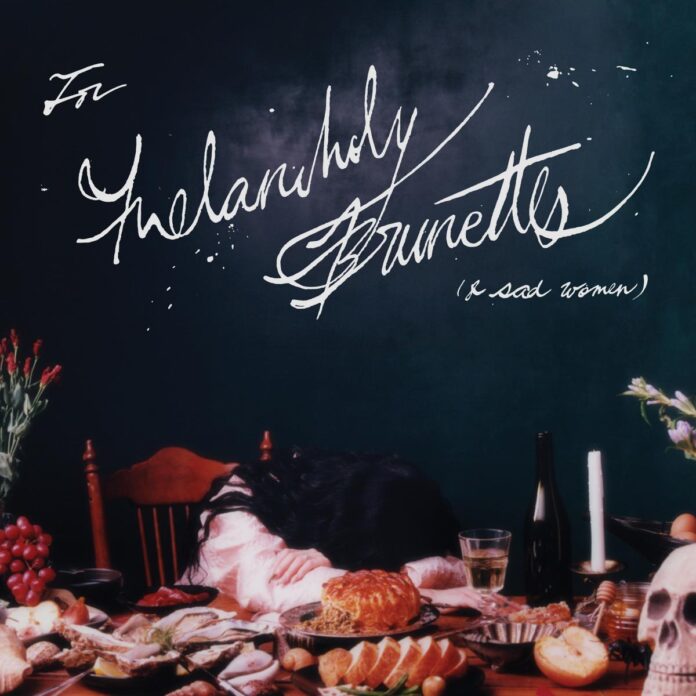

Don’t let the title – itself a nod to a John Cheever short story – fool you: the deeper you listen to For Melancholy Brunettes (& sad women), the harder it is to pigeonhole it. It’s less for any kind of female archetype than it is about a certain brand of foolish masculinity it frames as both timeless and contemporary. It’s about Michelle Zauner, too, a singer-songwriter and author who, following the pop-inflected glee and success of Jubilee, her 2021 breakthrough as Japanese Breakfast – not to mention her similarly lauded memoir, Crying in H Mart – felt the need to shuffle through a cast of fictional characters variously removed and reflective of her own pensiveness. Her nuanced, moody vignettes are matched by richly baroque and luscious production courtesy of Blake Mills, who lends mountainous resonance even to the subtlest songs. “I run my guts back through the spoke again/ Measure by measure, in time with the songs we love,” she sings on the opening track. And For Melancholy Brunettes, like the sadness it evokes, is at the very least a lovely way to keep time.

1. Here Is Someone

The album’s opener springs not from a place of deep imagination or fiction but a very explicit fear: Michelle Zauner is “quietly dreaming of slower days” – which have since materialised during her year-long stay in Korea – but worries about leaving her band behind for so long. She lets the anxiety breathe through an array of instruments – including celeste, sarod, 12-string guitar, gamelan, saxophone, and mandolin – which not only introduce the record’s luscious atmosphere but begin shaping a very particular sadness, not a common or diluted kind. “Life is sad but here is someone,” she sings, trailing off ambiguously at the thought. Or as if to say: but here’s what we can make of it.

2. Orlando in Love

Unless you relate to the specific expectations of being borne an ideal woman, and want to assume Zauner is, too, it’s safe to read ‘Orlando in Love’ as a subtle shift towards the more overtly fictional world of For Melancholy Brunettes (& sad women). Anyone quick to judge the album’s title as being on-the-nose should listen to it in the context of the lead single, which peeks into the seaside life of Renaissance poet Matteo Maria Boiardo, writing 69 (wink wink) cantos for the titular subjects. He falls prey to a siren singing his name, which explains why the otherwise lilting track doesn’t explode quite in the same way that, say, ‘Paprika’ did. The morbid sadness of excessive desire, of quietly dying for an unearthly call.

3. Honey Water

Far from syrupy sweet, ‘Honey Water’ is sturdy and confrontational, an imposing way to turn the dial up while furthering the theme of the previous song. Here, a man’s uncontained lust isn’t part of a distant or mythologized past but brought down to earth, pounding close like Matt Chamberlain’s drums. It’s hard not to hear the echo of Zauner’s euphoric plea from ‘Be Sweet’, to “believe in something,” turned dark and questioning: “Why can’t you be faithful?” As her language becomes flowery – “In rapturous sweet temptation you wade in past the edge and sink in/ Insatiable for a nectar drinking til your heart expires” – the expansive wall of sound does it justice. It’s the longest song on the album, with Blake Mills layering acoustic, electric, and fretless guitar on top of Zauner’s soloing, each bend leaving an emotional sting that cuts through every “I don’t mind.”

4. Mega Circuit

Propelled by Jim Keltner’s thundering drums, ‘Mega Circuit’ weaves the subtle pleasures of the first two tracks with the weight of ‘Honey Water’. More than anything, though, it serves as a showcase for Zauner’s writing, which is at its most caustic and refined, ending with: “Deep in the soft hearts of young boys so pissed off and jaded/ Carrying dull prayers of old men singing holier truths.” MJ Lenderman might just call them jerks, but this speaks louder to the fragile – not just the toxic – nature of inceldom.

5. Little Girl

Allow me to further the comparison – for MJ Lenderman, it’s “the quiet hiss of a midnight piss;” for Zauner, it’s “pissing in the corner of a hotel suite.” She’s taking on the perspective of a distant father “dreaming of a daughter who won’t speak to me,” so distant that he then switches “me” for “her father.” It’s fragility melting into vulnerability, a tragic story so common it may or may not conjure empathy, but the song is gut-wrenching nonetheless. Launer’s lyricism is matched by the sensitivity of Mills’ production – just listen to the synth that seeps through the aforementioned line. A perfect song for imperfect men.

6. Leda

We’re seemingly back in mythological terrain: ‘Leda’ is named after the Spartan queen who was famously seduced and abused by Zeus when he was in the form of a swan. The story reverberates symbolically through the track, which actually feels like one of the most interpersonal on the album. “Oh, you always take it way too far/ Is it the bottle or blood? I can’t relate to you at all,” Zauner sings. The you could be any foolish male figure on the album, but feels especially apt after ‘Little Girl’.

7. Picture Window

When real fear creeps through Zauner’s fanciful songwriting, it seems to turn personal – like ‘Here Is Someone’, ‘Picture Window’ is another one of those songs. But “the anticipatory grief” of the former, as Zauner described it in a recent interview, isn’t quite equal to the one that pervades this song: “Are you not afraid of every waking minute that your life could pass you by?” Her tone isn’t accusatory so much as gently illuminating, the soft stretch of the final word an opportunity to charge forward. “All of my ghosts are real,” she admits, but the ghosts are her home, and the proof’s in the music.

8. Men in Bars

Michelle Zauner and Jeff Bridges’s voices may make for an odd pairing, but it’s startling to hear a male voice this late into an album revolving around toxic masculinity. Rather than fostering some kind of resolution, the song, which bravely reimagines a track by Zauner’s pandemic side project Bumper, only amplifies (and humanizes) the ambivalence, especially since Bridges’ weathered voice strains to reach its upper register – just like the character struggles for reconnection.

9. Winter in LA

More than turning the gaze inward (“I wish you had a happier woman/ One that could leave the house”), the album’s penultimate track is also the one song where Zauner really luxuriates in the titular melancholy. Over breezy, pastoral production, Lauren Baba and Karl McComas-Reichl’s strings trace a particular shade of yearning: wanting to be the kind of woman who loves the sun, though Zauner’s textured melody alone says it all. She may not be writing “the sweetest songs” for the man she loves, but there’s an enchanting sweetness in them, no doubt.

10. Magic Mountain

On one level, ‘Magic Mountain’ finds Zauner embodying Hans Castorp, the hapless young man in Thomas Mann’s novel of the same name who becomes stuck in a tuberculosis sanatorium. But the mountain is also Zauner’s artistic pursuit, and the “new man” he vows to return as is, well, the artist – or the woman. The song considers any kind of pause – like the period of relative idleness in which Zauner wrote parts of the album – as a catalyst for growth. “Bury me beside you,” she sings finally, “In the shadow of my mountain.” The you, this time, is genderless and unbound; the mountain is for everyone.