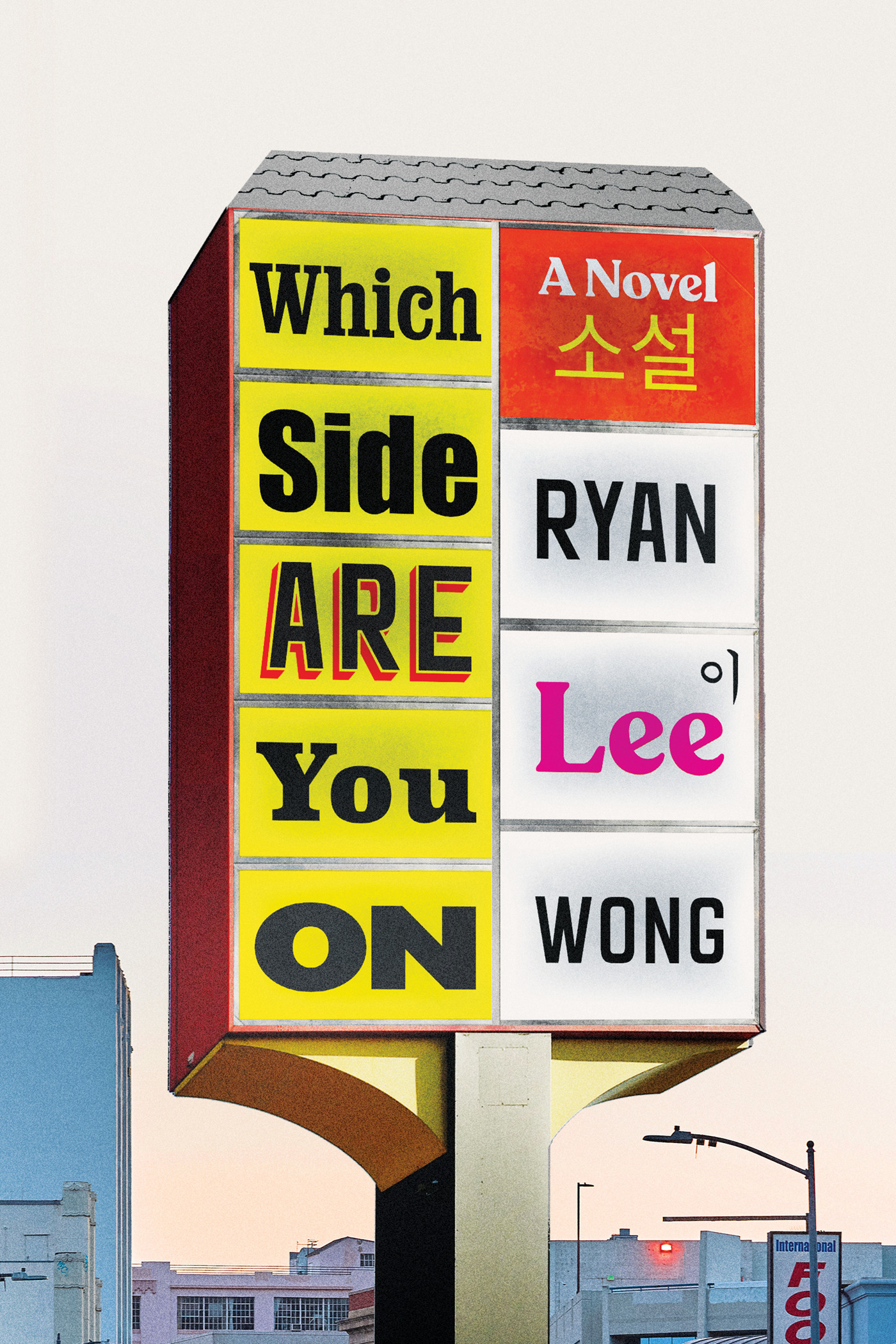

Reed, the 21-year-old narrator of Ryan Lee Wong’s debut novel Which Side Are You On, has it all figured out. After coming home from college at Columbia, he’s all too ready to teach his parents about how dining at one of their favorite Korean restaurants that employ Latino busboys unknowingly upholds “white supremacist patriarchy.” He learns about the world’s injustices not through his studies at Columbia, but from Twitter, which he cites as an unbiased news source and activist hub. As a recent college graduate who, similarly, must explain ideas and concepts that Generation Z know as fact but bamboozle anyone over 40, I related to this character and the blind confidence about the world that isn’t quite based in reality.

Following the real-life murder of Black man Akai Gurley by Chinese police officer Peter Liang and the political and cultural divides that come from it, Reed remembers his mother’s involvement in activism work and the Black-Asian coalition she was a part of during the era of Rodney King and Latasha Harlins. Reed meets with his mother, activists from her past, and starts to open up to the idea that there are other ways to organize, be politically involved, and function in today’s society.

Our Culture sat down with Wong to discuss his novel, the history that shaped it, and how generations approach activism and politics.

Congratulations on your debut novel! How does it feel to have it out in the world?

Good, good! It’s been a few months now, so it feels more normal and less like a whirlwind.

The heart of this novel is on the character’s arc, which was so clearly brought to fruition by the end. Was this the first element of the story you came up with?

The first thing that came up was the subject. I knew I wanted to write about these two historical moments: L.A. in 1992 and New York in 2015 and 2016. The character’s transformation had to follow from the historical record — I had to figure it out as I went along, and that was probably the hardest and most rewarding part of writing it. I knew the history was interesting, I had a personal connection to it, but actually figuring out what I wanted to say in a literary way was the great challenge of it all.

So we meet Reed at 21, on break from college, thinking he’s got the world figured out from his studies at Columbia and activism on Twitter. I definitely relate to this character, teaching my parents all the new radical ideas I learned at college and assuming they knew nothing. Was this character based on maybe a previous iteration of yourself?

Yeah, I would say partially a younger version of myself. And also the communities I was around at the time. I had a lot of experience with some of the activist communities in New York, and I met all these really brilliant young people whose analyses I really admired. But then also felt sometimes that they might hold the analysis above the human connection we were having. I think that’s something that happens to almost everyone in their politicization, so that moment was really interesting to me. That moment, of just being radicalized, seeing things for the first time, thinking you have all the answers for the first time and wanting to tell people.

This novel is based on the real life events of Akai Gurley, a 28-year-old Black man who was shot and killed by Chinese police officer Peter Liang. Reed is a Korean man, busy advocating for justice for Gurley, and wants to learn more about how best to proceed from his mother, a member of the Asian-Black coalition. This story is so rife with unfortunate history, from the events happening in present day, the Gurley case, and ones his parents are more familiar with like Rodney King and Latasha Harlins. This is clearly an important story to tell, and I’m interested in how you went about constructing this narrative that entwines multiple strands of history.

The history is based on real life. In real life, I was part of these protests around the Akai-Gurley case, and in real life, my mother was in these Black-Korean organizations in south L.A. in the 1980s. It was actually during that organizing work I was doing in Brooklyn that I really started to think about my mom’s history for the first time in a serious way. I actually went back and interviewed her, which was the spark of this novel. I realized it was such a rich history but not that many people knew about it, and it wasn’t part of the official stories of the L.A. uprising and Rodney King, so initially my impulse was just to get all this history down on paper and see how these events were happening in a cycle. It wasn’t that we were doing something that had never been seen or done before in Brooklyn in 2015, it felt like we were in a cycle of history.

Reed expects to know everything about how to organize and bridge the gap between two camps, one fighting for Gurley and one for Liang. I wanted to read this bit of dialogue between him and his mom, which is one of the most striking ways that their trains of thought differ. After a yoga session, Reed sarcastically says,

“Let’s address the racialized exploitation between Asians and Blacks by having them do yoga together.”

His mom says: “You talk, my smartass son, but things like that are how you actually connect people. That’s lesson one for your tool kit.”

Reed says: “Go on.”

His mom says: “Organizing is person-to-person, right? And do most people like to sit around in meetings talking about blah-blah racial capitalism? Or do fun things, like sharing food, or exercising, or listening to music?”

I feel like this is maybe the first moment where Reed starts to realize there are other ways to approach this problem, and that his mom has the experience to back it up.

Yeah, in my experience, when one has that moment of ‘waking up’ to certain kinds of violence or oppression, it can feel very serious and it can make one feel like they have to be serious also to meet that crisis or issue. When in fact, everyone I know who has stayed in movement work in a sustained way has found ways to make it joyful and happy and fun. And that’s just as helpful to building as theory and the critique.

Something I’ve been thinking about recently is that prioritization of the self isn’t necessarily selfish. Reed feels shame, whether it be from himself or his friend Tiff, for attending a salon appointment his mom organized, because he feels he should be out there learning and being an activist. Talk a little bit about this moment and what it means for Reed’s overall story.

There’s this other idea that I think a lot of people internalize is that to do nice things for oneself is a betrayal of the movement or self-indulgent or reinforcing capitalism. On some level, that is true — it is hard to care for oneself outside of capitalist forces. And yet not caring for oneself, in my view, reinforces capitalism because it treats bodies as disposable and machines. What Reed has to learn is to accept certain ways of existing within these systems without giving them more power by taking them as absolute truths or being paralyzed by not being able to act under such forces.

I liked this line from Reed, which gives sort of a truth to younger activism work: “I wanted to be a radical, but I wanted it my way. I wanted credit.” Do you think that we have a problem today with people who do activism simply because it’s visible and virtuous? Did you ever want to explore performative activism further in the novel?

That’s definitely a sub-theme in the novel, and Reed has a conversation with his dad later and says that performance and politics are really almost inseparable for our generation. I think this is true largely because our identity is so bound up in how we present to the world via social media. From a very young age, we start to craft these personae, and your politics is part of this persona. What Reed is confused about is that he actually is driven on some level by ego. Even though consciously he thinks he’s being really selfless and putting his whole life to the cause, he’s actually being driven by an individualist desire to be recognized as good.

I love that this is a coming-of-age novel set in a relatively short span; he decides to drop out of college, changes his mind, meets activists and discusses with his friend about what he’s doing. For a culture riddled with confirmation bias and radical ideas, this is honestly a hopeful look at how we examine ourselves and our families, and how we can come around and compromise. Did you set out to end it this way, or was this the logical progression of Reed’s story?

The main thing that had to happen for me to finish the novel was to have enough distance from Reed, both so I could capture his voice and what that age was like, but also distant enough so that I could have some compassion towards him. The point of the novel isn’t that he’s a jerk or idiot, the point of it is that there’s some of that in all of us. The only way to move forward is to bring compassion to oneself to that mind that wants to do everything right, to other people who maybe don’t have it right, in your worldview, because ultimately relations are more important than your idea of a revolution. There’s no change without the people around you.

Finally, what’s next for you? Do you want to continue political writing or other avenues?

It’s a little too early to say, but I have ideas for other projects, both fiction or nonfiction. I really am interested in the themes that were brought up in the book — questions of how we build community when we’re so fractured by technology and political divisions, and disagreements about truth. I’m interested in talking about my Zen Buddhist practice, which was a big shift in the course of writing this novel, which shows up in little ways. And I’m also interested in these larger questions of radical history and politics and movements, which often don’t get that much attention in literature.