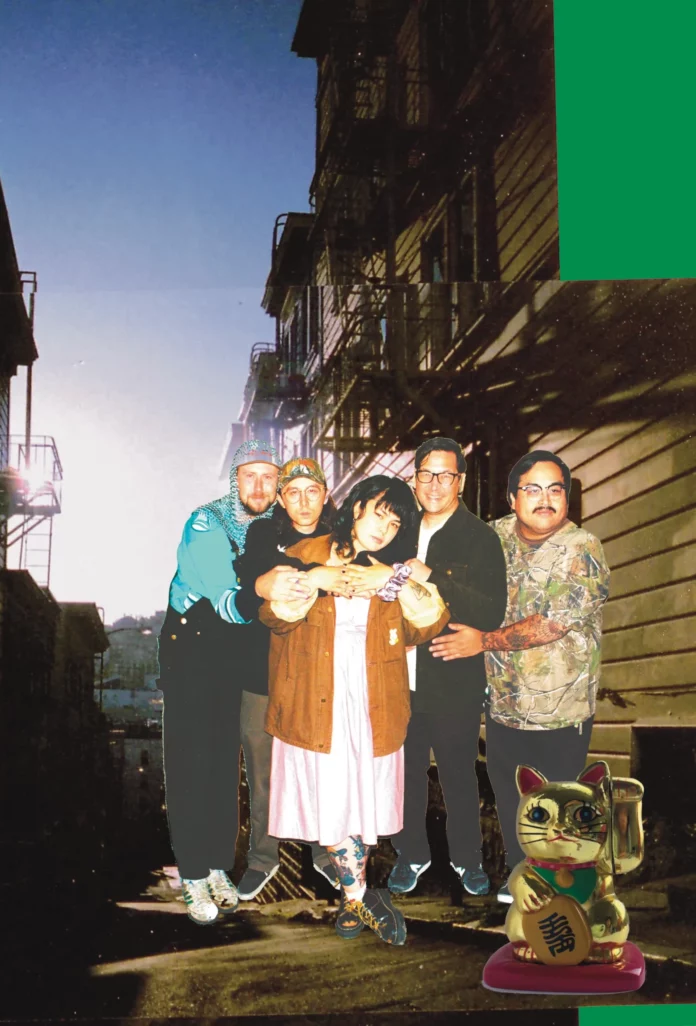

Star 99 is a San Jose band formed by Saoirse Alesandro, Jeremy Romero, Thomas Romero, and Chris Gough, all of who grew up immersed in the South Bay’s indie punk scene. Alesandro had been writing songs ever since she started playing guitar as a teenager, but unlike her bandmates, she’d never been in a band before. After releasing their self-titled EP in July 2022, Star 99 came through with their debut album, Bitch Unlimited, a year later via Lauren Records. Now, with the addition of multi-instrumentalist Aidan Delaney, they’ve leveled up on their sophomore LP, Gaman, which is out today. They’re still making punchy, exhilarating songs while pushing beyond – though not necessarily past – the twee sensibilities of their debut, making way not just for the confrontational nature but the poetic nuances of their songwriting. As Alesandro and Romero trade vocals, revealing the core emotions that bind their songs – insecurity, resentment, isolation, often fueled by the fire of generational trauma – you get less of a sense that these are separate people bringing songs than just two friends, in a band, facing similar strifes – and getting through them. Which is, definitionally, the art of gaman.

We caught up with Star 99’s Saoirse Alesandro for the latest edition of our Artist Spotlight series to talk about the name of the band, their dynamic, the making of Gaman, and more.

SEO is weird – when you search Star 99, the first thing that comes up is thankfully your band. But if you type something like “Star 99 shows,” you get this radio station, and I was wondering if there’s some connection with the name.

The band named after a porn shop where we grew up, near San Jose, that none of us were old enough to go to. I don’t even know if they were aware of it, but I’d pass it all the time. It was this bright blue and pink building, and I thought it looked cool. It said it had VHS tapes! They had VHS tapes. [laughs] We just named it that. I thought it sounded cool, but yeah, it’s not very Googleable. I’m grateful the porn shop doesn’t come up. It’s closed now.

It’s funny because the radio station specializes in “uplifting and family-friendly Christian music.”

[laughs] That’s hella funny. I think we strive to be family-unfriendly and a bummer, so maybe the opposite.

Well, the press release does say, “Star 99 makes music for their friends and families.”

Oh, yeah, dude. Music for your family is not music to make them feel better. [laughs] It’s kind of expository, especially Thomas’s songs. He’s from Guam, and his songs are about family trauma and generational trauma, crazy role models, all that. I’m really proud of him for talking about that stuff because it was hard for him to talk about it for a while until he wrote songs. Definitely not trying to make them feel good – sometimes people don’t deserve it, man.

Was it something he talked about with you before writing about it?

Honestly, band practice is kind of a place to air your grievances. Healthy or not, it’s like group therapy. Often, it’s the only place I’ll talk about my family, what’s going on with my mom or my relationship with my dad. Same with the rest of the band. A lot of the record was informed by those conversations we’d have before practice or on tour because everything comes out in the van. He’d talk about it, but not as much because when he’d bring lyrics to practice, we’d be like, “Whoa, are you cool? That sounds tough. What is this about?” It creates a unique platform to jump off from – it’s harder to bring that stuff up cold.

Do songs ever come out directly from those conversations?

Thomas will show up to practice with a song mostly done. We both write at home and bring a song that’s like 70% done to practice, then show it to each other acoustically. Once everybody understands the emotional place we’re coming from, we’ll write the rest of it. It’s freeing because when we’re writing all together, it’s not just my thing anymore. It’s way less precious. I can take stuff and chop it and move it around, which I couldn’t do without a lot of trust in them. You get really attached to songs that are so personal.

Did the start of your friendship coincide with the formation of the band?

The band came way later. The band was – we missed each other during COVID, and I moved back from LA. I wanted to hang out with them, but it was COVID time, so we were like, “We need to be a pod.” The band was kind of an excuse. Jeremy, the drummer of our band, has been going to shows since he was 12. My dad was playing in ska bands and punk bands forever on Asian Man Records. We all met through Asian Man Records, packing records together. I met Jeremy when he was 14 or 15, and I was in high school. I met Thomas on a train, eating pizza. [laughs] It was about a year after he moved here from Guam, totally alone. He moved to San Francisco at 19. And then we all ended up living together. Chris was Jeremy’s boss at an Indian food restaurant, and Aidan – Jeremy went to high school with him before he dropped out. So Jeremy’s really the glue, the common denominator.

How naturally did the conversation lead to Star 99?

Jeremy, too! It’s funny. I was writing songs by myself forever, and Jeremy wanted to start a band together. So he said, “I’ll just play drums, and it’ll be great. We’ll just hang out and play your songs.” I was like, “Okay, that sounds scary.” But it wasn’t, and it came really quickly. There was no other option in my head – nobody that I wanted to play music with other than them. It felt really natural. It just felt unnecessary and intimidating with anyone else, but with them, it felt like hanging out. We’d already seen each other cry and argued before, so I was like, “Okay, this will be fine. No risk.”

Had it crossed your mind that you wanted to play these songs you’d been writing with a band?

My dad put that in my head since I was a kid. He’d say, “You just need to start a band. That’s where the real magic happens with songwriting, when you have a band dynamic.” I was like, “Okay, that sounds annoying. I could just do it by myself.” I never played in a band other than this one. Not them – it’s their third or fourth band, but for me, it’s my first. I’ve been writing songs since I was playing guitar, which was 13, but they were kind of just a way to write poems. What I really love is writing poems, and this is just a vehicle for poetry – and making flyers. I love making flyers.

It sounds like music was a big part of your family and social life, but it was also something that, at least when it came to songwriting, you wanted to keep private. Was there a separation between those two worlds for you?

That’s a cool question. I saw people who played in bands as a totally separate thing from what I was doing. I’ve been going to shows for so long, since I was, like, born [laughs], because of my dad, which I’m thankful for. But it was kind of his thing, and honestly, sometimes it felt like a thing for dudes to do. Which is super incorrect – I’ve seen a lot of great female musicians, but it just felt like something I wasn’t going to be good at. It’s like, girls that can play guitar really well, or a bunch of dudes, so whatever. I kind of wrote it off, and I went to illustration school and became a graphic designer.

But when I started playing in this band and playing loud – I’d never played guitar loudly before – something really clicked. I was like, “Oh, this is magic, actually. This is my favorite thing I’ve ever done.” And that’s still true. It’s my favorite thing. I complain about it all the time – right before a show, I’m like, “I hate this. I should never have done this, I can’t believe I’m doing this again.” But it’s the most satisfying experience to finish a record, feel proud of it, and feel like you did all you could do. I couldn’t do that by myself. I needed them. That’s community, and it’s really fucking beautiful and radical and political. There aren’t a lot of experiences like that.

What are some of your earliest memories of showgoing?

Dude, ska shows. A lot of ska shows because my dad was in a ska band. But I saw Lemuria at 12 or 13, and my brain chemistry changed. They’re probably my number one influence forever, just because she was so uncompromising and so good, Sheena Ozzella. I’d never seen a girl who talked like me, or felt approachable, or was funny or normal, play music like that.

Aside from the communal aspect of being in a band, there’s also a conversational quality to Gaman specifically, a kind of back-and-forth between the songs you sing and the ones Thomas sings. Is that quality something you talk about, that’s palpable in your process, or maybe later while sequencing? How do you approach it?

We don’t write them in the order that they’re in, so it’s not so direct. But because we’re always talking about the subject matter, it comes up naturally. Thomas’s songs are similar in that we’re talking about generational trauma and how, as generations progress, the way we interact with trauma and strife changes, so that creates intergenerational discord between parents and kids. That’s all similar, but I think Thomas has a totally different set of experiences than I do, coming from Guam. There’s cultural differences – I’m Asian American, mixed, and from here. Totally different parent figures and relationships with our parents. It’s kind of weird, but Thomas and I have the same birthday: June 11. We’re like Gemini twins, so we celebrate our birthdays all the time. I’ve always felt this – he’ll hate this [laughs] – weird throughline with our brains. We’re pretty in sync, even if we’re not talking about it. So that dynamic comes up naturally.

The song ‘Gray Wall’ is fun because it catches you off guard with that drum beat, but it’s also the first time your voices come together in that way on the album. What was it like when you came up with that song?

That was a magical writing day. It was the last song we wrote. We had this drum track my partner made for us, and I was like, “We’re not gonna use this, this is dumb. We have a drummer!” [laughs] But we wrote to it on the spot. Everybody was there, and we wrote the lyrics, words, and melody in like an hour. It was really fast, and we never write like that. It made something kind of weird, which I’m glad we kept.

You talked about music being a vehicle for your poetry, and that’s a quality I latched onto on a lot of the songs. I love the way you describe imposter syndrome on ‘Emails’: “I coast on implications of talent/ I hope no one can tell I don’t have it.” Could you talk about how these feelings affect your process or your place in the music world as a group?

I think nobody in the band fits into a constructed, conventional idea of DIY or subculture. But in that way, everyone fits in. It’s a bunch of misfits together, which is what DIY is. That’s what it means to exist in DIY: finding community in your otherness. Those moments where you feel like an outsider among others are terrible. I’m like, “Okay, I can go to work and no one’s going to get me,” but when I feel like that at a show or in the subculture I choose to be a part of, it feels terrible. It’s all related to gender and non-whiteness. That’s what we all have in common, right? We’re not big white dudes in punk. We’re just not, and we don’t sound like it either.

How do you show up for each other through those feelings?

I grew up with my dad, and I’m a sister with brothers – I always felt like a girl first, younger first. But with my friends, I don’t feel like that. I’m not pushed into a corner that I see some people get pushed into, of being the femme member of the band. You’re isolated. I feel equal because we’re all friends, and it’s never been anything but that. It’s been extremely safe for me to air – when a sound guy doesn’t think I’m in the band, which has happened, or when I go to the guitar store and they ask me what I want to buy for my boyfriend, or when some dude hits on me at a show and they all have to get me out of a really shitty situation – they see that. They see that we have different experiences based on how I present, and I don’t need to explain it to them because they see it. I do explain it to them all the time, but I don’t really need to. [laughs] And to not feel like a bummer for bringing that up is cool. The bar is so low, I don’t know.

The title track is the last song on the record, and the quietest, but also the angriest, and ultimately maybe the kindest. What does it mean for you to end the record with it? What feelings does it leave you with?

That song makes me sad, still, for sure. It’s about my grandma, who is like a mom figure. We grew up with her – she’s still around, she’s cool. She’s Japanese and was in the internment camps here. A phrase Japanese people, especially Japanese Americans, use a lot is “gaman,” which means pushing through despite adversity. People used it as a mantra in the camps, but my grandma uses it every day. She keeps a solid front, a happy face, despite going through so much shit constantly. As we get older, Thomas and I talked about how we start to embody qualities in our parents that get us through stuff, but we also reject coping and defense mechanisms they used that we don’t need anymore. Part of gaman culture is not talking about stuff, pushing through, and keeping your head down. I’ve clearly rejected that. [laughs] I’m Japanese American and mixed, but I can’t do that – I have to talk about everything. Maybe that’s being Irish, I don’t know. I love therapy, I love talking to my friends, I love calling my parents out. That’s the thesis of the record: the stuff we’re choosing to take with us and the stuff we’re choosing to leave behind because it doesn’t serve us anymore.

Do you mind sharing one of your favorite things about each member of the band?

Chris, who plays bass, is a true believer in DIY. He books shows, still, he goes to them – and they’re, you know, varying degrees of quality. Don’t tell him that. [laughs] But he’ll go to everything. He books a lot of kids who play in the Bay, and that’s a tough job. He’s a real DIY lifer, and I look up to him a lot. Jeremy, who plays drums – if I’m lost, like, in the world, emotionally, or geographically even, I go to Jeremy. Jeremy will give me succinct pieces of advice that I’m like, “Okay, that’s right to the fucking dome. That’s it.” He’s got older brother energy, but he’s younger than me. He was born a dad, I don’t know. He would like that. He has a tape measure he brings to the hardware store, so, you know.

Thomas, because he’s from Guam, partially, but also he was a special and unique person for Guam, to the point where he had to leave Guam – he was the only kid listening to Dinosaur Jr. in Guam. [laughs] Thomas is probably the most unique person I’ve ever met in my entire life. He’s so specific, and he has a great perspective on things I can’t find anywhere else in anybody. If Thomas is out of the picture – God forbid, knock on wood, hope he doesn’t die – I’ll never find anyone like him again, and that’s true. I’d never be able to write songs with somebody the same way. That’s good – that’s a good thing. Also, dude, he’s such a natural musician. It’s crazy. He’s so good at guitar, it’s annoying. It’s stupid. When we’re playing shows, he’ll play a solo or something, and everyone moves to his side of the stage. I’m like, “I’m right here, what the hell?”

Aidan is our newest member and has totally changed the dynamic. We’ve known Aidan just as long, it couldn’t have been anyone else. Aidan’s cerebral, floating around like a woodland fairy everywhere, touched by the world. Aidan does a hundred thousand things and doesn’t talk about it. Aidan just made up a role-playing card game and got it published, and we didn’t even know they were doing it. Aidan’s amazing and a great writer.

My favorite thing about me is I have great hair. That’s it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Star 99’s Gaman is out now via Lauren Records.