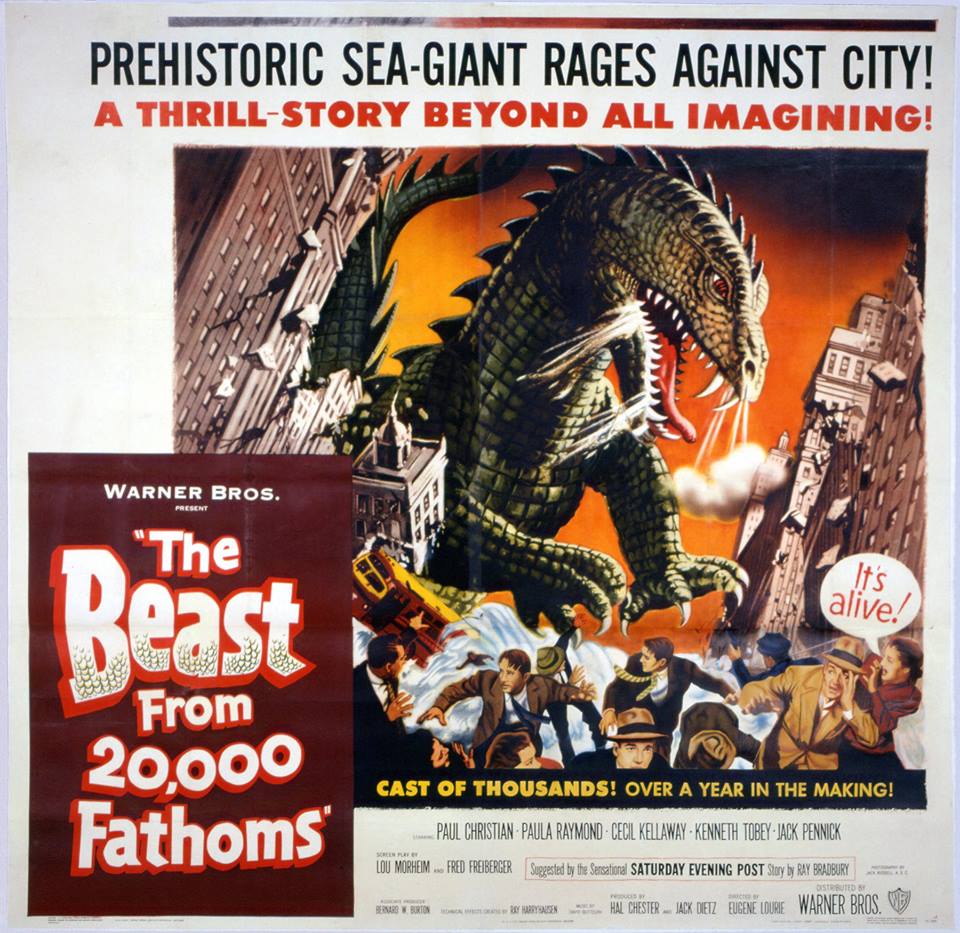

‘A Rhedosaurus is brought to life by an atomic bomb test in the Arctic. Bewildered and disorientated, the creature makes its way to its original prehistoric home, which over the millennia had become New York City.’ – from Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms is arguably one of the best American science-fiction films of the 1950s. With dazzling special effects courtesy of Ray Harryhausen, a fabulous score by David Buttolph, and some excellent camera work, The Beast is an iconic part of the monster sub-genre. Despite some questionable narrative elements, The Beast is one of the most stylish of its kind, earning respect and a dignified place in cinema history.

The narrative of The Beast is perhaps simple and predictable; a giant monster is awoken by a nuclear test to wreak havoc on the modern world. However, such an assessment is one made with a modern understanding of genre tropes and formulas. Few films, bar perhaps King Kong in 1933, had depicted such a spectacular story. The regular narrative beats of the monster sub-genre found in films that were to follow owe a great deal to the success of The Beast, which despite its measly $150,000 budget, grossed over $5 million for Warner Brothers in June 1953.

However, the writing of The Beast is not entirely without fault either. One would assume that the simplicity of the story would have allowed for greater emphasis on the character dynamics to guide the narrative and provide dramatic tension. To an extent, this is achieved (there is a peppering of romantic tension between Paul Hubschmid’s Tom Nesbitt and Paula Raymond’s Lee Hunter), but a certain similar film from November 1954 demonstrates how much can be added to a relatively simple story through character. Without turning this review into a comparative essay between The Beast and Ishiro Honda’s gripping Godzilla, it must be noted that the characters in The Beast, whilst charismatic and engaging, don’t match the same level of nuance and depth as those in Honda’s nuclear nightmare. Indeed, the emotional range of the characters in The Beast rarely extends beyond mild surprise, scientific confidence, or self-assuredness.

Perhaps the weakest point of The Beast’s narrative however lies not in its characters but in how it ends. Whilst the sight of the raging Rhedosaurus writhing around in the flames of a burning Coney Island rollercoaster makes for one of the film’s strongest visuals, the writing behind it is unsatisfying. Having the creature killed through the use of a radioactive isotope arguably mitigates the cautionary nature of the film. Nuclear weapons may have unleashed mighty horrors, but the atom is apparently sufficient to kill those horrors as well. Such an end to the mighty beast is emblematic of a contemporary ‘trust’ in the bomb; one that is juxtaposed to the terror of the bomb in a film where its use is presented as producing a literal monster. Perhaps such a tale works to the extent that it assuages fears that the bomb is unstoppable – that this atomic phantom can be swept away. On the other hand, there are arguably less clumsy ways of writing for such an effect.

Despite its arguable story and character shortcomings, the design work for The Beast is tremendous. The New York location photography and surprisingly lavish costume design (surprising considering the small budget) give the film a stylish air. To say Paula Raymond’s long sheepskin pea coat is elegant is something of an understatement. Perhaps the appreciation for such aspects comes from a retrospective delight at 1950s aesthetics, though this has certainly allowed the film to age gracefully. The camera work during the Rhedosaurus’ rampage in the Big Apple is breathtaking, with high-angle dolly shots gliding along with crowds of fleeing civilians. John L. Russell’s cinematography elevates the monster’s attack into a frenzied panic, perfectly immersing one into a city besieged by a leviathan.

Underpinning such gripping visuals is David Buttolph’s striking musical score. The Rhedosaurus’ main theme is striking, yet graceful. As the notes of the theme descend, so too does any hope of defeating the Beast. Buttolph’s Beast theme is also effectively used throughout the film, making one aware of the Rhedosaurus’ presence without it being shown. Following Dr. Elson’s death, the sad strings that underpin the tragedy end with the descending notes of the beast’s theme; his death subtly linked with the prehistoric menace. From the shocking brass that plays behind the Warner Brothers logo, Buttolph’s soundtrack is a joy to be heard and is one of the film’s strongest qualities.

Of course, one cannot speak of The Beast’s qualities without respect paid to special effects pioneer Ray Harryhausen. Certainly, the Rhedosaurus is an arresting sight to behold. The Rhedosaurus’ walk through New York is convincing and stunning. Through meticulous stop-motion animation, Harryhausen imbued the Rhedosaurus with a heart and soul. This beast is not a mindless monster as with other creatures of the era. The Rhedosaurus, as Ray himself pointed out, is ‘a poor lost soul’, awakening to a time that has forgotten it and trapped it to isolation. What the film may lack in genuine character depth, it makes up for with genuine pathos in the beast itself. A testament to Ray’s character realisation is that never do any of the characters in the film look upon the Rhedosaurus with open sympathy. On the contrary, one’s decision to look upon the beast with sympathy is a decision made because of its characterisation – a quality realised by Harryhausen. One sees a creature lost and scared, and one feels for it. Without Harryhausen, such a rich engagement with the beast may not have been possible.

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms is a film that has a great deal to offer. Despite its shortcomings with its simple story and basic character dynamics, the film is elevated to brilliance through its camera work, production design, rousing musical score, and masterful effects work. Having aged gracefully, The Beast remains a powerful, and often frightening, look into the atomic age and the horrors that plagued the minds of those who lived through it.