The Zone of Interest by Jonathan Glazer

I’m drawn towards films that depict the humanity (simulated or otherwise) amongst the most morally depraved. Historically, even the most vile and selfish specimens of this species are cloaked in some shred of contradiction, whether sincere or constructed as deflection. My interest isn’t a question of empathy. Rather, it’s about emotional accuracy. No film has a didactic imperative, but actually recognizing “evil” means reckoning with how it postures itself as the opposite: as something tame, respectable, or even pretty. This is the core of English filmmaker Jonathan Glazer’s latest film The Zone of Interest, an experimental representation of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss and his family’s placid domestic life, a single barrier separating their estate and Höss’ deathcamp. Composed mostly of static long shots and little narrative, the film reveals a compartmentalized existence, where delicate images conceal the absolute barbarity just beyond their homelife.

As a quintessence of unfathomable amorality, The Holocaust has received countless artistic treatments to the point where most are banal retreads. Perhaps the most famous visual representation is Schindler’s List. Spielberg’s film prioritizes moral legibility; Amon Göth’s wickedness and Oskar Schindler’s purity are painted with absolute clarity. Things like good, evil, and atrocity are all depictable within Spielberg’s composition and contained within the edges of the frame. He is foremost a melodramist. Zone is the anti-Schindler’s List and Glazer the anti-Spielberg. Zone falls in lineage with Claude Lanzmann, the Jewish filmmaker and writer who posited mass genocide, performed as pragmatically as the Nazis did, cannot (and should not) be visualized in archives nor recreation. Glazer makes no efforts to represent the unrepresentable. He’s less interested in making a statement about the inconceivable violence of Nazism and, instead, about how images can fashion genocides as innocuous. This is, of course, a crucial part of depicting Nazism, since its violence was so consciously tied with aesthetic self-presentation.

Zone is about aesthetics and how controlled images mask violence. Strolls through a lush garden are soundtracked by faint, droning rumbles of the Nazi death machine. Compositionally peaceful moments are pierced by a harrowing cry in the distance. Despite the schematic filmmaking, Zone doesn’t perpetuate Nazi aesthetic ideals. Something always lurks in the distance, off-setting everything. Glazer upsets the formal uniformity with nightvision scenes, a fade into an all-consuming red, and Mica Levi’s howling overture and coda accompaniment, conducted over a black screen. These moments destabilize the Höss’s family’s imagined reality, incorporating a violence which can no longer be hidden. Zone isn’t split between idyllic images and abject sounds. Sound and image fuse; neither exists in a vacuum. It’s about the façade of images and our obligation to question them, to see beyond tranquil country homes, opulent architecture, and children running carefree in the yard.

I have my hesitations about the film’s overall effectiveness. A final-act geographical relocation and narrative beat betrays the movie’s austerity. I couldn’t help wonder if Glazer’s artistry might be better suited as an installation piece. There’s also one question I can’t shake. This isn’t a film about Höss or his family, it stays external to their subjectivities. Even dialogue is incidental, mixed-down and overpowered by ambient sound. But it’s also not a film about the nameless and faceless victims of judeocide: anonymous and invisible lives pushed outside the movie’s parameters, excluding the occasional marker of death Höss cannot wall-up or sweep under the rug. And so: if the film is more interested in the broad overarching relationship between fascism and aesthetics, why ground it in the context of a specific genocide? While Glazer’s better suited to the high-concept surrealism of movies like Under the Skin, Zone is full of powerful provocations. Regardless of whether the film entirely “works,” it sparks invaluable reflections on the limits of aesthetics. [3.5/5]

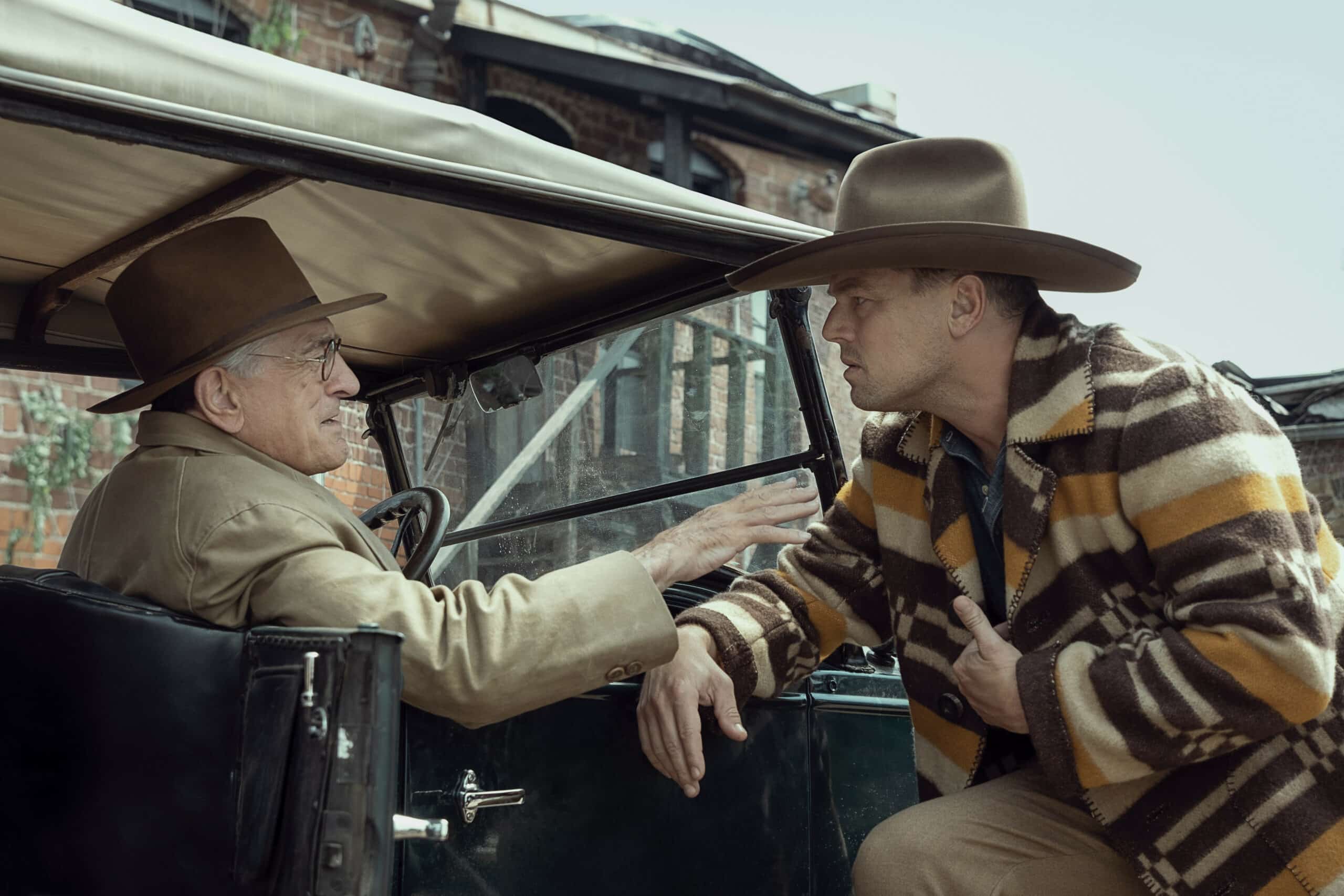

Killers of the Flower Moon by Martin Scorsese

On the heels of a late-period hot streak, Martin Scorsese returns with a colossal western-epic. A true story, the film depicts a 1920s genocidal scheme wherein wealth-hungry white settlers massacred oil-rich members of the Osage tribe. Based on the non-fiction bestseller of the same name, Scorsese restructures David Grann’s source material, de-emphasizing the FBI perspective and erasing any glimmer of a white savior narrative. Instead, he focuses on the perpetrators: byproducts of white supremacist capitalism. Scorsese’s crime films often center otherwise unremarkable figures woven into a mass criminal enterprise. Like Frank Sheeran before him, Ernest Burkhart (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) is a subservient dunce. Lumbering and witless, he’s a spineless sack without principles: maybe the most reprehensible of Scorsese’s many villainous protagonists.

Yet DiCaprio’s performance, soaked in hokey twang, is a miscalculation. He pouts and scrunches his way across the movie, evolving from bumbling awkwardness into comic theatrics. It’s a hammy portrayal, especially opposite Lily Gladston’s restraint. The emotional crux of the movie is their romance: a relationship which feels artificial since their performances belong in different films. DiCaprio’s moments of doubt—a conflicted conscience interrupting his genocidal scheme—hardly resonate when his characterization is otherwise divorced from any spectrum of authentic emotion. It’s the work of an actor keen to upstage his scenemates, always trying to redirect the spotlight onto himself, fearful he’s robbed of magnetism if he goes quiet for a moment. The movie’s emotional climax is a long-take close-up of his visage, fumbling a sequence of facial acrobatics, clearly envisioning it as his Oscar clip at the same time. Whereas DiCaprio’s clowning suits other films (e.g. the vulgar satire of Wolf of Wall Street), it’s misguided here.

A bad DiCaprio performance isn’t enough to stop Scorsese though. Some of Flower Moon’s compositions are breathtaking: a line of men running around a ring of fire obscured through a fogged glass window, a darkly lit tableau of masterfully-blocked criminal conspirators, a spiritual deathbed vision, etc. Scorsese’s filmmaking remains energetic for its three-and-a-half-hour runtime. Yet the storytelling is jarringly familiar. Scorsese applies his signature Goodfellas structure: constant montage, rapid-pacing, tongue-in-cheek cutaways. It’s a mode he’s mastered, but here the form feels dislocated from its content. The tragedy and genocide are sometimes sidelined by the film’s style, drawn foremost to propulsive pacing. Whereas The Irishman makes a final act turn into slow elegy, Flower Moon raises the silly question: can a movie be too entertaining and well-paced for its own good? At its worst, Flower Moon is a retread for the veteran filmmaker. Whereas Scorsese’s last couple films were vivid and disarmingly personal, this sometimes feels more self-imitational than self-confrontational. [3/5]

May December by Todd Haynes

Much of Todd Haynes’ career follows the footsteps of the melodrama masters: Douglas Sirk and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Whereas Haynes’ films oscillate between campy excess (e.g. Poison) and aching tenderness (e.g. Carol), he’s struggled to reach Sirk or Fassbinder’s marriage of irony and sensitivity (prime exception: his Karen Carpenter barbie-doll biopic Superstar). That changes with May December. Haynes’ latest is a cocktail of grotesque diva-psychosis, uproarious irony, pathos, and, amidst the feverish perversity, genuine compassion. It’s a virtuoso juggling act orchestrated by a filmmaker in peak form.

Inspired by the case of Mary Kay Letourneau, the movie follows a middle-aged suburbanite (Julianne Moore in a late-period Bette Davis-style performance) and her two-decades-younger, Korean-American husband. Their relationship, which began when he was thirteen, is founded on statutory rape and grooming: something 90s tabloids sensationalized. Now, with two high school children on the verge of graduation, the predatory origin of their marriage remains an unspoken subject in their white-picket fantasy. However, a method actress (Natalie Portman) enters their domestic circle, researching for a role she’s playing in a cinematic adaptation of their life story. Sprouting from tension between the two women’s exploitative egos, the film unravels as Portman’s character snakes her way through the family’s repression, revealing a festering wound at the core of an American family. With glossy digital images and off-kilter framing, May December plays like a divinely executed Lifetime movie (that’s praise).

If this story sounds harrowing, it is. Immense credit to both Moore and Portman who deliver shamelessly unflattering portrayals of two shark-toothed egos and the collateral damage they wreak. May December fosters a looming sadness as Moore’s husband wrestles with a life lived in subservience to his groomer wife. He’s forced to confront that he’s spent two decades as a glorified fetish object. At one point, he smokes weed with his teenage son: a first try for the thirty-six-year-old man. The scene is quietly tragic. Forced into premature fatherhood by a much older wife, he was robbed of adolescent self-discovery. These moments of gravitas go hand-in-hand with Haynes’ biting irony. The film announces its camp sensibilities in the opening scene, which ends with a sinister piano sting and tight zoom into Moore’s face as she agonizingly declares “I don’t think we’ll have enough hot dogs!” For Haynes, humour isn’t a reduction of anyone’s pain. Rather, it’s the only means of understanding a world this foul. [4/5]

Anatomy of a Fall by Justine Triet

A middle-aged husband falls to his death from the attic window of an isolated mountain home, sparking the central intrigue of Justine Triet’s fourth feature Anatomy of a Fall. Sandra Hüller stars as the widow and prime suspect for the potential homicide. Her entire being is challenged and cross-examined in gruelling legal proceedings, bombarded and dehumanized. The trial extends beyond the purview of her husband’s death, into an invasive weighing of her moral character. Triet studies the minutiae of the French legal system, its prejudices, and its inadequacy in uncovering an objective truth. Ultimately, Anatomy is less preoccupied with answers (it brings few) and, instead, treats truth as a relative term, subject to our own free will. By the end, the film’s lengthy procedural style runs a tad dry. But moments of impressionistic style and Hüller’s morally ambiguous performance pull it to the finish line. Despite its bleak tone, there’s also an unexpectedly hilarious 50 Cent gag thrown in for good measure. [3/5]

Firebrand by Karim Aïnouz

With Mariner of the Mountains, Brazilian filmmaker Karim Aïnouz composed a complex hybrid work: a travelogue, essay film, reflexive documentary, dream journal, and memoir conjoined into one. The movie was graceful and introspective, exploring lost generational roots and dreams of postcolonial futures. On the other hand, Firebrand, his first English-language movie, has the eloquence of a rotting corpse. A work of historical speculation, the film follows Catherine Parr, the sixth wife of notorious uxoricide enthusiast King Henry VIII, as she tiptoes around her monstrous husband, sneakily combatting the repression and religious tyranny of his reign.

Not only does Firebrand lack the presence of Aïnouz’s creativity and precision. It also seems to the lack the presence of any filmmaker steering ship. Though Aïnouz’s name appears in the credits, the movie feels spearheaded by a second-unit director. Every shot looks like coverage nabbed in a frantic scurry: anonymous, flat compositions with no spatial awareness clumsily cut together by a presumably blindfolded editor. It aspires only to competence and falls short of even that. Performances are similarly lifeless. Alicia Vikander stars as Catherine, less a character and more a statue sanded-down of any nuance into a voicebox for liberal feminist rhetoric. Jude Law’s King Henry caricature is a ballooned monstrosity of an ogre, tottering about royal chambers with sadistic intent. He is the least creative imagining of evil, groping and gargling his away across the runtime. The film’s only respite from humdrum catatonia is the occasional splash of body horror: scenes interrupted by sudden purulent eruptions of Henry’s infected (and rapidly spreading) leg wound. Yet sure enough, Firebrand quickly cuts away from its refreshingly grotesque images, lacking the good sense to revel in bad taste. In a festival year replete with three-hour-or-longer movies, no runtime felt more torturous than Firebrand’s two hours. [1/5]

Close Your Eyes by Victor Erice

Victor Erice’s Close Your Eyes is the latest of late-style, the oldest of old man movies. The legendary Spanish filmmaker spins his first feature in thirty years: an intimate epic about a retired filmmaker haunted by the memory of his best friend and ex-leading man who, twenty years prior, vanished into thin air. Once a storyteller of children’s’ subjectives, Erice’s filmmaking now grapples with old age and mortality. He excises the magic realism of his earlier narrative works and strips down to an economy of mostly shot-reverse-shot close-ups. It’s a welcome restraint, exquisitely lit and patiently still. The movie’s first half is a painful personal archeology, rummaging through lost artefacts, paying visit to ghosts of the past. Every character interaction exhumes a deep memory twinged with sorrow. Everyone speaks in subdued hushes, withered by time. The second half is gooier and less piercing. Erice shakes the film’s ambient melancholy for a more concrete emotional palette and central conflict. The last moments are shamelessly sentimental, sculpted from a whole lifespan of nostalgia.

Like almost all Erice films, Close Your Eyes is a movie about movies. Yet here, the self-reflexivity is cruder and burdened by blunt “the miracle of cinema”-type musings. The most egregious moment occurs mid-transit when the protagonist skims a flipbook version of Lumière’s Arrival of a Train: a cliché icon deployed unimaginatively. These moments are minor but stem from a larger issue. In Erice’s past films (i.e., Spirit of the Beehive, El Sud, La Morte Rouge), the dynamic of cinema-history-memory is a gateway into a socio-historic consciousness. In those works, cinema becomes deflection, imbued with Franco-era traumas that cannot be spoken out loud. In Close Your Eyes, cinema’s function is much less rich. It’s represented as a force supplementary to the human being, something that remembers what we can’t and fills the gaps of our own consciousness: an imperfect archive adopted as appendage. This understanding of the medium is moving, but it’s hardly unique from other films, such as Giuseppe Tornatore’s saccharine nostalgia-fest Cinema Paradiso. Still, Erice’s love (for his characters, his medium, his world) is infectious and feels earned because it’s accompanied by such palpable heartache. [4/5]

Man in Black by Wang Bing

Man in Black, Wang Bing’s second film at Cannes this year, is almost antithetical to his other: Youth. While Youth is a comprehensive, fly-on-the-wall plunge into its subjects’ world, Man in Black is a concise portrait piece, hinging on testimony and performance. The subject: Wang Xilin, the eighty-six-year-old composer and survivor of torture and imprisonment during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. For the movie’s duration, he’s completely naked: a statement of the vulnerability he brings to the film. Shot in Paris’ Théâtre des Bouffes, Man in Black’s first half consists of Wang Xilin walking, stretching, performing abstract movement pieces, hollering, or playing piano. These are sporadically paired with the thunderous accompaniment of his own symphonies. In the second half, he sits down and regales his life story. His voice is a soft murmur, almost drowned-out by the soundtrack. Combining his art with his biography, Man in Black strives to capture the essence of Wang Xilin. While admittedly a minor work next to the scope and immersion of Youth, the movie is a keen pairing of a filmmaker and subject, each devoted to openness and sincerity. [3/5]