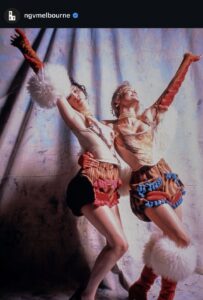

Put Vivienne Westwood’s punk anarchy stitches in the same room as Rei Kawakubo’s avant-garde brain-melting silhouettes and you get a fashion match where the only loser is the one who didn’t book the NGV ticket. It’s everyone’s favorite fashion talk right now, with editors flying across hemispheres, stylists losing all structural integrity and every fashion student pretending they’ve “always been deeply influenced by both designers”.

Punk Fashion as a Cultural Weapon: Westwood’s Manifesto

Vivienne Westwood’s collections never aimed for “proper”. Corsets felt like historical glitches and tartans never really played nice with tradition. Her work with McLaren turned the King’s Road into a political stage where ripped tees, safety pins, and bondage trousers became middle fingers to the British keep-it-polite culture. She claimed them, stamped them with her signature, and dragged them onto runways and the mainstream with the very loud message that fashion is, in fact, a form of cultural protest. In other words, Westwood is a major reason Punk and New Wave didn’t die in dimly lit London basements. If environmental activism became PR-friendly, fabric became a weapon for questioning authority, and subcultures never went back underground, it’s partly because Westwood made it all wearable, bless her, honestly.

What Even Is A Garment? Kawakubo’s Conceptualism

Rei Kawakubo has always worked in her own dimension, she didn’t really care about wearability either, she was too busy reshaping the idea of the body itself. Her silhouettes at Comme des Garçons turned clothing into something you had to take a moment to think about, practically causing fashion moral panic more often than you’d think. In her retail world, Dover Street Market, fashion is part gallery and part experience, a space that constantly reminds us of her fingerprints all over the industry, from messing with proportions, to all-black 80s shockers, to Yohji Yamamoto dialogues. Now, if avant-garde became everyday vocabulary and sculptural fashion found its way into museums, it’s largely because Kawakubo made the weird, the abstract, and the “is this even clothing?” a conversation in your favorite label’s table.

Why It Actually Makes Sense To Share A Room

Few know it, but these two have a history of rubbing shoulders creatively. In 2002, they joined forces for a short-lived collaborative collection where Kawakubo cherry-picked Westwood archives and dressed them in Comme fabrics. Honestly, I’m surprised it took this long for them to share a room, they kind of make perfect sense. They use different languages, for sure, but both have spent decades rejecting rules and questioning beauty. Westwood’s anarchy and Kawakubo’s abstraction might look worlds apart, but all I’m seeing is two designers who have been quietly rewriting the same rulebook from very different corners of the industry’s map.