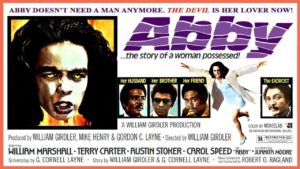

For fans of blaxploitation horror, 1974’s Abby is perhaps most notorious for its marketing as “The Black Exorcist” (nearly named ‘The Blaxorcist’) and having achieved the honor of being sued into (literal) oblivion by Warner Bros. for copyright infringement. It’s undeniably true that the script is, shall we say, lacking in original thought — part and parcel for a blaxploitation feature, right? After all, low budget, big profit is widely understood as the definitive model of exploitation moviemaking in the first place.

But there’s also that slightly more elusive quality all horror fans recognize in exploitation films — the illicitness. It’s so bad it’s good circled back around to bad again. Watched through eyes distanced by nearly half a century, we understand them as problematic, but love to laugh at the spectacle anyway.

In Horror Noire: Uncut, the podcast follow-up to the acclaimed documentary, co-writer & producer, Ashlee Blackwell, draws attention to how the poor production values – now aesthetically elemental to the genre – reflect a type of cultural mining endemic to the entertainment industry (and American capitalism) in its entirety. A known-but-beloved problematic, we refer to the ‘exploitation’ element in terms of both their content and creation, but what of the wider implications of the business model as a whole?

Abby was written and directed by a white man, William Girdler, a sweetheart of notorious exploitation studio, AIP (American International Pictures), under producer, Sam Arkoff. The film only screened for a month in 1974 before being pulled from distribution, but it grossed $4 million on a reported $100,000 budget.

Adjusted for inflation, this would come to just over $21 million on a $525k investment in 2020. Which is to say, profit puts it demurely — throws a handkerchief over something exceedingly dirty.

Indeed, Carol Speed (who plays the titular character) is quoted speculating that Arkoff didn’t even fight the Warner Bros. lawsuit “because he had already made a ton of money off of Abby.”

As Ashlee Blackwell recognizes, itty bitty budgets meant predominantly young (white) writers with flat, cranked-out, uncaring scripts, populated by characters representing evolutions of slavery-era stereotypes which would continue to propagate a perception of us as social monstrosities (in the form of criminals, etc.). It meant Black talent working on an otherwise completely white set, and gross pay disparity, itself always both gendered and racialized.

While Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman identifies this film amongst other examples of 1970s-produced ‘Black horror’ like Blacula (1972) or Ganja & Hess (1973) in her book, Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films 1890s to Present, I strongly disagree with this estimation — rather, I consider it a key example of her very distinction between Black Horror as a cinematic tradition and Blacks in horror, wherein we’re merely “represented” (often represented poorly) in an otherwise white production.

*

Since very little critical analysis of the film exists (and even less that goes beyond mere recognition of its exploitative and derivative qualities), it’s worth examining Abby in close proximity to the impact of The Exorcist (1973), not necessarily for the ways in which they are the same, but for the places they diverge.

Australian professor and cultural critic, Barbara Creed, writes on “Woman as Possessed Monster” in The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis wherein she defines the monster as that which ‘takes us to the limits of what is permissible, thinkable, and then draws us back.’ She understands the film as establishing a ‘graphic association of the monstrous with the feminine body.’ Thus, the possession functions as an ‘excuse for legitimizing a display of aberrant feminine behavior which is depicted as depraved, monstrous, abject—and perversely appealing.’

Citing French feminist theorist, Julia Kristeva’s writings on abjection and its Biblical evolutions, Creed notes how, in the transition to the New Testament (i.e. the schism between Judaism and Christ-religions), ‘sin is associated with the spoken word,’ and so ‘rather than encourage the possibility of speaking the abject, of transcending sin by articulating it, the Church adopted a brutal policy…toward those who advocated such a path.’ This acknowledgement leads to her conclusion regarding ‘the project of films such as The Exorcist’ which are rendered subversive precisely for their ‘speaking [of] the abject’:

‘Horror emerges from the fact that woman has broken with her proper feminine role – she has ‘made a spectacle of herself’- put her unsocialized body on display. And to make matters worse, she has done all this before the shocked eyes of two male clerics.’

Creed also draws our attention to the fact that Pazuzu is voiced by a woman, Mercedes McCambridge. Bearing her psychoanalytic framework in mind (a framework itself obsessed with incest and genitalia), she cites writers and critics of the time who engage only with Pazuzu as ‘the voice of a male devil as spoken by a young girl’, inconsiderate of an interpretation of Pazuzu as ‘a female devil,’ noting how within patriarchy, her possession by a masculine spirit – even (or especially) if evil – is congruous with social expectation. In considering the option that the character’s casting determines their gender (which would render Pazuzu feminine), Regan’s ‘desire to remain locked in a close dyadic relationship with the mother’ becomes both the source and reason for her possession, affirming a femme & queerphobia which seeks to establish alignments between queerness, pedophilia, incest, child abuse, and the demonic while simultaneously ignoring the potential for trans readings of the film.

Regan is a white girlchild and so the overture of her innocence is already encoded on her body. The horror, as Creed notes, is writ on its corruption: the steadily decomposing state, the blasphemy of a child screaming ‘fuck me’ to her mother while mutilating herself with a crucifix, her refusal to maintain ‘the clean and proper body’ prescribed by what Lacanian psychoanalysis refers to as the symbolic order — what is essentially just white supremacist colonial patriarchal ideology, which collapses the figureheads of the husband, father, church, state, and god, all of whom hold dominion over the Other (another term for Manifest Destiny).

*

It’s necessary to note a related but different form of exploitation exhibited in Abby, whose spiritual and religious tensions are both compelling and numerous.

In order to render the story of The Exorcist “Black”, the choice was made to substitute Pazuzu with who is referred to as Eshu, portrayed as a type of chaotic African sex demon unleashed by archaeologist, professor, and pastor, Dr. Garrett Williams (played by Blacula himself, William Marshall).

I want to be clear that while they may share the same name, this appropriation accounts for an egregious misrepresentation of the Yoruba orisha — a perspective Dr. Coleman explicitly does not share.

In her studies of 1930s horror, she highlights the demonizing of African spiritual religions within American cinema; a tradition ‘almost as long as the medium itself.’ She discusses its appearance and effect in films like Voodoo Fires (1913), White Zombie (1932), Black Moon (1934), and The Love Wanga (1936). By the time of her arrival at Abby, produced some forty years later, she considers the film’s ‘educational commentary’ regarding Eshu, as well as the ‘Yoruba-informed exorcism’ which eventually liberates the titular character, indicative of a shift in attitudes from earlier films which ‘cast the religion as singularly odd, ahistorical, and evil.’

Said ‘educational commentary,’ however, accounts for a reductive, Western-influenced estimation of Eshu which enacts a literal demonization of that which exists outside the purview of Eurocentric & Christ-religion-informed modes of belief. As such, Eshu’s actual complexity is thus flattened within the projection of the colonizing gaze.

*

In Horror Noire (the documentary), Tananarive Due calls Abby “…a really good example of both fear of Black women in general but fear of Black women’s sexuality in particular.”

In order to encode innocence on Abby, a Black adult woman, she had to be rendered the model of respectable Black Christian femininity. At the film’s start, she’s a preacher’s wife and marriage counselor involved with the church, surrounded by “successful” men, beloved by the community. Once possessed, she becomes increasingly lascivious, hypersexual, and violent, just as in The Exorcist. But she doesn’t undergo the physical transformation Regan does. Abby’s monstrosity is indicated largely in language and voice, but instead of rotting her physical form (which would problematize desirability), her monstrousness is prescribed to her overt and predatory sexuality.

There’s a reading in which we might interpret a type of liberation in the character’s acting outside prescribed gender norms, but the shoddy treatment doesn’t create space to navigate this in a way which honors Black women’s relationship to gender as distinct from white women’s. For her possession, Abby has no agency to speak of. The moments when she bursts through the demon’s hold, she is both desperate and terrified. In this way, the film affirms the already-existent notions of Black women’s bodies and sexualities as what theorist, Saidiya Hartman refers to as degraded matter, or what Hortense Spillers has referred to as “flesh.”

Hartman’s essay, Venus In Two Acts, contends with the ways the captive Black woman’s voice is disappeared within the archives of the historical record, accomplished first by disappearing her subjecthood within the projection and prescription of whiteness’ gaze. In this way, she argues, the Black Venus speaks only from negative space, noting how, historically, our bodies have been rendered flesh-spectacle for others’ amusements, pleasure, desire, and comfort — but explicitly never our own.

*

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s Monster Culture (Seven Theses) makes a point of identifying the monster as that which Polices the Borders of the Possible.

He recognizes the monster as a carceral figure, wherein ‘curiosity is more often punished than rewarded…one is better off safely contained within one’s own domestic sphere than abroad, away from the watchful eyes of the state.’ This interpretation of the monster as policing borders of possibility necessarily identifies the parallels between white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism/colonialism, and state sovereignty as interlocking (interbreeding) systems. He writes, ‘the monster prevents mobility (intellectual, geographic, or sexual), delimiting the social spaces through which private bodies may move. To step outside this official geography is to risk attack by some monstrous border patrol or (worse) to become monstrous oneself.’

In her reading of The Exorcist, Barbara Creed’s psychoanalytic framework suggests Regan’s susceptibility to possession as the result of living in a fatherless household with a mother who herself rejects elements of prescribed propriety; the conclusion being, women whose lives are absent men or masculine figures become monstrous as a result (aka daddy issues).

To contrast, no concrete motive for Abby’s possession is offered, though it’s suggested it comes about as a result of her connection to William Marshall’s character, who frees the spirit at the film’s start while on a research trip in Nigeria. As previously noted, Abby’s characterization is distinct from Regan in that she is surrounded by respectable masculine figures – Dr. Williams, but also her husband (a preacher), and her brother, the requisite cop – and it is them who her possession and resultant behavior seemingly seeks to punish. Her monstrosity polices a border of protected and respectable femininity — but it also polices a border of national, cultural, and religious identity, threatening the possibility of what may be unleashed when Black folks go searching for their roots.

All the while, these struggles play out on Abby’s body whose degradation is rendered acceptable for its existence outside both whiteness and cisgender maleness. The prescription of her monstrosity represents, in a word, an ungendering (as coined by Hortense Spillers).

Dr. Robin Coleman’s reading speaks to this point, which – like Creed’s of The Exorcist – concerns itself with the gender of the possessing demon. Voiced by actor, Bob Holt, she notes the queering inherent when the ‘male spirit seeks sexual conquests while in a female’s body’ and points directly to a scene where Abby/Eshu picks up a man and – entangled in the backseat of a car – growls, ‘“You wanna fuck Abby, don’t you?” The demon has sex with his (male) victims, and at the height of the act he kills.’

Of this scene and others like it, Dr. Coleman describes Abby’s ‘oozing sexuality’; notes the ease with which she can be seen ‘seducing her prey.’ But during the act, her voice is masculinized, her behavior frenzied. The camera cuts between her face and the demon to signify their shared state of being.

If we understand the demon as Cohen’s ‘border patrol’ – the fear of which is meant to keep us contained within the carceral systems of race, gender, sexuality, ability, faith, etc. – Abby, the character, moves entirely outside the ‘official geography’ prescribed by her gender into a state of possession (i.e. enslavement) which, again, essentially reinforces the notion of Black women’s bodies as degraded matter.

*

In Abby, unfettered Black feminine sexuality is explicitly made monstrous, but certainly not genuinely scary. For its qualities as an exploitation film, the horror reads more so as camp and is thus rendered humorously. It fails to recognize the history echoing all around wherein our bodies were legally and explicitly not our own possessions. Even in the film’s resolution, following its’ dancefloor exorcism, the inherent “goodness” prescribed to colonial religions (Christianity & Catholicism, with which Yoruba traditions syncretized) serves to perpetuate the notion of our own cultural and spiritual traditions as devilish or evil.

Beyond the act of cultural mining and its ghoulish anti-Blackness, the prescription of evil cast by the colonizing gaze further subsumes our traditions of horror, disappearing them within their projection like so much junk food. This capacity to determine what is horrific within our gaze as opposed to whiteness’ is an aspect of cultural identity lost in endless adaptation and derivation.

Of the film’s conclusion, Dr. Coleman notes, Abby is ‘saved…by her father-in-law, husband, and police officer brother while being restored to favor with her male (Western) God.’ The film forces us to examine the ways in which “the battle between good and evil” is a well-worn weapon of white supremacy whose impact continues to linger in innocuous ways. Ultimately, it begs us to recognize the subjectivity of what we consider evil in the first place.