The through-line of Peiyan Zou’s practice is neither material nor a typology but a way of seeing a computational gaze that treats LiDAR not as a survey instrument but as a cultural medium. Across city landscape, architecture, interiors, and time-based art, Zou turns point clouds into arguments about perception: how measurement becomes image, how error becomes form, and how machine vision can widen the moral and imaginative range of creation. A London based artist designer and researcher, he has been recognised with the RIBA Donaldson Medal, the Bartlett Medal, and the Fitzroy Robinson Drawing Prize. He works at the seam between technical exactitude and poetic disturbance.

Zou says: “I try to use LiDAR’s so called ‘errors’ rather than fix them. The variety in my practice from objects, interiors, and architecture comes from one aim: exploring a more universal, future adaptable method of creation, where machine vision is part of the toolkit.”

Architecture: From “As-Sensed” to “As-Built”

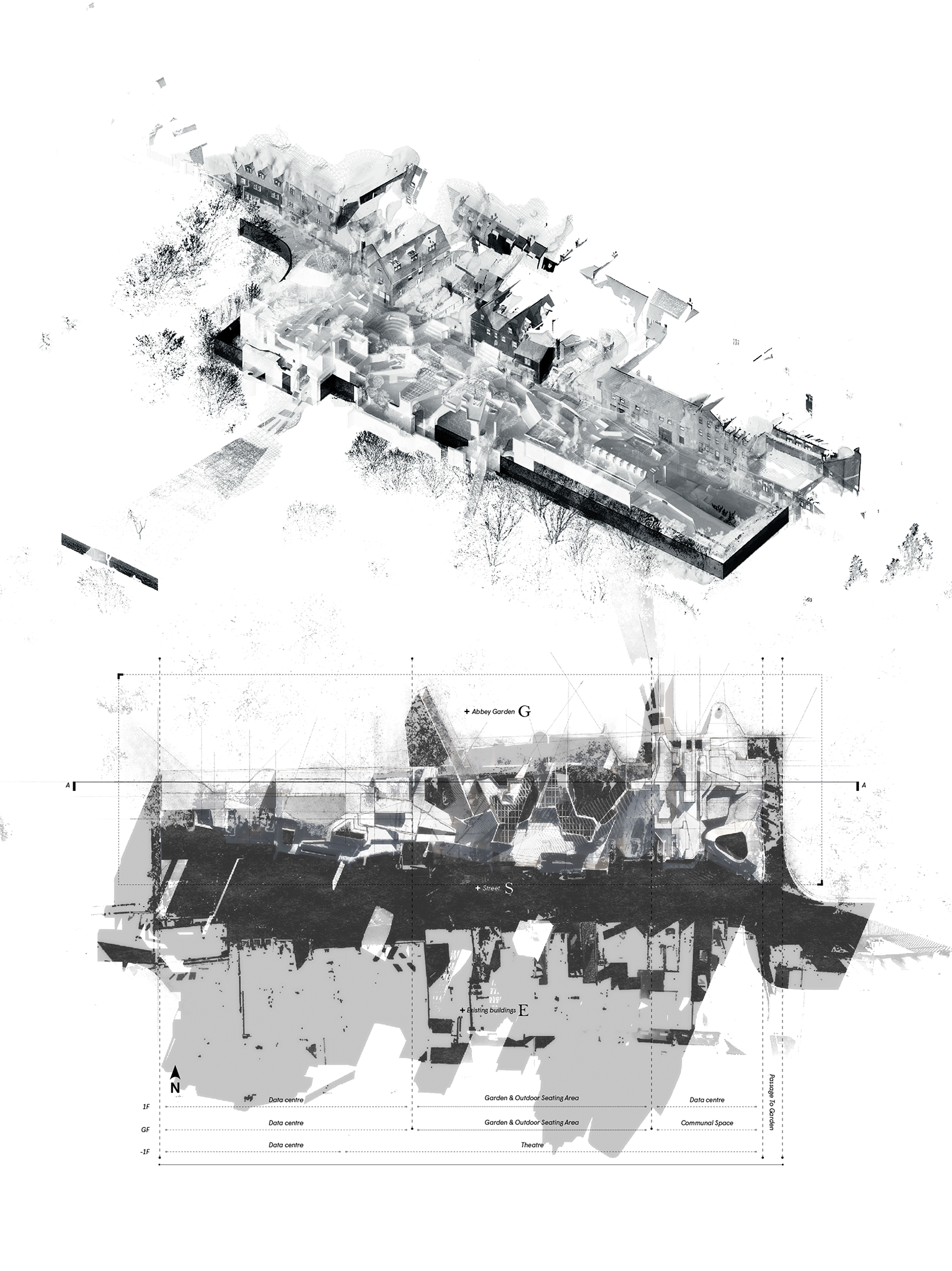

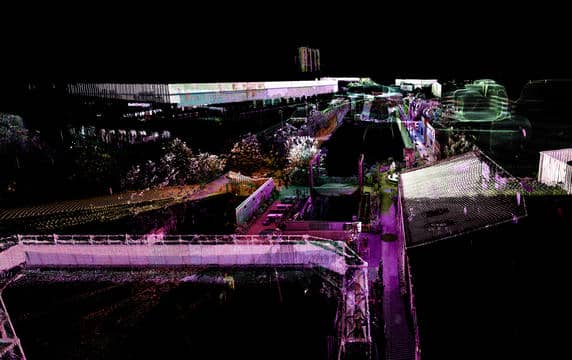

Zou’s LiDAR driven research into architectural and urban perception follows a clear arc. It begins with early student projects, moves through the AIA New York hosted PlanScapeArch Conference 2024 keynoted by Iain Macdonald, and extends into the context of the 2025 Venice Biennale. Here, LiDAR is recast not as a street “capture” device but as a medium for expressing urban uncertainty: occlusion, motion blur, and spectral drift, the very phenomena that conventional pipelines try to erase. Rather than sanitise them, Zou keeps and activates these traits, letting confidence scores and imaging artefacts drive sensing and volumetric reconstruction. The result is an as sensed urbanism that treats noise as civic information, not computational waste.

In Peter Cook’s studio, most visibly on the Serpentine × LEGO 2025 project and under NDA on Saudi commissions, Zou has been the quiet engine behind customised parametric toolsets. As Architectural Designer, he turns concepts into actionable geometry and feeds the results back into the design loop, working at the boundary between workflow and authorship.

Recently he has extended this method to the digital twinning of Sir Peter Cook’s drawings. These are not simple copies but dynamic and interactive counterparts. In collaboration with Norwich University of the Arts on the Peter Cook Wonder Hub, Peiyan contributed to the interior exhibition design and integrated these twins into the spatial narrative. The result preserves the temperament of the originals while opening new modes of interpretation, including animated presentations, VR experiences, and live 3D models generated from 2D drawings. This work lays a clear pathway from pieces on the studio wall to a responsive computational platform.

Interiors: Performance as a Material

As Director and co-founder of Wedge, Zou translates scanning logics into inhabitable façade details and interior objects. He has built a generative toolkit in which LiDAR-based sampling seeds the form and surface behavior of furniture and cladding—a future-facing spatial experiment developed with Chinese manufacturers and labs rather than a parametric “style.” The medium is silica sand, 3D-printed with a biodegradable resin binder; the material can be disassembled and reused up to eight cycles.

“Imagine a chair at home,” he notes. “Two years later you return it to Wedge. We mill and sieve it, reload the sand, and reprint a table. Furniture stops being a fixed object and becomes geometry that adapts to need.”

This proposition is already in production. Wedge has launched market-ready pieces at 3daysofdesign in Copenhagen, at London Design Festival, and at Material Matters, and has delivered what is billed as the first mass-produced, silica-sand-printed furniture for a Swiss hotel client. ELLE Decoration UK recognised the strength of this approach and selected Wedge for an exclusive feature during London Design Festival, the only exhibitor to receive this distinction and to represent Material Matters. The studio is now scaling into more spatial commissions, including landscape components for a new project in Denmark and an experimental dining environment for a noted restaurant, with Zou treating Wedge as a multi-scalar playground. The stakes are clear: this reframes computation from prototyping myth to supply-chain reality, tying algorithmic authorship to durability, sustainability, and novel materials, while testing a bold commercial pathway for his machine-vision design methodology.

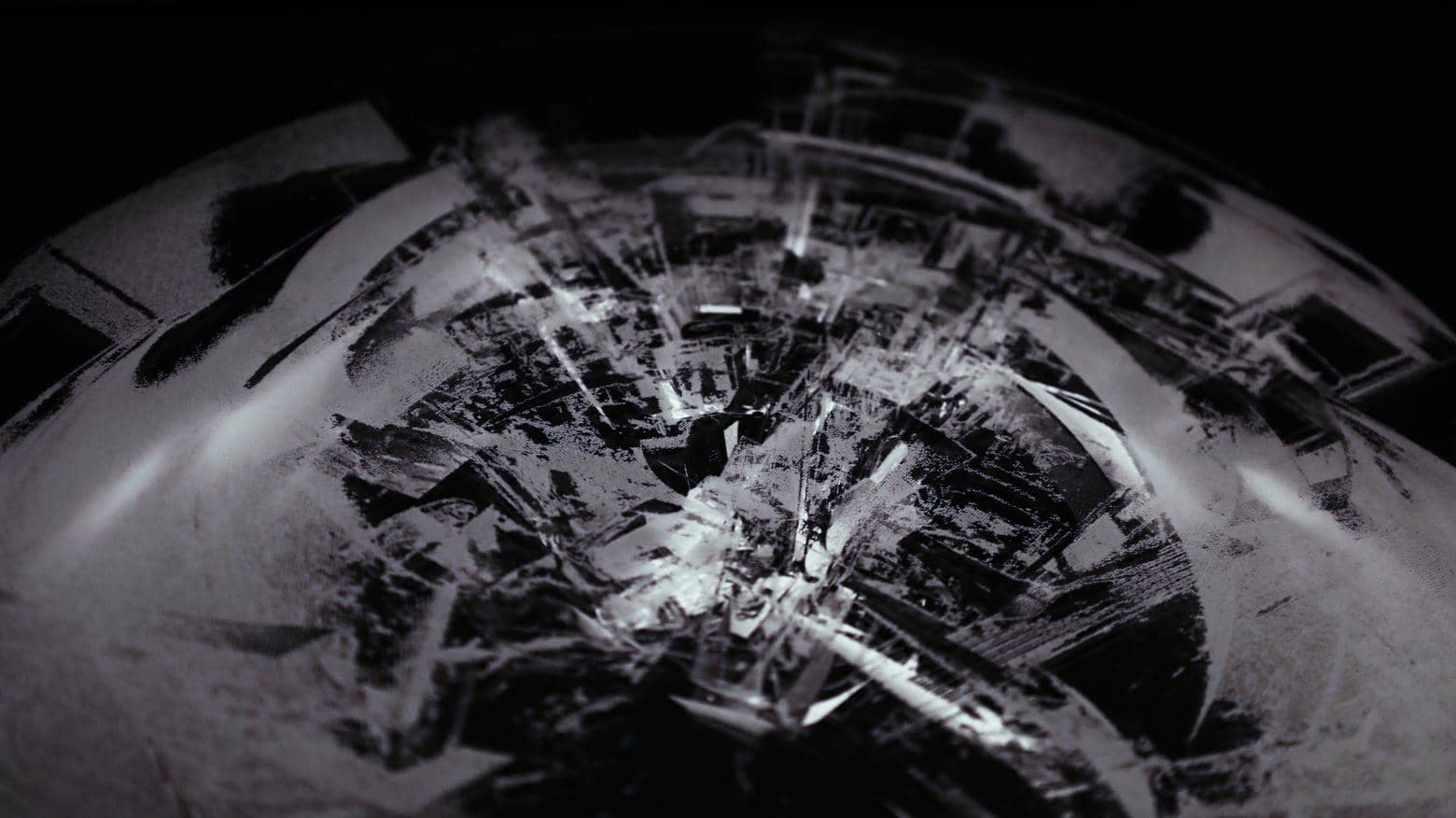

Art: The Ethics of Error

Zou’s artistic practice orbits the ethical dimension of machine vision. From the Peckham Rye Old Waiting Room to galleries in Hackney, he treats LiDAR point clouds as paint, as a photographic medium, and as a sculptural substrate. The data can be layered, abraded, and made to flow. His visual language of fracture, erosion, and apparition grows from a refusal to “correct” the scan. Errors are not edited out; they are inscribed as structure, implicating the viewer. If the machine looks for us, what do we still ask of the image? Moving between design and art contexts, the work declares a hybrid grammar that is both proposition and tool, much as painters once used the camera obscura to pursue realism.

“This isn’t a side project that wandered in from my architectural journey,” Zou notes. “My education at The Bartlett School of Architecture taught me to think about architecture from non-architectural angles. “I value not only the novelty of this method but its rigour. It is a way of working in which drawing, making, research, and experimenting strengthen one another.” Seen across venues, exhibitions, and collaborations, a clear picture comes into focus: an artist designer using advanced technologies to explore how we see and feel space, pointing toward futures that may be more posthuman in how they sense the world.

A Grammar of “Constructive Uncertainty”

What distinguishes Zou’s practice is his refusal to police the boundary between tool and medium. In architecture, LiDAR unsettles the authority of spatial measurement. In interiors, it choreographs encounters between the body and recyclable materials. In art, it stands in for the camera obscura’s pinhole and exposes our appetite for augmented vision. For him, technology is a grammar whose language shifts with context. That portability keeps the work singular without slipping into techno kitsch. His computational instruments—sampling, voxelisation, and error field transforms—stay legible whether scripting a façade, shaping a seat, or composing scan-based photographs.

The risks are real. Without a careful ethics of selection—what to keep and what to erase—the poetics of the artefact can slide into mannerism. Zou’s strongest works confront this directly and bind aesthetics to responsibility. Is a city sensed, and if so, by whom, under what conditions, and to what ends. When these questions are made explicit, the work’s beauty hardens into critique.

Toward a Civic Computation

Peiyan Zou’s contribution is to reposition frontier technologies as civic instruments: tools that do not simply optimise workflows but reorganise how we attend to the world. He insists that computation carries a responsibility to perception, and his projects model a practice in which architecture, interior design, and art serve as three theatres for the same argument. When treated with care, uncertainty isn’t a flaw in our tools. It is part of the world we share. In this spirit, Zou’s LiDAR aesthetic is less about ever finer scans and more about a truer way of living in and with places.