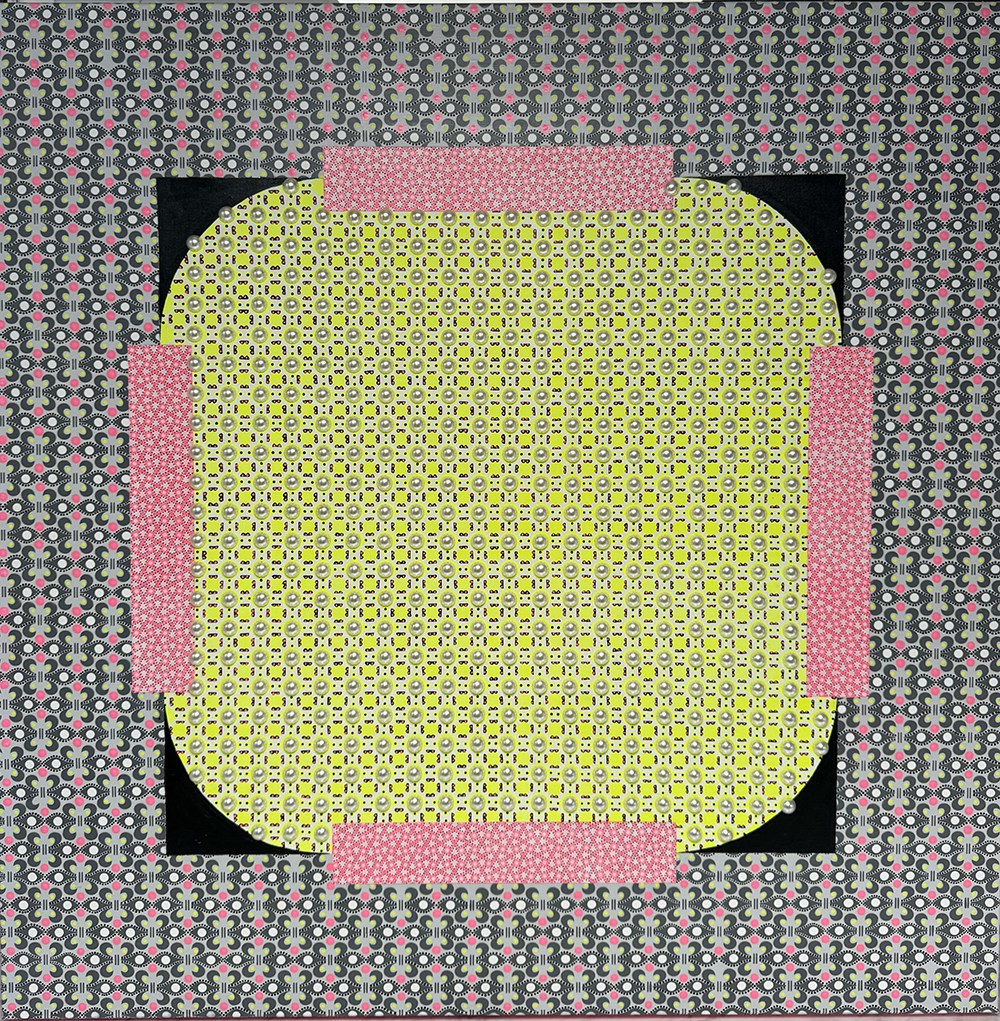

When you first approach Wild Afternoon, your eye is really drawn to that square of electric chartreuse bursting through the center of the canvas. Its corners are softly rounded, as if the shape itself is gently breathing. Even before you notice the tiny matrix of charcoal marks and dots stamped across its surface, or the glint of faux pearls at each intersection, it seems that hue alone stops you in your tracks. From there, Zhou’s layers unfold — a strangely mesmerizing visual ritual that pulses with tension between freedom and restraint.

Surrounding that vivid green block is a field of repeating motifs, a lattice of dark-gray forms set against a slightly lighter gray. At each junction a fuchsia dot appears, brightening what might otherwise feel drab. From a distance it reads like wallpaper or tiling; up close you see each pattern was hand-painted, edges wavering ever so slightly as the artist’s brush repeats its moves. This matrix feels less decorative than mechanical — a kind of cage of shapes. It kinda reminds me of city streets, cubicles, even the gears of a really fast routine. Against it, the neon square throbs like a heartbeat trapped in circuitry, alive and insistent.

Embedded across the green plane are dozens of small, pearly beads. They sparkle softly, each catching light where texture meets surprise. Here, pearls aren’t just fancy — they’re tiny protests — little affirmations of self against the flattening force of the pattern and gray. Each pearl silently says I matter. Together they form a constellation of private moments, small interruptions in the daily hum, and it’s almost enough to rearrange your internal organs with the tension it builds.

At the midpoints of each side sit four bands painted coral pink. They look like strips of tape or plasters laid over wounds. Up close you notice the pink fractures into micro-diamonds at the edges, which really reminds you these bars are fragile. Yet their symmetry — north, south, east, west — gives them weight: defensive, even architectural. One strip hints at marginalization by floating at the edges, never quite bridging the gap. Another suggests exploitation in turning a “feminine” hue into a barrier. Powerlessness shows in their fixed positions — immovable fixtures in a rigid frame. Cultural imperialism seeps through in the faux texture, maybe reminding us of narratives written over personal identity. The pink bands press in as if sealing the neon shape inside, making you feel every push and pull.

Run your hand — metaphorically — across the painting and you feel ridges and valleys. The background’s dull sheen contrasts with the smoothness of the green field, while the pink bars carry a matte, chalky presence. In places, the paint builds up like compacted sediment. Scratches cut through layers, like cracks in memory. Thick peaks catch light and throw tiny shadows. In this landscape, you almost trace the artist’s process — brush to canvas, hand to material, thought to gesture. It’s painting as excavation. Each decision records a moment of making, an impulse, a hesitation. The work doesn’t hide its labor. Instead it honors the endurance needed to persist — to paint, to think, to live — under conditions that can really grind you down.

Wild Afternoon first showed at the Shanghai Young Artists Exhibition in 2024, its neon light cutting through the frost-white halls of Huacui Art Center. There it felt like a fast jolt of color in a sea of pale walls. In Düsseldorf’s 16art8 Gallery, part of Fragmented Wholeness (2025), it entered a European conversation about space and identity. And most recently it settled into Montreal’s 1215 Gallery, inviting North American audiences to think about how visual—and social—systems shape our daily moves. In each city the work’s journey echoed Zhou’s own path — born in China, trained in Scotland, now speaking to viewers across continents. The green square reads like a passport stamped “other,” while the surrounding framework gestures at systems that map and categorize. This trajectory underscores themes of displacement, confinement, and endurance — showing that travel brings both freedom and friction.

Shapes arrest our gaze because they feel familiar — wallpaper, fabric prints, floor tiles. Zhou draws on that shared visual language only to knock it off balance. The background pattern kind of resembles a chorus of watchful eyes, uncanny in its recognition, like recalling a childhood room or a corporate lobby. But that familiarity fractures with each pink dot — ornament becomes obstacle; motif becomes protocol. And that shift makes you ask: where in your life are you stuck in a matrix? How do familiar designs lock you in?

Though never preachy, Wild Afternoon hums with political energy. The green form seems to breathe under siege. Its warmth challenges the cool precision of pattern. But the confinement is real. The four pink bars constrict, the pearls punctuate, the scratches scar. In this small battlefield of color and shape, Zhou maps a universal struggle: the will to speak, to move, to exist fully in a world that categorizes and silences.

Zhou’s title — Wild Afternoon — invites you to see the everyday as ritual. Afternoon suggests a routine tea break, a lull in the day, predictable light. Yet she makes that time wild — untamed, awake. The painting itself is a ritual of defiance. To make it, Zhou returned again and again to her canvas, layering, inscribing, disrupting. To view it is to join that ritual, to take part in its persistence.

In our rush for big gestures, we often overlook the small. But Zhou’s work insists care comes in tiny pearls, in plasters pressed to a wound, in motifs softly upended. She shows freedom isn’t a single roar but many murmurs. The beauty here isn’t effortless but built, brick by brick. Each micro-mark, each scratch, each bead is proof of time spent drawing, thinking, resisting.

Wild Afternoon doesn’t promise tidy endings. That neon square stays pressed against bars. The matrix holds firm. But in the glimmer of pearls and that almost radioactive hue, you glimpse possibility. The painting doesn’t shout — it whispers. It asks you to slow down, to notice the tension between shape and structure, between decoration and constraint. It reminds you that even in the stiffest frameworks there’s room for persistence, for surprise, for your own restless figure to wriggle free.

Standing before Jing Zhou’s Wild Afternoon, you feel the weight of systems, the pulse of memory, and the tremor of small rebellions. You realize painting itself is a practice of care and endurance. In that sense, Wild Afternoon is more than art — it’s a living ritual, an invitation to see how color and shape reclaim space for the self.