The movies by anthropologist filmmakers Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel hinge on proximity. They survey unknown spaces, seeking intimate gateways into new environments and perspectives. With each work, intimacy arises by re-purposing the camera to obliterate the barriers between it and its subjects. In Castaing-Taylor and Paravel’s posthumanist masterwork Leviathan (2012), they adopt an aquatic GoPro camera, simulating the gaze of marine life (a literal fisheye lens). With Caniba (2017), an interview with infamous Japanese cannibal Issei Sagawa, they subvert the conventions of a talking-head doc into a blurry haze of extreme-close-up portraits, leaving us face-to-face with Sagawa. In their latest documentary, De Humani Corporis Fabrica, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel craft a bodily symphony on the modern hospital. Their custom-made surgical camera enters into patients’ bodies alongside the operating tools, broadcasting unprecedented images of fleshy interiority. They make visible the otherwise invisible depths of our corporality, conducting an acquaintance between spectators and the long-disavowed depths of our organisms.

The movie plays out like a digital-era update of Stan Brakhage’s The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes (1971): a silent, 16mm autopsy documentation. Yet as the title suggests, Brakhage’s movie isn’t just an archive of an anatomical disassembling. It’s also a film about the experience of vision. How do we gaze at sights of abjection? What are the limits of our identification with disembodied flesh? Like Brakhage, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel force their spectators into confrontations with the interior body. However, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel diverge from their precursor by focusing on living patients. There’s no escaping the pulsing vitality of these organs: the same mechanisms that regulate our own bodies. Castaing-Taylor and Paravel force a challenging identification between ourselves and the indiscernible caverns of tissue sprawled across the operating table.

De Humani unfolds across eight hospitals, drifting between an ensemble of perspectives. There’s the surgical eye, the testimonies of doctors, the perspectives of patients, and even footage following hospital patrolmen, stepping through dingy and graffitied subterranean infirmary tunnels. In an approach evocative of Frederick Wiseman (a fellow hospital documentarian), De Humani encapsulates the entirety of the hospital without any guiding narrational exposition. The movie’s vision is as expansive as it is eye-opening (ophthalmic surgery pun intended). Half of De Humani unfolds under skin. With their last couple documentaries, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel have garnered a reputation as film festival enfants terribles, inciting reliable floods of audience walkouts. Caniba and De Humani deal unflinchingly in the corporeal grotesque. Both movies centre on the terrain of flesh, albeit with opposing relationships. Where Caniba is harrowing, De Humani is moving. In Caniba, cannibal violence unfolds verbally, imprinted on Sagawa’s words. In De Humani, representations are explicit and the images are inescapable. Yet they’re hardly violent images. Instead, they’re often images of awe and affection.

A midpoint scene begins in sudden cut to cesarean delivery. Gloved hands draw an incision and then, like feasting children, tear open the skin. After the baby’s delivery, the camera follows in long-take as a nurse leaves with the infant and severs its umbilical cord. She cradles the newborn tenderly, speaking softly. Moments ago, it was erupting from a gaping abdominal cavity. Now, it rests. The sequence doesn’t present a reductive binary between “the violence” of the operating table and “the beauty” of new life. Instead, it reveals how these forces are intertwined, integral to the mediation of our biology. De Humani captures the proximity between these drastic moods, observing the operatic drama of the operating table. The movie also recalls the microscopic dramas of Hollywood microorganism-fantasies like Fantastic Voyage (1966) or—for my generation— Osmosis Jones (2001). In these movies, internal organs become battlefields. Though otherwise completely incongruous with Osmosis Jones, De Humani similarly fashions the body’s mechanisms into narrative. The surgery scenes tap into an unexpected tension, like an action sequence performed between sterile instruments and human tissue as doctors’ voices thunder from above, providing commentary. Castaing-Taylor and Paravel never lose sight of the stakes of the operations, selecting particularly critical surgeries where the line between life and death wobbles in the camera’s eye.

Yet these aren’t vignettes of pure spectacle or some morbid freakshow of attractions. Castaing-Taylor and Paravel move beyond abjection, observing how extreme surgeries unfold in relative nonchalance. During a urological operation, a tube is shoved up an anesthetized urethra. When it’s removed, a steady rainfall of blood pours from the opening. De Humani’s camera lingers on the bleeding while voices of surgeons trickle down, bickering about the minutiae of their work. In a corpse-dressing morgue scene, the workers make casual chit-chat and listen to pop music on the radio, all the while surrounded by dead bodies. For the medical staff whose day-to-day necessitates treating maladies and tiptoeing through the realm of death, the body ceases to be a spectacle. It becomes a workstation. De Humani’s proximity to the body, its maladies, and its death demystifies it, ushering us towards a newfound acceptance.

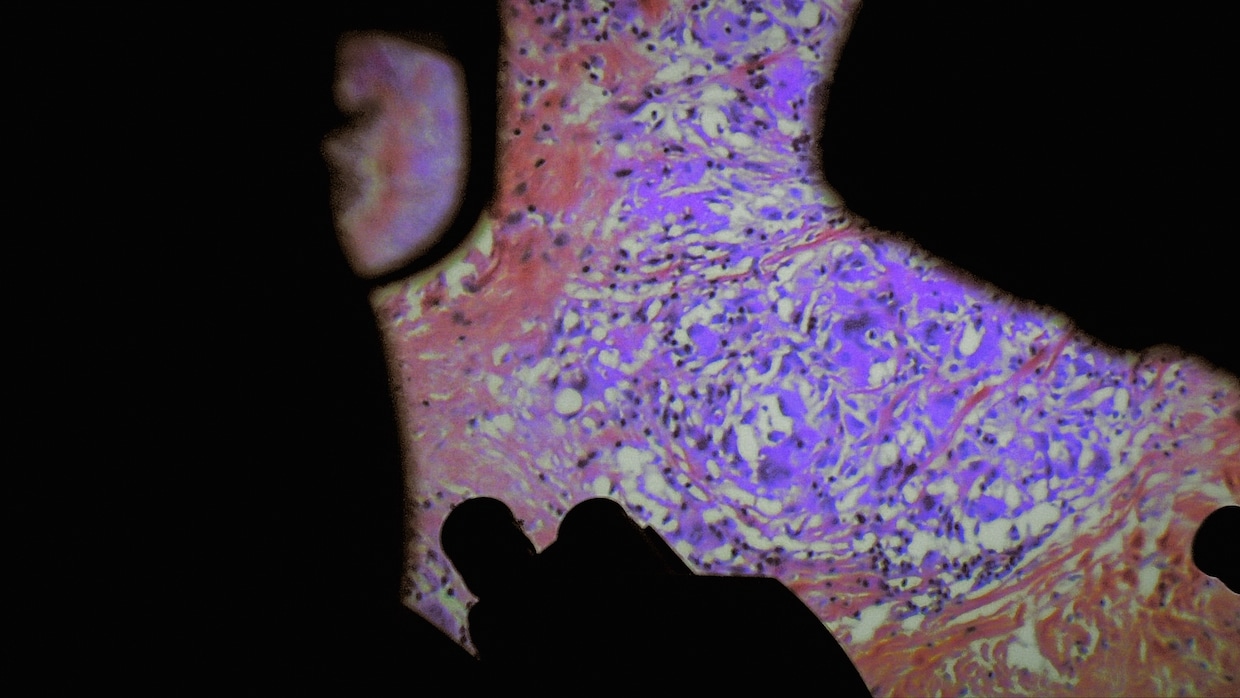

In the film, scenes often begin in the body’s interior, its fleshy, blood-filled crevices appearing like alien landscapes. The surgical camera prompts a dis-identification with the human body. It’s reminiscent of Castaing-Taylor and Paravel’s Somniloquies (2017), where close-up, out-of-focus shots of nude, slumbering bodies render their human anatomy (whether it’s genitalia or visage) indecipherable. Somniloquies and De Humani both dwell on unrecognizable representations of the body. In the tradition of Barbara Hammer’s Sanctus (1990)—which repurposes archival human x-rays into an avant-garde freeway of images— De Humani lingers on the inner canals and arches of the human body, broadcasting their flowing, abstract colours and textures. Yet the camera always pulls back from whatever orifice it’s plunged into (eyeball, c-sectioned abdomen, etc.) and arrives back on the surgery table. These moments of return incite a visceral identification with a previously abstract labyrinth of flesh and veins. The immaterial becomes material. And suddenly, we see ourselves on the operating table.