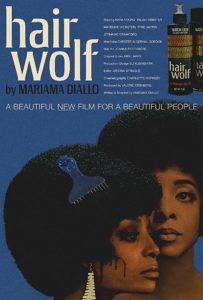

Mariama Diallo’s Hair Wolf is nothing short of an ode: to the Black salon, spiritual religions, to Brooklyn, the ‘70s blaxploitation aesthetic—but mostly, to Black women.

Tackling overarching themes concerned with the impact of gentrification and appropriation on Black folks’ actual lived experience, Hair Wolf operates through the horror-comedy camp native to the exploitation films it riffs on. Clocking in at twelve minutes, this short is both hysterical and subversive while notedly refraining from any exploitative treatment of its subject matter. Which is all to say, it operates squarely within the broader tradition of Black Horror, which casts aside the projection of the White Male Gaze to reconstruct our concept of the monstrous.

Diallo’s landscape of choice for this exploration is the contentious subject of hair. The film is obsessed with it; reflecting many of the ways American white supremacy is similarly obsessed with regulating and surveilling Black folks’- and more specifically, Black women’s- hair. Latent in this hypervisibility is a simultaneous fetishizing and devaluation, wherein our hair, our bodies, our fashion, and cultural traditions are deemed undesirable unless featured on a white body. There is no better example of this than the Kardashian Klan.

It must be noted that the women of Hair Wolf are fly as fuck, and the short’s overall costume design and cinematography make it an absolute aesthetic delight, while still remaining true to itself as a monster movie. This is not a film whose stylization should be ignored, but rather contributes in a major way toward establishing its subtext.

In her 1980 text, Powers of Horror, French feminist theorist, Julia Kristeva, defined the abject– the horrific- as that which crosses a perceived border. Thirteen years later, Australian cultural critic, Barbara Creed uses this concept to explore the ways the feminine has been coded abject in her book, The Monstrous Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis:

The horror film attempts to bring about a confrontation with the abject (the corpse, bodily wastes, the monstrous-feminine) in order to finally eject the abject and redraw the boundaries between the human and non-human (Creed 14).

Together, these texts have helped establish the ways that nearly the entire tradition of horror is rooted in this anxiety of trespass: of the psyche, the body, the dwelling, the nation-state, the planet itself.

Hair Wolf makes new use of the monstrous feminine, redrawing the borders of the abject to also situate itself within what we may consider ‘gentrification horror’ (Candyman, The People Under the Stairs)—part of a larger tradition of films whose horrific elements hinge on the trespasses of our lives’ literal infrastructure: cities (28 Days Later), malls (Dawn of the Dead), suburbs (It Follows), and haunted houses (Poltergeist).

In this case, Diallo explores the vampiric nature of white exploitation in and of Black neighborhoods, Black culture, and Black bodies. While the film isn’t explicit in its setting, Diallo has discussed it in the context of Brooklyn’s Crown Heights, though it could just as easily take place in Fort Greene, Bushwick, or Bed-Stuy—or any historically Black neighborhood which becomes infested with white zombie trendsters “literally biting people’s style.”

Though Whiteness is often prescribed to the Subject (Inside) position, wherein the white protagonists fear contamination by some threat coded Other, Diallo subverts this formula to reassign feelings of safety and authenticity to Blackness and Black spaces—notedly the salon, the community landmark site of Black intimacy and care.

Hair Wolf is a film made for a Black audience, and references to ritual hoodoo practices function as a powerful through-line in speaking to our specific cultural anxieties, which are both informed by and exacerbated when subject to white infiltration and appropriation.

This tension is foreshadowed in our initial introduction to characters, Janice (Trae Harris), Eve (Taliah Webster), and Damon (Jermaine Crawford) who are all at the shop after close. As Eve, midway through braiding Damon’s hair, assures Janice, “You won’t catch this man’s hair lyin’ around all willy-nilly waiting for the next bitch to cast some type of jinx.” Shortly thereafter, our lead, Cami (played by Kara Young) bursts through the door, exclaiming, “Guys. There’s something fucking strange in the neighborhood.”

She relays her terrifying encounter with Count Beckula (Madeline Weinstein)– a pallid, dark-haired waif lurking in an aisle at the hair supply shop who asks if Blue Magic will lay her edges (Janice: “girl, what edges?”) before accosting Cami for a handful of hair. Of her escape, Cami proclaims, “You know I had to get her in the eyes with some Afro Sheen,” but not before Count Beckula made off with “a whole chunk of it.” It being her hair.

There’s a rap on the locked door and despite Cami’s protests, Janice opens it to reveal Count Beckula, nasally drawling a single-syllable request for “braaaaaaids.” Claiming to “get these reparations,” Janice invites Beckula inside, a moment significant for further situating the white girl-monster within the vampire canon.

One of Hair Wolf’s most brilliant movements is this play between “brains” and “braids,” which Diallo has stated originally birthed the film’s overall concept. Needing little more than a few white extras in bantu knots to periodically splay themselves on the salon windows, moaning, “braaaaids,” she establishes a parallel between the compulsive drive of consumers to remain ‘on trend’ and the mindless consumption of the capitalist zombie as represented in American cinema through the mid-late twentieth century—itself an appropriation of the zombie born of Haitian folklore.

That’s all happening outside though. Inside, lurks Count Beckula.

Vampires of & for fashion are not necessarily new to horror (Neon Demon, The Hunger), but in this context, vampirism is established through the act of appropriation, wherein the Count Beckulas of the world suck the lifeblood out of Black culture, yes, but more specifically, Black women’s selfhood.

When asked what style she’s looking for, Beckula replies, “Something funky. You know, like Rihanna.” She lets out a scream which startles the other characters, but then releases the tension with a chuckle: “I thought it was a little bug but it’s just your hair,” before posing with the tuft as a Hitler mustache. Her camera flashes, capturing Janice’s look of incredulity in the background. “That’s gonna go viral.”

It’s not just that Count Beckula is a vampire of culture—she’s a contagion. Her monstrosity is constructed on compulsive consumption and entitlement, engendering the commodification of the Black woman’s body with her overlined lips and chicken-cutlet ass enhancers; what Damon refers to as “Oakland booty.” Her reduction of our bodies to spare parts- bits to pick and choose for consumption- echoes the violence of our literal commodification under slavery and the endurance of this psychology over time.

Beckula is the contagion but the virus is internalized anti-Blackness.

When Janice returns from a back room, her gorgeous mane of black and purple kinky curls have been replaced with stick-straight, platinum blonde strands she continuously runs her fingers through; a decision which was extremely evocative for me on a personal note, as it recalled the ghost of my little girl self who so desperately longed for the ability to make that combing gesture, which my hair would never allow—that is, without an iron or chemical treatment.

Shocked at her change in appearance, Cami almost whispers, “Janice, why you out here looking like ‘My Little Pony’ girl. What happened to ‘nappy is happy’?”

Janice turns on her. “Nappy? Honey you don’t know my curl pattern. I’m a 3B.”

Gradually, the virus of internalized anti-Blackness spreads. When Beckula “goes viral” on Damon, Eve’s despair at his leaving her to walk out with “a whole pig” exhibits the very real pain of desirability politics and colorism, which denies darker-skinned Black women’s beauty and worth as love interests and romantic partners, particularly within a hetero(normative) context. “…you could have the most Black like, Black Power, Black Lives motherfucker- and he still be waiting for his shit to be with some white girl.”

The virus of self-loathing threatens to claim Eve (“People out here talking about ‘black girl magic’ like we living in Harry Potter”), and just like Janice and Damon, the shift is embodied through her hair. Where she previously had it done in a beautiful Nigerian textile headwrap (what one might imagine is a direct reference to the history of the Tignon Laws and their influence on Black women’s fashion), she suddenly emerges, distraught, in a short, blonde bob. The following exchange between her and Cami is both completely earnest and completely terrifying for the accuracy of its mirroring the specific pains of Black women’s lived experience.

“Fucking white girl went viral on your ass,” Cami observes. “Fight it. Love yourself. Black power is real.”

With Cami’s support (and a slew of reminders about the undeniable truth of Black beauty), Eve is able to defeat the internalized anti-Blackness inspired by the virus. “You just gave me life,” she says as the two embrace.

Hair Wolf acknowledges the trauma we experience raised as Black femmes and girls and women in a white supremacist capitalist patriarchal world—but it does not exploit it. In the tradition of Black feminism, it offers a way forward through self-love and sisterhood without underestimating the monsters of white supremacy and internalized self-hate that we’re up against.

This film is nothing short of a poem. Diallo seamlessly weaves and breathes new life into the monsters of contagion- the vampire, the zombie, the virus- to showcase the existential threat of whiteness trespassing on the banalities of Black life.