What can be said about The Giant Claw (1957) that hasn’t been said before? Well, quite a lot, actually. For a film that boasts a bird “as big as a battleship”, it’s something of a shame that the minimal critical attention it’s received has been backhanded at best and derisive at worst.

But let’s get things straight before we begin. The Giant Claw isn’t one of the best of its decade. I don’t plan on arguing that it’s an overlooked gem; rather, it’s simply fine! It’s a decent monster-on-the-loose picture that’s somewhat undeservingly borne the brunt of scorn. Indeed, Alan Jones, reviewing the film for the RadioTimes, called it “one of the most inept monster movies ever made”, and said that it featured “atrocious special effects.”

Little attention gets beyond its giant bird marionette, and discussion is often stifled by myriad inaccuracies that go uncorrected. In part, this arguably comes down to generalisations placed upon 1950s science fiction. In describing all these films as “cheap B-movie fluff”, the incentive isn’t there to report with robust scrutiny.

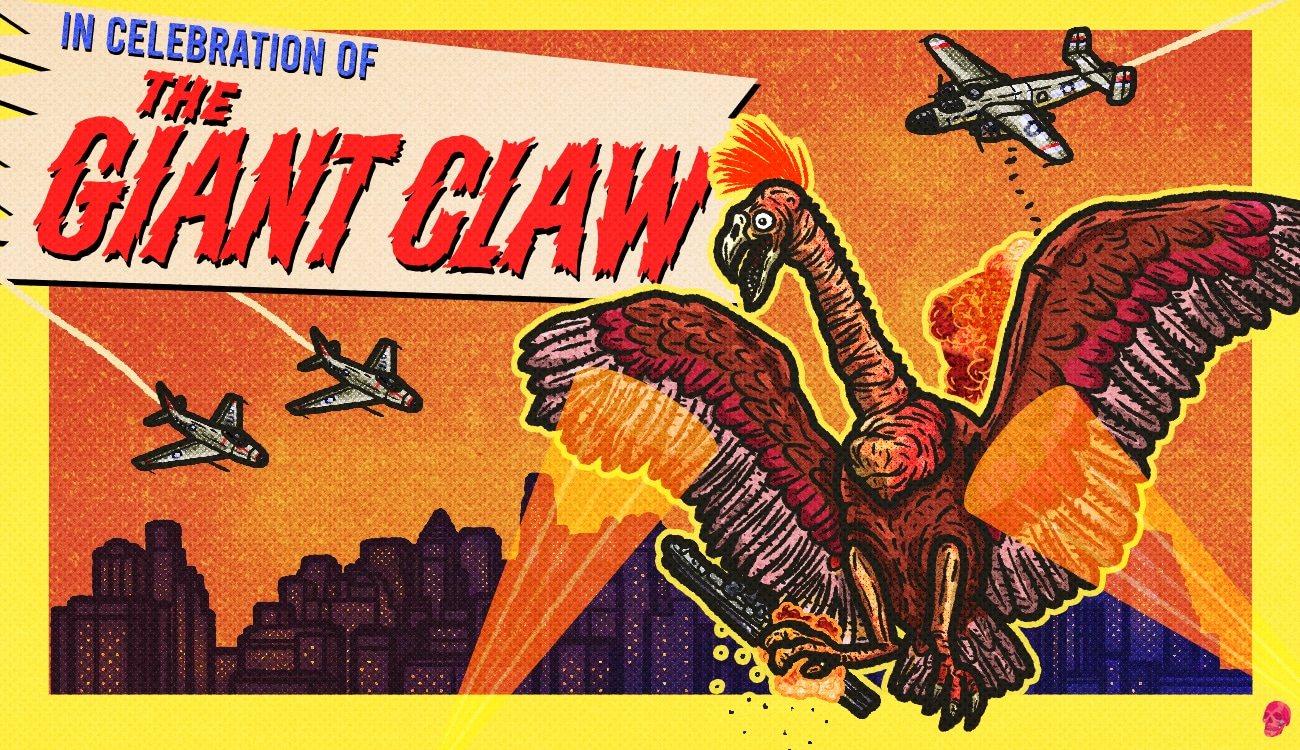

So, dear reader, what I offer here is an appraisal of The Giant Claw that seeks to offer a bit of nuance. As Criswell states at the beginning of Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959), “we are giving you all the evidence, based only on the secret testimony of the miserable souls who survived this terrifying ordeal.” All of this and more in celebration of The Giant Claw.

THE GIANT BIRD IN THE ROOM

For the uninitiated, The Giant Claw is a 1957 science fiction monster film about a giant bird, possibly from some “godforsaken” anti-matter galaxy in outer space. Having wrecked planes, trains, and automobiles, a plan is enacted to destroy the bird’s anti-matter shield so that conventional weaponry can kill it.

Most of the attention The Giant Claw receives focuses on its special effects. This isn’t surprising, per se, for the giant bird marionette is certainly a sight to behold. In an interview with Tom Weaver, Jeff Morrow, the film’s lead, recalled the following: “we poor, benighted actors had our own idea of what the giant bird would look like – our concept was that this was something that resembled a streamlined hawk, possibly half a mile long, flying at such speeds that we could barely see it.”

The actual bird has an elongated neck, flared nostrils, wild eyes, a mohawk of sorts, and extended legs.

All sorts of inaccuracies have run rampant about the bird’s origin and cost. Most common is the claim that the film’s producer, Sam Katzman, had it made in Mexico for $50. However, no source exists to completely verify that claim. In fact, Jeff Morrow himself joked that it cost “$19.28”. Interestingly, in the same interview, Morrow gives a ballpark price estimate for a “really good bird” at $10,000 to $15,000.

Morrow’s co-star, Mara Corday, also spoke with Tom Weaver about the special effects. She said that Sam Katzman had raved about “the wonderful special effects people in Mexico that he had hired” and that he’d allegedly spent most of the budget on the special effects. Was this just enterprising producer Sam Katzman exaggerating? Quite possibly. After all, fellow Columbia producer Charles Schneer – who had produced Earth vs. The Flying Saucers (1956) with Katzman – remembered him as being “skinflint” in an interview in Starlog #150.

In May 1957, Sam Katzman was interviewed in Variety, where it was reported that his films at the time cost between $250,000 to $500,000. While these films were made through Columbia’s B-unit, they certainly had more money to play with than other genre contemporaries.

And this is where the exploitation masters at American International Pictures (AIP) help to shed light on the dubious $50 claim. During their early years, back when they were known as the American Releasing Corporation, AIP had made The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955) with maverick producer Roger Corman. While the film’s poster depicted such a wild creature (it’s a truly fabulous piece of art), the first version of the film featured no such beast. The idea, of course, was that an alien mind creature had possessed the bodies of animals to be its eyes and ears, thus becoming the beast with a million eyes. This did not satisfy the film’s exhibitors, who had invested in the project on the basis of its lurid advertising.

Enter Paul Blaisdell, AIP’s chief monster maker in the 1950s. Roger Corman had turned to Forrest J. Ackerman (future editor of Famous Monsters of Filmland Magazine) to connect him with effects artists. Having turned down the suggestion of stop-motion maestro Ray Harryhausen due to cost, Corman was put in touch with Blaisdell. This would be Blaisdell’s first film job, having previously worked as an artist for science fiction magazine covers. Blaisdell took up the project, and was paid just $400 by Corman to produce an 18” puppet, nicknamed “little Hercules”.

The Beast with a Million Eyes cost just $30,000 according to Roger Corman, a far cry from the money Katzman was playing with at Columbia. Given that the marionette in The Giant Claw is far more sophisticated than that which appears in The Beast with a Million Eyes, it would be fair to assume it cost at least more than $400.

Of course, this is all conjecture based on incomplete evidence and contemporary productions, but it should illustrate that information is out there which allows us to report on these films with more detail than is usually afforded.

One last thing to examine is the ubiquitous claim about outsourcing the effects to a Mexican company. Although both Jeff Morrow and Mara Corday mentioned this nebulous Mexican effort in their interviews with Tom Weaver, the special effects are actually credited to three men: Ralph Hammeras, George Teague, and Lawrence Butler (who goes uncredited in the opening titles). As pointed out by genre historian Bill Warren, these technicians had all worked on more expensive A-pictures. Indeed, Butler is credited for special effects on Casablanca (1942), while Teague worked on the visual effects for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954). Granted, “special effects” credits at the time often referred to pyrotechnics and other on-set effects (as opposed to stop-motion, for example) but their involvement is still worth considering. So, who’s right and who’s wrong? Did Katzman indeed outsource to a Mexican company? We may never know, but by at least presenting “all the evidence” (as Criswell would say), we can understand films like The Giant Claw unbound from sensational or belittling rumours.

THE FILM AS A WHOLE

The Giant Claw is certainly no masterpiece, but it wasn’t intended to be. As Sam Katzman said in his interview with Variety, “a picture that makes money is a good picture – whether it is artistically good or bad. I’m in the five and dime business and not in the Tiffany business.” Indeed, the film itself is fairly standard in structure and form for a genre picture of its decade. There is the initial creature sighting, followed by disbelief, a second and more destructive appearance of the monster, realisation of its existence by the disbelievers, and a struggle for a means to destroy it.

The film leans into expository narration often, and stock footage from prior Katzman efforts like Earth vs. The Flying Saucers pads the proceedings. The archaic social dynamics of its day are also on full display. This certainly isn’t up there with the decade’s standout genre pictures like I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958), let alone better Katzman efforts like The Werewolf (1956).

But it is entertaining.

Mara Corday, star of other genre classics like Tarantula (1955) and The Black Scorpion (1957), is always a joy to watch. Unsurprisingly, she lights up any scene she’s in with a sly smile and smooth delivery. Jeff Morrow is a similarly pleasant sight for genre fans, having also appeared in This Island Earth (1955) and The Creature Walks Among Us (1956). While both Corday and Morrow’s other science fiction appearances handed them better material, they’re still very comforting to see in The Giant Claw. And while that comfort may be elusive for viewers unfamiliar with ‘50s sci-fi, Corday and Morrow have more on-screen chemistry than many of their contemporaries – even with the ugly veneer of ‘50s sexism and misogyny that’s peppered over the script.

And as for the bird? This author likes it. While the bird marionette is certainly goofy, it has a great deal of character in its wild eyes and constant shrieking. Indeed, its range of movement is rather impressive. Even though the bird almost certainly cost more than the flimsy claim of $50, this was still a low-budget picture made by a producer eager to save money. That the bird looks as animated as it does – eyes moving, nostrils flaring, etc. – is at least worth remembering. Moreover, we get to see lots of it, much to the chagrin of Jeff Morrow, who recalled shrinking into his theatre seat when the bird appeared on screen and the audience erupted into laughter. You can’t say you don’t get your money’s worth of the monster, even if it isn’t what you – or Jeff Morrow – were expecting.

As it stands, not every critic has been so harsh on the enormous bird. While the likes of Leonard Maltin have described it as “laughable”, the UK’s Monthly Film Bulletin commented that the special effects were “better than usual” when the film was reviewed in January 1957.

A FILM AS BIG AS A BATTLESHIP

While The Giant Claw certainly isn’t a shining example of ‘50s science fiction, it isn’t nearly as bad as some would have you believe – least of all because of its giant bird. However, exaggerated rumours and myths continue to circle. This does a disservice not just to The Giant Claw, but its contemporaries, too. Wild stories that sensationalise low budgets turn these films into little more than jokes, with scant consideration of all that went into them – let alone what they mean in their cultural landscape.

I’d argue that the various stories from the filmmakers and actors involved turn these films into fascinating artefacts, not all easily painted with the same brush. I don’t expect you, dear reader, to suddenly consider The Giant Claw as a masterpiece or even an overlooked gem. The film is still fraught with issues from the bafflingly complex origin of its monster to its ubiquitous stock footage. However, if we can consider The Giant Claw and its contemporaries on an individual basis, taking their often-fascinating production histories into account, we’ll have richer experiences when we watch them. We can also report more accurately on how films like The Giant Claw were made, referring to actual testimony (and some informed conjecture) rather than half-truths and rumours.

So, give another look to The Giant Claw, confident in the knowledge that there’s more to this bird than meets the eye.

A huge thank you to Daniel Hartles for providing this article’s accompanying artwork. You can see more of their work via their Twitter page.