Brandon Hendrick was born in New York and studied painting at Virginia Commonwealth University before earning his MFA at Glasgow School of Art in 2021. His work has appeared throughout the United States, the UK, Turkey, France, and Bulgaria, and has been included in various publications including Epicenter NYC, Akşam, and beloved The Scotsman. Hendrick’s practice uses non-conventional surfaces to paint on – most notably cigarette packs – transmuting the disposability of the object into a physical tension that prevents the act of disposability. The cigarette pack paintings (which began in Sofia in Bulgaria) have expanded to other locations and most recently in Marnay-sur-Seine, France in a residency. The health warnings that are printed on the sides of the packs remain visible along with the textures and creases of the object itself, revealing guises of questions about value, habit, and memory that literally come into the work itself.

A Rainy Day in Sofia (2025) is painted across the surface of a flattened pack. The folds, creases, and warning label remain visible. A stretch of grey sky sits above a line of trees and a blue roof – their forms reflected on a patch of water below. The work expresses what Hendrick describes as fleeting moments and memories in his artist statement, not entirely descriptive, but suggestive enough to allow the viewer to finish the scene themselves. The cigarette box has a fragile, disposable nature yet retains an enduring landscape, and the tension between those two aspects is at the core of this image.

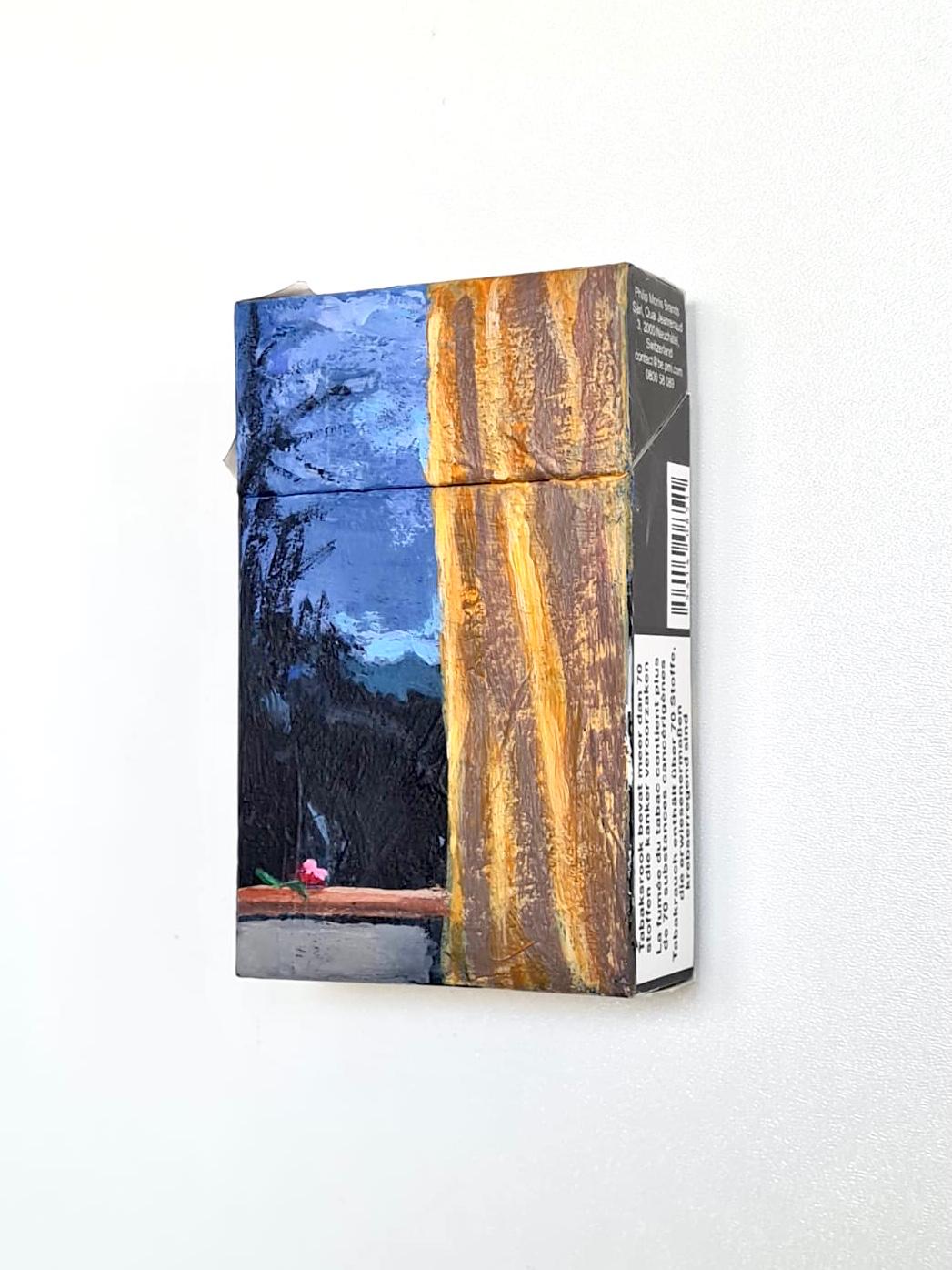

At the Window (2025) is painted on a box that remains intact. On the left, a square of deep blue and black suggests a night sky framed by darkened trees, while a vertical strip of ochre marks the edge of a wall or a curtain on the right. At the bottom, there is a small, pink flower resting on a ledge on the surface of the box, which can open and close. The piece sits at the threshold between both the interior and exterior, and may represent a moment gazing through the window looking out, or looking in from outside.

Mountain Air (2025) is looser and more abstract. Pale blues and greys smear across the flattened surface, touched with cream and darker strokes, suggesting a mountain range beneath heavy skies. The forms are indistinct, and it feels more about atmosphere, than place. Again, the cigarette box structure itself and its creases, edges, and folds suggest impermanence. It feels like a memory of air, a sensation that passes quickly, fleeting and incomplete.

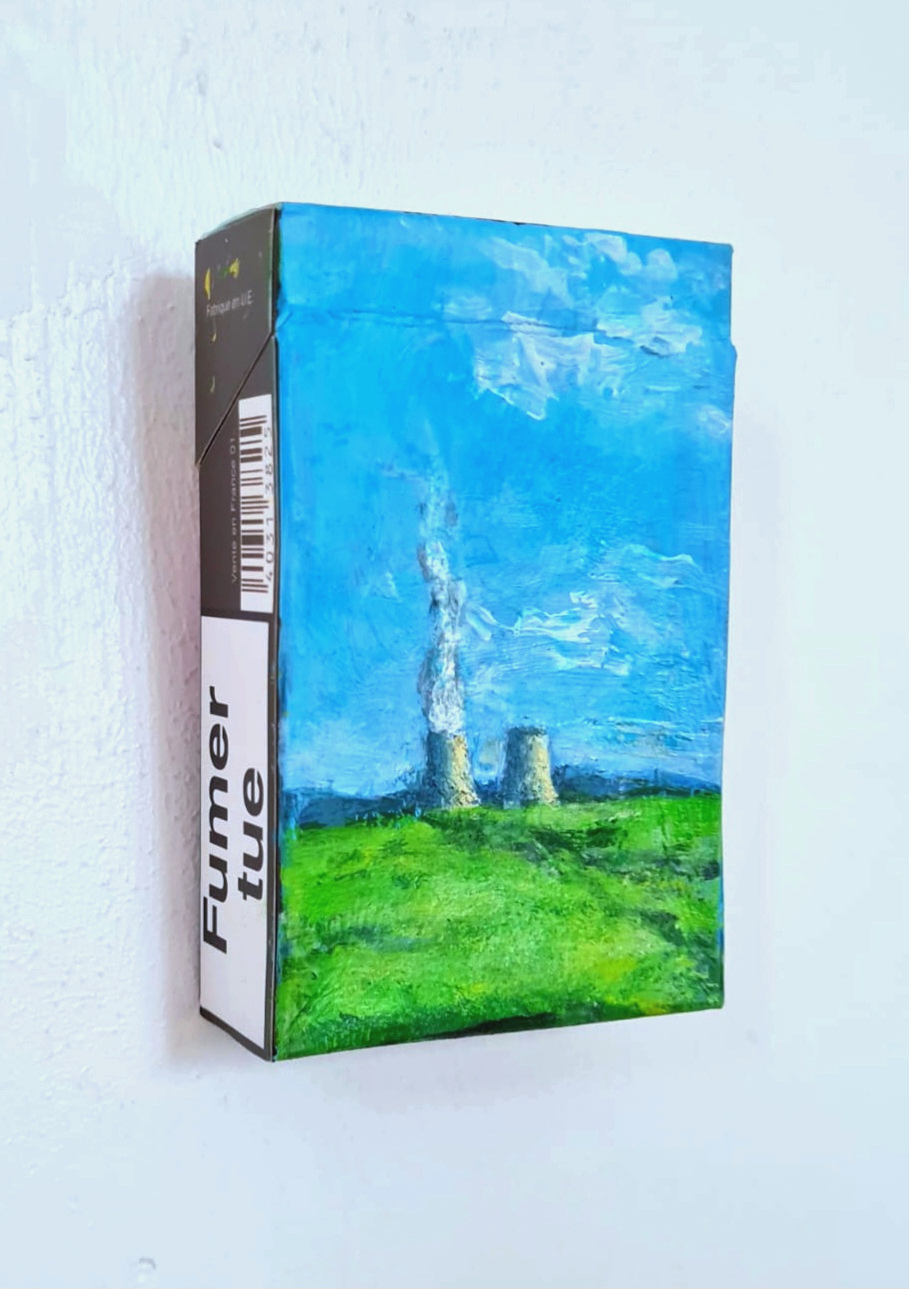

Nogent-sur-Seine (2025) was made when Hendrick was living in France. The cigarette box is intact with the French warning label down the edge of the box. Two cooling towers rise above a field of bright green; smoke rises straight up into a luminous blue sky. The industrial form is monumental and the pigments are unexpectedly serene. The work holds a contradiction, an industrial view and pollution depicted in tones associated with calmness and beauty at the same time. Hendrick does not resolve that contradiction and allows the image to sit in both spaces.

Sunset Drive (2025) depicts a road cutting into the darkness and the headlights of a car catching the curve all beneath the sky explodes with orange, violet and blue. The work is painted on an upright surface of a pack. It feels cinematic in scope, even though it is placed within the confines of something intended to fit in a pocket. Hendrick often works off of images on his phone, which he may edit, thinking of them like film stills; fragments that create stories when placed together. Sunset Drive retains that quality, a moment captured in a single frame that suggests a narrative, but also refuses to create one.

Two Benches (2025) captures a different moment, quiet and nocturnal. A black tree rises loosely painted against a cobalt sky, with a white moon visible in the corner, and faintly glowing streetlamp rises from in between three trunks. Below are two benches lower down, their empty presence and markers of human life in such a still moment. There is a quickness to the way it is painted, with thick strokes, and yet the stillness is compelling. It is a moment of everyday life, but to situate it on the surface of a cigarette box makes it ordinary and strange simultaneously.

The cigarette paintings are not seamless objects. They do not hide what they are painted on. The warning labels in different languages remain visible, a reminder that these are discarded materials, tied to specific places and to the body. Hendrick talks about the sense of lightness, of viewing the world from a distance, that the series suggests. The cigarette pack itself carries associations of habit and transience, of pleasure and risk, and those qualities remain even once paint has covered most of the surface.

The work does not attempt to erase the digital either. Many of the paintings originate in phone images, which Hendrick describes as an extension of his body. The phone captures fleeting impressions, organizing them into sequences that only make sense later, after the moment has passed. Kierkegaard’s line that life can only be understood backwards but must be lived forwards is central to this process. The paintings are not immediate transcriptions of experience but reflections built after the fact, subjective constructions shaped by memory and art history.

Hendrick has been influenced by painters like Susan Rothenberg, Milton Avery, and Félix Vallotton. Like Hendrick, they were interested in representing the beauty of the everyday, often by way of simplification and atmosphere. Rothenberg’s gestural figuration, Avery’s flattened fields of color, Vallotton’s sharp edges of light and shadow, all resonate on Hendrick’s small surfaces. And the cigarette packs are akin to collage and found materials: from Kurt Schwitters’ Merz constructions to more contemporary artists who continue to explore painting almost defiantly as entirely sculptural practices.

The exhibitions Hendrick has conducted trace his mobility. He has exhibited work in places such as Glasgow, Sofia, Istanbul, Pleven, and Marnay-sur-Seine, and is about to present a solo exhibition in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Each series carries marks of where the works were literally produced, both in subject matter but also in the materials themselves. The labels warning that cigarette smoking is hazardous, whether they are in Bulgarian, French, or English, aren’t just surface references; they are evidence of the geography of the object.

The image from the studio—the photograph of Hendrick at work—reiterates and reinforces this portability of practice. The tools, brushes, paint, flattened packs, an uncomplicated–small portfolio of tools of practice. And the idea of a studio is not, and should not, be fixed in place. These works can exist anywhere. The work itself is easily carried. The scale is modest, but the ambition is much larger, the landscape compressed into surfaces never intended for permanence.

Hendrick’s cigarette paintings are accentuated by this tension between fragility and endurance. The packs themselves are objects meant to be discarded, objects with associations based in consumption, objects with connections to transience. Within the paintings, however, Hendrick extends permanence into their surface, celebrating moments in hues, linking memories to scenes or figures through color and brushstroke. These artworks never reconcile the two polar tensions, so it remains and asks the audience to hold both, to acknowledge their simultaneous measurements.

In this time of non-stop images on the screen, Hendrick is insistent on the physical, the tactile, the intimacy. While the paintings feel small, they expect close looking. The small paintings do not compete with the phone, but rather collaborate on the screen, taking a quick digital impression and rendering a physical mark. The outcome is a body of work that does not feel measured, feels contemporary and grounded, playful and serious, light and emotional, similarly.

Brandon Hendrick’s pack paintings are about seeing, then, not just the pack images–its a rainy day, a sunset, a drive, a couple of benches–but about how images survive, how memory attaches to the pack, how something that is long-used, something disposable, holding permanence when the oil pigment comes through and transforms it. They articulate narrative without naming it, allowing viewers to supply their own dor on the surface, and the gesture of smoking a cigarette, the lightness of the smoke drifting, the brief act, storing what is there, finds some strange echo in these small landscapes. They linger for a moment, and then hold onto you longer than expected.

The cigarette paintings will be on display at 813 Microgallery in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in November 2025.