Seeing Mizuki Tanahara’s installations often seems like finding yourself in the middle of scrolling and realizing there are invisible hands controlling the flow of information. These installations do not rely on spectacle; they create moments of awareness, allowing viewers to see familiar technologies in unfamiliar ways, which allows viewers to think about the extent to which their perceptions have been edited by technology prior to viewing.

This way of thinking sits at the heart of A Map of Algorithmic / Random Walks, one of her most resonant recent works. Tanahara walked through London once, switching every fifteen minutes between letting Google Maps dictate the shortest route and letting dice decide her next turn. By layering these two modes of decision making, she built a three-part spatial map that reveals how differently we read a city depending on the logic guiding our movement, and how the information we absorb truly moves with it.

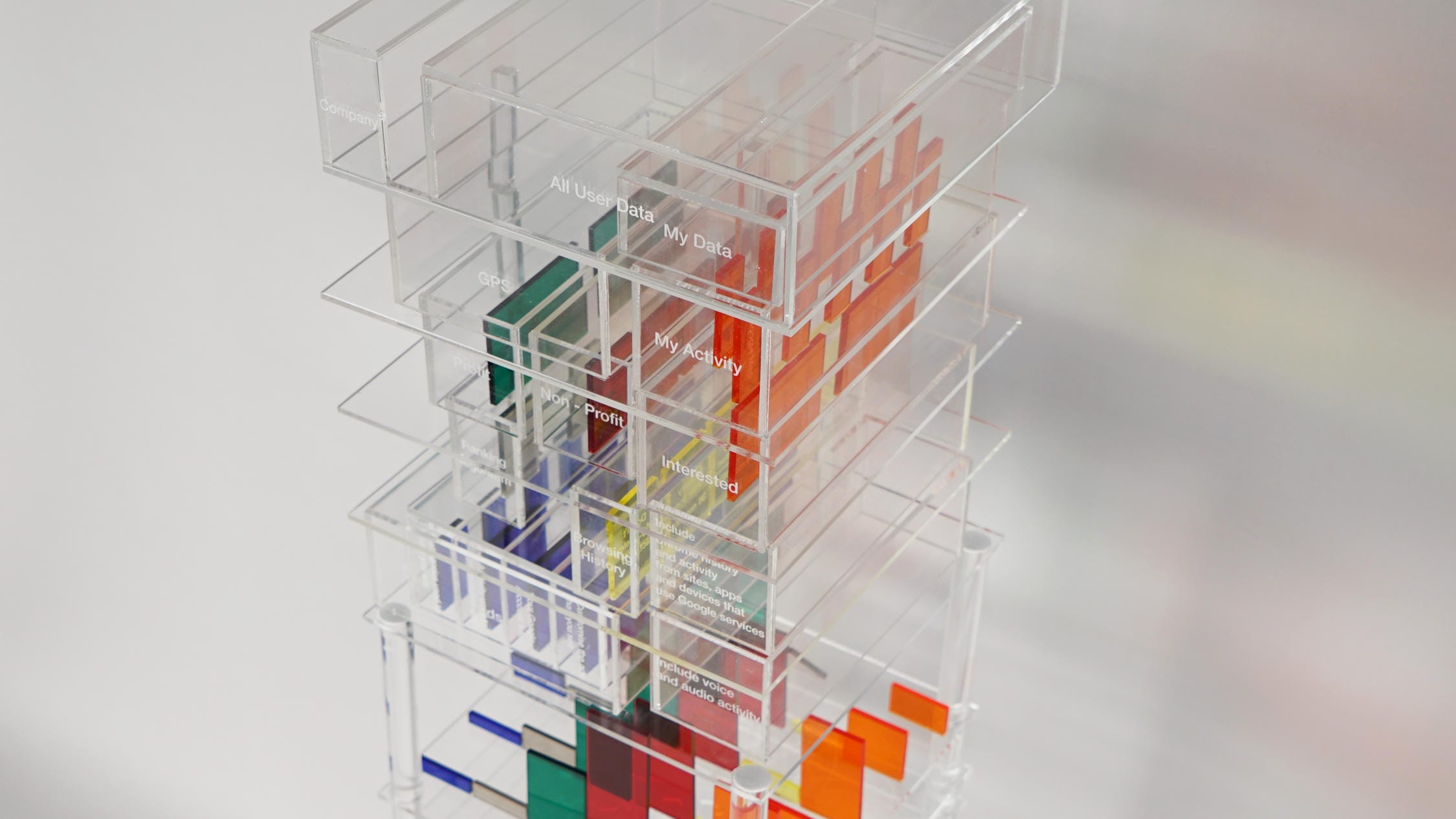

In one panel, Tanahara broke down the logic of Google Maps into six categories and showed viewers how the system works. This was not done to accuse users of relying on the system but to provide transparency, something many digital systems fail to offer. She then compared the Google Maps’ version of London to her own version of the city. Her version of the city was created using a network map of phrases and sensations from her random walk. The contrast between the two versions of London could not be greater. Google Maps’ version of London is orderly, logical, and completely filtered for efficiency. Her version of London is chaotic, intuitive, and full of unexpected details that arose only because she did not follow the path of least resistance. The third part of the installation compared the structure of both routes and provided a visual representation of two very different cities: one designed for ease of use and another that unfolds as a result of curiosity.

It is the honesty of the installation that creates the impact. Tanahara does not argue that maps are dangerous; instead, she asks a question regarding the extent to which we allow convenience to become our default way of experiencing the world, and whether we replace curiosity with algorithmically determined choices. The installation provides a gentle reminder that wandering, whether physically or mentally, is something we are slowly forgetting to do.

Similarly, the need to bring back a sense of presence is also evident in Taki-Bi (2018). Taki-Bi is an installation built upon the traditional ritual of sitting around a fire and sharing time together. Initially, the installation appears to be a communal object, inviting strangers to sit together without requiring any kind of negotiation. However, Tanahara implements a simple rule: if you want to charge your phone, you will need to place it on the charging device and leave the area until it is finished charging. That brief, forced pause when standing in a crowded space, phone-free, becomes the focal point of the installation. Strangers wander around each other awkwardly yet curiously, rediscovering the small social interactions we usually avoid by retreating into our screens.

Taki-Bi draws inspiration from a long-standing human behavior rhythm. People have sat around fires for centuries not only to cook, but to converse, to wait, and simply to exist together. Tanahara brings back this ancient rhythm in a modern context, and utilizes it to question the comfort of our individual digital bubbles. While Taki-Bi does not judge anyone for their habits, it presents a different perspective: a perspective in which physical presence may take precedence.

Tanahara’s critique of digital authority becomes more defined in Big Brother (2020), an installation that explores how numbers have replaced spiritual or political leaders as the primary influence that shapes our daily lives. Traditionally in Japan, families hang images of ancestors or highly respected figures on high places in their homes as a symbol of guidance. Tanahara replaces these with the logic of metrics: ratings, scores, predictive models, and algorithmic value. The resulting installation is uncomfortable, yet familiar. Today, we live in a society where numbers dictate worth, visibility, opportunities, and even morality. Tanahara echoes traditional practices of placing revered objects on high places by illustrating how quietly we’ve placed data into an almost sacred position. The question that hangs above the installation is simple but daunting: who governs us in this day of age?

Across her works, Tanahara returns repeatedly to the question of how digital systems quietly shape our behaviour. Indeed, sooner than eyeing on the technical mechanics behind certain projects, she uses tools like privacy interfaces, questionnaires, and playful decision making systems to reveal how easily we adapt to the structures set by big platforms. Her installations invite people to notice the habits they’ve absorbed and the assumptions they rarely question, using digital life less as a set of tools and more as an environment that influences identity, agency, and emotional state. Through these participatory experiences, she opens up space for viewers to consider how much of their online behaviour is chosen, and exactly how much is inherited from the design of the systems around them.