Dragon Age: Origins was a game which had a lot of people excited before it launched. A modern RPG somewhere analogous to a more action based Baldurs Gate, which included an all-new world filled with character and lore. As your character take a little rest not far into the game, feeling the deep level of engagement only possible through such a personally and artistically crafted world, you wonder what this little camp has in store next. Then you run into an NPC which tells you that this quest is only available with the purchase of DLC, shattering the fourth wall in an incredible display of tone deafness. A major and unavoidable part of the main game taunts you with the realities of your incomplete experience. Did you buy an entire product? I think not! Spend more!

Then we have the joy of pay-to-win or boost microtransactions. Unlike the other types of DLC mentioned, these type of payments don’t necessarily unlock game content which would otherwise be hidden away, but rather they give a massive advantage to certain players which utterly ruins any concept of an equal playing field. Playing a multiplayer game and getting your butt kicked? Spend extra money, pay for a literal stronger gun or boost, to level faster and skip the grinding which those suckers who bought the base game must suffer through. Literally pay to win. While this sort of action has been gaining momentum for a while now, the recent backlash to how EA included pay to win with Battlefront 2 might have put a damper on what these companies feel they can get away with, at least until they feel public attention has shifted enough for another attempt.

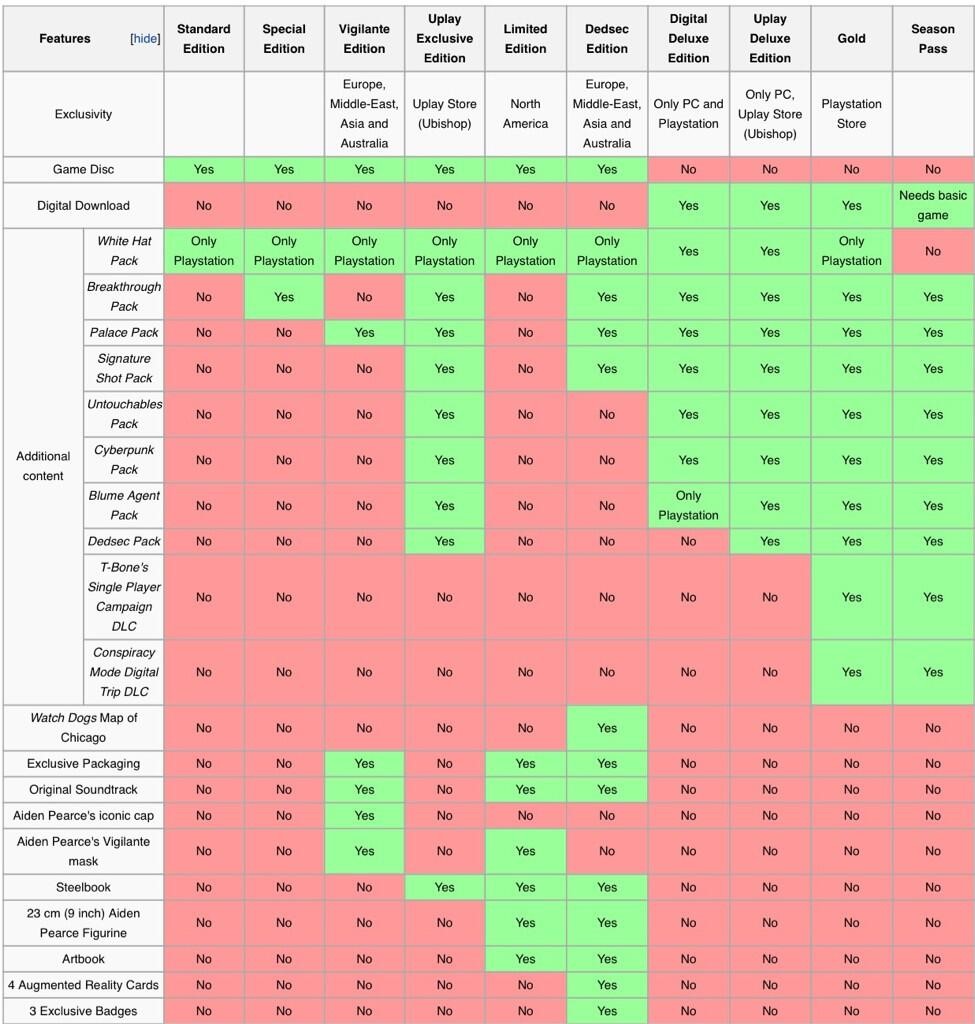

In basic terms, the complete version of a traditional video game would tend to come in two parts – the base game and the expansion. Two parts of a whole, simple and clean. Now, let’s take a look at a spreadsheet which illustrates how the player would manage to get the full experience out of a full game such as Watch Dogs.

Even when we exclude the special edition box features, what we are left with is a rather complicated picture which is distinctly unhelpful to the average consumer unsure of how to get the best experience.

Altogether these paint a picture of baseline experience which is simply not a complete package. There can be already completed gameplay elements already on the disk which you need to pay to access, you will be brought out of your experience by increasingly cloying and unavoidable attempts to sell you more, and you can very well be beaten by those whose only advantage was generated through their willingness to shell out on top of an already supposedly complete product. This is the reality of modern AAA gaming, and this is a pattern far too profitable to be going anywhere.

So, what can you do? The best answer is to vote with your wallet. Don’t support the companies which would engage in these practices, and send them the only type of message that they understand. We can’t promise it will actually make a difference, but at the very least it means we won’t contribute to the further disrespect of as consumers and video game fans both.