What are you amused by? a crisis

Frank O’Hara, “Ode”

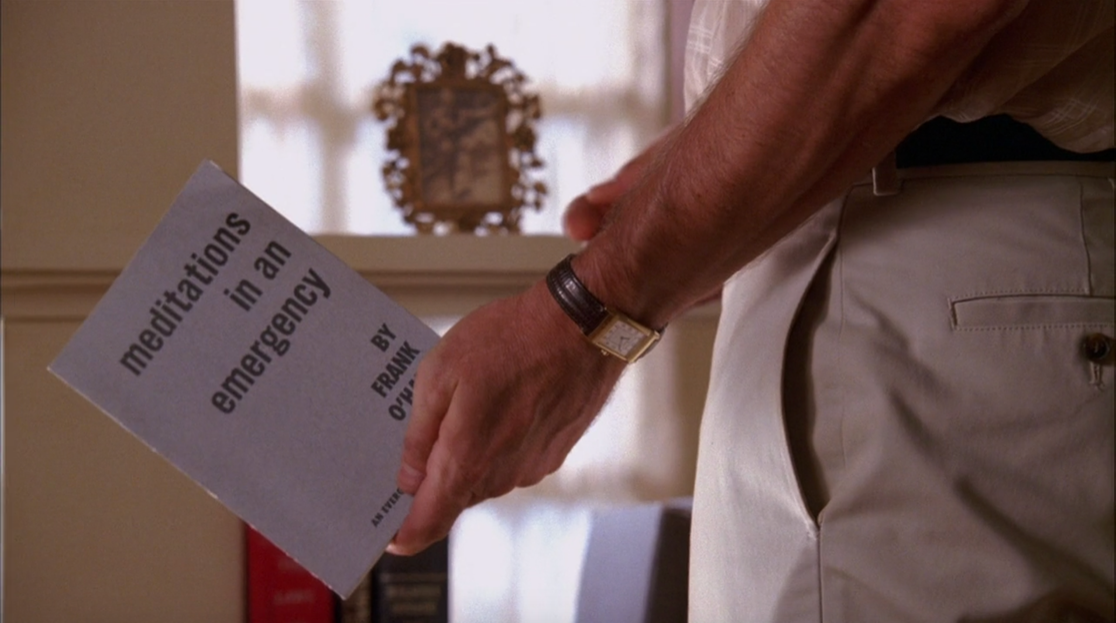

Don Draper sits at his desk at his home in Ossining, New York. In this desk are his secrets and an obscene amount of cash. He’s reading Frank O’Hara’s Meditations in an Emergency, and he finishes the book’s final poem, “Mayakovsky.” We hear him recite the final stanza as he writes a note at the top of the page, “Made me think of you.”

The stanza goes:

“Now I am quietly waiting for the catastrophe of my personality to seem beautiful again, and interesting, and modern… It may be the coldest day of the year, what does he think of that? I mean, what do I? And if I do, perhaps I am myself again.”

It’s dark out as Don mails this book to an unknown recipient. He’s walking his dog that we all forgot he had.[1]

In 1962, we’re barreling towards the Cuban Missile Crisis whether we know it or not. Nuclear power’s only obvious promise was oncoming crisis, and the October Crisis of 1962 does hit in a certain way today, in 2023. Nearly 2 full weeks where the expectation is full-on nuclear warfare, and the only way to learn more about what’s happening is to watch the news or listen to the radio at certain hours of the day. There’s no 24-hour news networks, much less the constant breaking news of online media. You’re waiting for the news, waiting to be told what to be afraid of and how to be afraid. All one can have in the time in between is their wits about them, either to keep them sane or do the opposite.

New York City life is hectic. O’Hara knew that. Meditations in an Emergency is about New York in some big way. When it’s introduced in the show, a random man reading it at a bar over lunch tells Don that he wrote some of it “here[2]… some on 23rd street, some place they tore down.”

The clichés about New York do end up to be true – there is a bombastic and ecstatic energy that runs through the city in its most alive moments. It takes a fair amount of energy to function through the noise, and when a city of millions is all collectively doing that at the same time, it’s a game of mutual escalation. Meditations often match and challenge that energy. O’Hara has these sporadic and staccato bursts met with swinging vocabulary. He’s focused on what he’s evoking, it seems, more than he’s focused on following any specific subject or through-line. There’s a frenetic pace of thought, one that I personally found to be confusing, demanding of a re-read. Some of his poems feel easier to understand than others, but what’s understood more than anything else is the book’s feeling in its totality. The sum is greater than its parts, in that way.

O’Hara dedicated Meditations to Jane Freilicher, a painter and contemporary in the same artistic movement O’Hara considered himself a part of, The “New York School.” Poets, actors, dancers… artists who subscribed to a certain sense of the avant-garde as it was understood in the 1950’s and 1960’s. I do not know that I have the space in one essay to fully define what that means, “avant-garde,” but as I understand it, the effort is to be unusual, unexpected. To represent some kind of abstract feeling over representing a certain reality. I don’t know that I feel qualified, either, to deem Meditations successful in that endeavor. There’s absolutely something urgent about these poems. They can feel so scattered, even standing next to one another. O’Hara’s tendency to free associate almost at certain points creates this frantic space for the poems to live in, as if he were to have edited diary or journal entries with a heavy pen. He’s often so public about his personal, so unwavering in waiving his own privacy – an uncommon and radical openness. It’s not surprising, then, when the stranger in the bar tells Don Draper, “I don’t think you’d like it.”

Mad Men’s second season opens with Chubby Checker’s infectious voice as we watch the characters get dressed. It’s the opening to “Twist Again,” and the lyrics ask that we do it all again like we did last summer, like we did last year.

Sterling Cooper’s first Xerox machine arrives in the first five minutes of the season’s premiere, but Mad Men does resist repeating itself in its sophomore outing. Still, its overall movement, interestingly, is nearly null. What we’re dealing with in 1962 is the fallout of what we dealt with in Season 1, which closed on Thanksgiving 1960. That is to say, in the show’s second season, Don doesn’t become uninterested in his marriage, he becomes even less interested in his marriage. Pete Campbell’s allegiances to Don, to himself, to the company only get tested further.

Peggy’s entire Season 2 arc is built to deal with Season 1. We spend so much time with her and her family, her and her church, and we’re not barreling to any kind of religious realization about what Peggy wants from her family, or from her god, or how those things intertwine. What we move toward throughout 1962 is Peggy’s confession to Pete about their illegitimate and now orphaned child that she had in Season 1’s finale.

Season 2 of most television shows is a wash. Think about it: the first season of a show has no constraints over its conception. As much as the television industry runs by buying pilots, showrunners and TV writers, and Matthew Weiner especially, have some idea of how the full season looks, what the arc of the main character is, what they want it to look, sound, feel like. You could spend a lifetime writing a pilot that sets up these ideas and plots. And then, if you do get so lucky, and Season 1 does get written and produced, and the network buys another season, the second season has to be conceived, written, and produced within a year. It’s an efficient system for releasing television, but not always for the show’s story.

Matthew Weiner, the show’s creator and head writer, has spoken before about the influence of various novelists and poets from the 20th century on Mad Men. Something about the sound and feel of O’Hara’s poetry, specifically, contributes to the unmistakable tone of Mad Men on a sentence to sentence level. Dozens of lines throughout Meditations reflect Mad Men’s second season.[3] Not even so much as a mirror. More in the way of looking at an old photo of yourself and remembering how it felt. That feel like they reflect certain happenings in the season. In “Poem,” the book’s second, O’Hara writes, “There are few hosts who so thoroughly prepare to greet a guest only casually invited, and that several months ago.” Who, of course, is more gracious as a host than Anna Draper, to whom Don sends O’Hara’s poems? Not only hosting him in California, but hosting his being in her late husband’s name.

I’m reminded, too, of what Bobbie Barrett says to Don as they start their illicit relationship. Don calls Bobbie with his wife and kids in the other room, and he tells her this. She says, “I like being bad and then going home and being good.” O’Hara’s version in “To the Film Industry in Crisis”: “And give credit where its due/ not to my starched nurse who taught me how to be bad and not bad rather than good.”[4]

These comparisons genuinely go on long enough that I have to stop myself, but I’ll share one more to make the point, and then I won’t do so again. After Bobbie and Don crash a car in a drunk driving accident, Don calls on Peggy help clean up the situation, bring him cash to bail him out and take care of Bobbie until her eye sufficiently heals. Peggy owes Don, she knows this but we don’t yet, and neither does Bobbie, and she’s very concerned as to why Peggy is helping him. Bobbie develops a kind of respect for Peggy, if not one doused in heavy skepticism. Bobbie is an older woman who has made a way for herself in an industry where that’s not common, and Peggy decidedly[5] hasn’t. She tells Peggy, “And no one will tell you this, but you can’t be a man. Don’t even try. Be a woman. Powerful business when done correctly.”

In O’Hara’s poem to James Schuyler, he repeats and repeats and repeats again, “I could never be a boy… I could not be a boy.”

“Meditation” does feel like a word we all inherently understand. There’s some collective image we all have of what meditation looks like. The crossed legs, maybe a humming tone. There’s the sort of advanced, next-level general knowledge of mantras, repetitions for the sake of gaining focus and perspective. The roots of “meditate” are closer to “heal” or “cure” than it is to “think.” People who can meditate, those who are capable, would probably agree with the notion of the word’s roots. To abstain from work of living your life, even for only minutes at a time, probably is quite healing.

As overwhelming as Frank O’Hara’s New York can be, as complicated as it can be “out there,” the characters of Mad Men are often seeking solace from that inside the office. One of the main criticisms railed against Mad Men was its similarities to a soap opera. The sense of melodrama, the conflicts throughout the series are basically completely interpersonal. These are not high, high concepts. It’s not the intended message of the show, maybe, but an argument Mad Men ultimately makes is the use of work as a sense of meditation from the outside world. Personal problems are always present, but there’s also always work. Throughout season 2 especially, Peggy seeks solace in work amidst the chaos outside. Between pressure from her family and her family’s church – there’s pressure to perform at work but at least that work is concrete. Peggy knows what she wants inside: more respect from her coworkers, more assignments from Don, an office if it ever opens up. There’s a comforting rigidity to moving up the ladder of success.

Chaos, though, is abstract. It lacks edges, borders. When the office devolves into chaos over the final few episodes of season 2 – as a pending merger looms, as the Soviet Union approaches, as Don is still nowhere to be found – the pretense of polite society and appropriate conversation for a work environment drop completely. It’s the end of the world, Peggy, now is the time to confess your sins, says Father Gill. It’s the end of the world, Peggy, I should have married you and not my wife, says Pete Campbell. The frenetic pace of the outside, the kind that Frank O’Hara captures, makes its way into the walls of Sterling Cooper.

I, too, am writing from an emergency. Going on year three or more depending on how you’re counting. The coronavirus pandemic hit New York City, apparently, in February, when I was spending a lot of time on the Upper West Side and finally starting to get my footing. Within the first month that it started to get really bad, it circled around online, ad naseum, how Shakespeare wrote King Lear during the last global pandemic. This was shared under the guise of, “Now’s your time.” “You’ll never have more time to start that project.” Things your mother would say to you if you ever expressed any latent interest in art. Or any interest at all that didn’t fit into what your life started to look like.[6]

I did write more during the pandemic than I had in years. I did not write every day, and I did not write because I felt compelled to do so or because I was pulled by whatever spirit it was that conceived a story as dramatic and interesting as Lear. I wrote more because I had to do something to kill as many minutes as I could. There’s no subtext to me in that, or at least there’s none intended. This was not something to do for fun, or even something that I feel I did successfully, but because there was nothing else to do.

Work persists. An abhorrent, abject reality. We always have to do work. There’s always work to be done. I don’t know how we are all expected to continue to work every day. To sound exactly like my age, exactly like my demographic: if we’re all collectively making this up, all the time, as we go, why would we make it so hard on one another? How are we all so constantly in each other’s way? Somehow, the answer to that question strikes me as both, “it’s no one’s fault,” and “it’s everyone’s individual fault.” And I, too, feel reflected by O’Hara in his poetry, in his boundless swaying from bullish optimism to growing despair. In the titular piece, Meditations, he writes, “I am the least difficult of men. All I want is boundless love.” He manages to say this with a wildly admirable sense of hope, only to undercut that hope later, writing, “No one trusts me. I am always looking away. Or again at something after it has already given me up.” In the poem’s final stanza, O’Hara simplifies this dichotomy even more: “I’ll be back, I’ll re-emerge, defeated, from the valley.”

I love this. Brand new in the same way every time I read it. Returning, re-emerging, defeated, from the valley. What else is there to do?

Don returns from California at the end of Season 2 and Duck Phillips, the head of accounts he hired, has set the wheels in motion on a merger with a much bigger company in Putnam, Powell, and Lowe. The terms of the deal aren’t clear to me, a rube, but what is clear is that Don’s role, his importance to Sterling Cooper, is diminished a great deal. In the meeting where he returns, Don reveals to Duck that he’ll leave if such a deal goes through, that he isn’t under any contract that holds him to doing so. Just before he leaves the meeting, he says, “I sell products, not advertising. I can’t see as far into the future as Duck, but if the world is still here on Monday we can talk.” As long as there’s another week, there’s more work to be done.

Not to steal a sentiment from the syntax of the internet, but I feel what Frank O’Hara was saying when he said, “The country is grey and brown and white in trees, snows and skies of laughter always diminishing, less funny not just darker, not just grey.” We as a people are not built to exist through a years long emergency. What a grey time this has been, continues to be. It was within the first month of the pandemic that we all learned the phrase “essential workers.” Doctors, nurses. Public services. As we learned more, things became more essential again. But through that whole period, those first few awful months, we were all just told to work through it, and if your work was taken away, you were told that now was the time to do the work you really wanted to do. As much as this is abrasive to me, I have found myself experiencing a profound sense of gratitude over the last years when I have had any work to do. A chance to escape myself, to let myself heal in increments however minor. Recharging in the emergency, moment by moment. Waiting to become myself again.

[1] Her name, the dog, is Polly.

[2] I have tried desperately to figure out where “here” is and I cannot.

[3] Not only in that the book’s title returns as the title of the season’s finale.

[4] Consider, as well, that said poem is about a certain love for film, one Don shares when Barrett asks him a simple question he has trouble answering: “What do you like?”

[5] “Decided” by Bobbie

[6] The first recorded COVID-19 death happened in March at the hospital down the street from me in Bushwick. I had been there a month before with extreme flu like symptoms, but after more than one test they concluded that I didn’t have the flu.