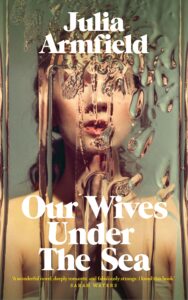

Something’s wrong with Leah. She returned from her deep-sea exploration weeks ago, but she’s troubling her wife, Miri, plodding around the apartment seeping water, spending days in the bath, and locking herself in the bathroom.

The book switches between the two characters — Miri, contacting her friends for some relief and being neglected by the enigmatic Centre which Leah’s expedition was a part of — and Leah, recalling her time under the sea surrounded by two crewmembers. While Miri tries again and again, through repeated calls and online forum visits, to see what has happened with her wife, Leah grows stranger, her symptoms worsening as the book deepens. Sections correspond to the ocean’s laters, starting from the benign “Sunlight Zone,” ending with the dark and horrifying “Hadal Zone.”

As Leah recalls her time stuck at the bottom of the ocean, losing track of time, Miri attempts to find the wife she once knew underneath the literal and metaphorical watery wall an unknown entity has erected in front of Leah. Combining bodily horror with an unnerving sense of realism, Our Wives Under the Sea is one of the most frightening of the year — no jumpscares required.

Our Culture chatted with Julia Armfield about her research from the book, the banality we meet with extreme events, and how queer relationships are portrayed.

This book terrified me to my core — this idea that someone coming back from the sea, thoroughly changed, is so scary. What made you think of this?

When I first started writing it, it was initially a short story idea. There’s a Lauren Groff novel, The Monsters of Templeton, it’s sort of about somebody coming back to their childhood home, and dealing with that in a sort of realist, personal level. But at the same time, there’s this monster that’s been found in the lake there. I love when people do the juxtaposition of realism and genre — I find it so interesting. I feel it’s a fulfilling way of dealing with everyday emotions. I knew I wanted to talk about grief, and I knew I wanted to talk about queer relationships. But I wanted it kind of smashed up against this weird thing going on. I’ve always been really interested in the way that when weird, shocking, or bad things happen, people don’t actually go on being shocked. It’s not like that H.P. Lovecraft thing where people keep reacting in horror at something. People always, I think, make an accommodation. I was interested in that — how the dailiness of everything would continue to assert itself over everything else that was going on.

Miri struggling to connect the Leah she had before with the one she has now is the main conflict of the book, while in Leah’s sections, she reminisces on her time under the sea. What was the effect of this disparity?

I always wanted there to be two voices — I always wanted it to be a novel that’s in conversation with itself. I see the narrative as one going up and one going down, as they go. I was thinking of a submarine while I was doing the narratives. It was sort of necessary as a way of talking about trauma, and necessary as a way of centering Leah very much in what happened to her. And then Miri being the tool in which I used to investigate everything else. I needed to spend an appropriate amount of time on what actually happened to Leah, and it felt like her plot line had to be distinctly that.

This is my favorite type of horror — instead of jumpscares or gore, it’s just this really unsettling and creepy tone through the book. Is this the type of horror you gravitate towards as well?

I have a broad taste, where horror is concerned. But the thing I’m interested in is the fact that horror itself is actually a relief. The thing that is scary is dread. Do you know what I mean Because it’s like, ‘This thing is gonna happen, it’s gonna happen, it’s gonna happen’ and it’s not happened yet — that’s the thing that freaks you out, when you’re waiting for the jumpscare. I always wanted to write a novel about that dread. Because I think so much of the novel — I hope — is about anticipation of something that happened outside of this submarine and you don’t know what. It’s also about an anticipation of grief and losing someone. I think that the dread of all that and the sense of not knowing is what I find really scary. I like most horror, so it’s not necessarily the only horror I’m interested in, but it was definitely the one I wanted to write.

The agency or organization Leah’s connected to, The Centre, is unhelpful and vague, which is especially annoying considering that Miri is just trying to help her wife and find out what happened. Was this place inspired by infuriating calls to companies previously, where you’re repeatedly asking for a representative and all you’re getting is unhelpful robotic replies?

That was very, very intentional — I think so much of it has to do with a smashing up of realism and genre against themselves. Obviously, so much of the horror is like, ‘What happened in the submarine?’ But a lot of the horror is just the clanging bureaucracy of not being able to get an answer or having the right password for the phone, or no one talking to you. It’s not dissimilar to dealing with companies or seeking medical care. It was very important to include people having very realistic reactions to bizarre things. Because actually, what would have happened is it probably wouldn’t be cosmic and fascinating — what would happen would be that you wouldn’t be able to get through to someone on the phone.

I thought it was interesting how in her calls to the Centre, Leah is almost a malfunctioning product to Miri, who is calling the company to find out what happened. She’s like, ‘Something’s wrong. I need help,’ when there’s no product guide for fixing a human.

I think that’s a really nice way of looking at it — I think you’re right. I can’t remember it, because I don’t remember my own writing, but there’s a bit where she’s, like, ‘Can you give her back better?’ or something like that. And I think it’s sort of tied to something which I really wanted to focus on, which is selfishness of grief. I don’t mean that in a bad way, but I mean when you’re grieving for someone, you are ultimately grieving for yourself without that person. Obviously, everyone is altruistic and when you love somebody, you have multifaceted responses to something. But a lot of what you are grieving for is ‘I no longer have what I have.’ So I think it had to do with coming to terms with the loss of a person even when they’re still there.

And I think that was why, when I was writing about that, I thought it was important to write about Miri’s past experiences with her mother, who has had this deterioration. Miri hasn’t dealt with it very well, and isn’t dealing with it well now. There’s a sense of coming to terms that, like I said, grief is selfish and that’s okay. You can’t control your emotions where love is concerned. And when you focus on something as a malfunctioning product, you’re still reacting to something in the realm of the fixable. So it kind of goes hand in hand with denial.

You are an evil genius for separating the book into sections representing the ocean’s layers, starting from the Sunlight Zone and ending with the Abyssal Zone. Chills literally ran down my spine once I realized what you were doing. How did you come up with that idea and where did you think to divide the chapters?

I remember sort of thinking about that, because in the acknowledgements, there’s this reference I have cited which is this interactive site where you can scroll through all the layers of the sea. It’s this illustrative resource where it keeps getting darker… Yeah, it’s quite disturbing. I remember seeing that when I was reading about the ocean a bit and I remember there being five different sections. I don’t get this very often, but you know when you just have a lightbulb moment, like, ‘Oh, this would be a really really nice way to structure things.’

I write completely chronologically. I really envy people who can go all over the place, do the important bits, and link them all together, but I have to do grunt work. I have to just hack through the novel as it will be on the page. In some ways it’s a very frustrating way to write, but also, it makes it quite easy to tell when you’re dipping down into a different tone or when something is getting worse. I think it’s also helpful for pace, because you can tell where things are going to be. So it felt quite natural, really to structure things like that. Because essentially, it’s a novel about things getting worse. I can’t remember if it’s the second or third section that’s quite a big rush of flashbacks, which I think is quite necessary to have nestled in the middle. But in general, it more or less dictated itself in terms of pace.

There are so many details that make the book insanely clever and well-rounded. What comes to mind is the online forum for wives to roleplay their husbands going to space, or a congregation called the Church of the Blessed Sacrament of Our Wives Under the Sea. How did you think of these small details that add some humor to this bleak situation?

I think it’s always necessary, to me, to have levity. I’m interested in the ridiculous quite a lot. I’m interested in when something terrible is happening, and yet, there’s always somebody focusing on something unbelievably irritating. There’s always somebody doing something bizarre. It came from the drive towards realism, I think. I’ve spent a lot of time on the internet — I’ve seen this kind of place. It felt natural to me that some people’s reaction would have been to join that exact website. The forum is Miri looking for some point of connection or something that will help her smashing up against something that’s really quite straight.

I think that was kind of what I was doing in a lot of other areas as well. The specificity of going through something as a lesbian couple and looking for something that is helpful, and the norm not necessarily being that, or people not necessarily considering that the norm, and how alienating and difficult that can be.

There’s a lot of different notes to that, and I think it just happens — when I was having surgery in November, and I remember my girlfriend was looking for something about it on the National Health Service. She found this resource that was basically for husbands being like, ‘When your wife goes through this, she might not want to do this and this.’ The way it was worded, like, ‘If your female wife doesn’t want to do this…’ This still happens! It was mainly levity. To a certain point, it was heteronormativity.

With Leah’s sections, we see her at the bottom of the ocean with her crew. How did you go about constructing details of a place that — I hope — you haven’t been before?

There’s some really great resources — there’s an excellent New Yorker piece about bathyspheres, there’s a really good Guardian longread about being hundreds of miles under the sea. But to some degree, it was less important to me to do high sci-fi. I love sci-fi, but I’m not explaining to you in great detail how the spaceship works, how the submarine works. It was more important to me to be in a situation which essentially felt like a haunted house. They’re trapped in this space, there are noises, there’s something about the space which is wrong. I was thinking more about The Haunting of Hill House when I was writing. At the same time, it was important just to do what needed to be done. I don’t want to take the piss when I’m putting something together — it needs to be believable. But it doesn’t need to be believable to a marine biologist, just to a man on the street.

I wanted to talk a little bit about the research of this book — so many times, when an author writes a book about a narrator with a specialized profession, it’s based on the author’s experience. For example, Hillary Clinton’s new book is about a fictional U.S. Secretary of State. Obviously, you were pulling from your own mind. You talk so much about the sea, but as you say in your note at the end, you’re not a marine biologist — what was the research process like? Were you always interested in the sea, or did this story just require more knowledge to tell?

I was definitely always interested in the sea. In my short story collection salt slow as well, there’s a lot of watery elements to it. In the last story, it’s like an end of the world oceansphere. But I think that in general, the research was fairly light. Like I said, I’m not too interested in everything being deeply provably accurate. I just needed to advance the plot; I didn’t need it to distract or say anything wrong. I’m really interested in horrible things, weird noises, glaciers carving, the way things look under the sea. To some extent, I could do research as long as it benefitted and interested me, which was nice because it meant that I could construct a book filled with stuff that I liked.

With some books, it’s clear the author just went on Wikipedia and researched whatever they’re talking about, and it ends up being dense and on the nose. That’s what I liked about this book — it was clear there was research, but it was never too dense; you just felt the presence of it.

That’s really kind of you. I think I wanted it to not wear its research too heavily, because I completely agree, I think you can always tell. You can tell when the author has done so much research when they’re loath to let go of something, and therefore they shoehorn the information in somewhere. You have to learn what is in your character’s voice, but you also have to learn what you just have to let go, even if you found something really interesting, because it might not serve the plot.

In your research, did anything surprise or shock you? Any cool deep sea facts you picked up?

This is really sad — did you know that I had no idea that the director James Cameron is one of the very few people who has been right to the bottom of the sea in a piloted craft? He’s one of, like, six people or something.

That’s really scary. I’m not a huge movie person, but that’s dedication.

I know! And when I tell people this, they’re, like, ‘Well, I guess he did direct Titanic.’ And it’s like, yes, but he didn’t do it there. It’s just very weird.

The book is being published later next month in the United States, and after that, what are your future plans? Another novel or project you’re working on?

Another novel, I think, at the moment. We’re at about 20k words, which my friend describes as having a little stew. Everything’s being cooked up, but it could still go disastrously wrong, so keep your fingers crossed for me.