If you’re a social media marketer these days, you probably know the struggle of turning ordinary visuals and dull content into scroll-stopping masterpieces. The truth is, the digital landscape moves crazy fast, and the pressure to create high-quality content consistently is unreal.

That’s where AI-powered tools come in, giving marketers, content creators, and small business owners an edge that used to take teams of designers or hours of painstaking edits to achieve. From generating unique images to enhancing blurry photos with an AI image enhancer, AI can seriously step up your game, if you know which tools to pick. Here’s a breakdown of the essential AI tools every social media marketer needs in 2026.

1. Artguru – Transform Your Photos and Videos Instantly

When it comes to making low-quality photos look professional, nothing quite hits like Artguru. This AI enhancement toolkit is like having a digital Photoshop wizard in your pocket. Whether you’re a hobbyist taking bird photos or a small business owner needing high-res product images, Artguru’s suite covers all the bases.

Artguru isn’t just a photo enhancer. It’s a full-blown visual transformation engine. Artguru uses generative AI and super-resolution tech to bring your images to life; it can increase resolution of image up to 8K and enhance text so blurry PDFs become readable masterpieces. Old photo? No worries – its restoration feature removes scratches and revives faded colors like a time machine. Even videos aren’t left behind, with an HD video enhancer that’s surprisingly fast.

Some real-world uses include:

- E-commerce: Upscaling low-res logos or product shots for prints and websites.

- Education & Print: Making scanned documents sharp and readable.

- Marketing: Converting tiny images into professional website banners.

Artguru works on web, iOS, and Android. It has a free plan with daily credits and watermarked downloads, while premium plans unlock batch processing, high-resolution downloads, and faster speeds. If you’ve ever struggled with fuzzy visuals slowing down your content production, Artguru is basically your personal AI content assistant to unblur image and make it look professional.

2. Wrizzle – AI Writing Built for Real Work

Wrizzle is an AI writing tool that feels like it’s made for actually getting stuff done, not just casual tinkering. Its slogan, “write smarter, not harder,” isn’t marketing fluff—it shows up in practice through more than thirty AI writing tools designed to tackle everyday content headaches.

Instead of one generic text generator, Wrizzle organizes tools into categories: general writing, text optimization, marketing and business, and personal communication, which oddly ends up saving a lot of time. It can handle everything from SEO articles, emails, and stories, to headlines and titles, and it also sharpens existing content with paraphrasing, summarizing, and grammar fixes. The output feels polished but slightly imperfect, just enough to feel natural and human-like.

For marketers, this is a game-changer. Drafting social posts, blog entries, or email campaigns becomes less of a chore because Wrizzle produces content that’s immediately usable while leaving room for your own brand voice.

3. Canva – AI Meets Design Simplicity

You may be familiar with Canva – however, the new AI-powered features elevate it more than just a simple drag-and-drop editor. The AI image generation along with the design suggestions allow you to convert concepts into high-quality visuals within minutes. The templates not only adapt to your brand colors and fonts but also to the different post sizes for the various platforms.

Canva’s AI operates with powerful features, such as background removal, offering color palettes, and even creating design elements based on the provided text. All this is a huge step for the marketing team as it means less editing, faster approvals of the same content, and maintaining a similar look across marketing campaigns.

4. Nano Banana – AI Image Generation on Demand

On occasion, stock images fail to meet the required standard. Google’s Nano Banana enables marketers to produce one-of-a-kind, premium-quality pictures using Artificial Intelligence. You are able to provide imaginative writing and immediately get visuals that are designed according to your brand’s look and feel.

The flexibility of Nano Banana is what differentiates it from others: you can produce unreal imagery, lifelike pictures of products, or even social media banners without engaging professionals in photography or modeling. This is indeed a great option for micro-businesses that have limited funds or those who are testing the waters of content creativity.

5. Photoroom – Create Marketing Assets in a Snap

Photoroom is a service that transforms unprocessed photos into smooth and professional images. It brings together background elimination, artificial intelligence object recognition, and composition tools. Picture a case where an ordinary product photo is transformed at once into a neat e-commerce picture that is ready to start selling in your online store.

Photoroom is a great tool for influencers and small business proprietors who require a lot of quality visuals that are consistent with the brand but do not possess a full-fledged design team. The user-friendly interface of Photoroom renders complicated editing tasks nearly validation.

6. Unsplash – The AI-Friendly Image Library

Even with AI generation and enhancement, stock photos still play a vital role. Unsplash provides a vast library of high-quality, royalty-free images. Many marketers use these as a base, then enhance or customize them with AI tools like Artguru or Nano Banana.

The combination of AI tools and Unsplash means you’re not limited by your own photography skills. You can start with a strong visual foundation and tweak it to perfectly fit your brand voice.

How These Tools Work Together for Maximum Impact

The real magic happens when you combine these AI tools in a workflow. For example:

- Grab a stock photo from Unsplash.

- Enhance it in Artguru for higher resolution and clarity.

- Generate variations or complementary visuals in Nano Banana.

- Refine the image in Canva or Photoroom for layout and composition.

- Write the caption in Wrizzle, optimized for engagement.

This combination turns what used to take hours—or even days—into a streamlined, efficient process. Social media marketers can create professional content consistently, even with small teams or solo.

Conclusion

The utilization of AI tools is a must in social media marketing. Artguru, Wrizzle, Canva, Nano Banana, Photoroom, and Unsplash are among the platforms that assist in image improvement, visual creation, and creative copywriting. In case of individual use or working as part of a brand, these applications assist in the process, reduce the time taken, and improve the quality of the content, thereby making your social media strategy cleverer and quicker.

Dry Cleaning are back with their Cate Le Bon-produced album,

Dry Cleaning are back with their Cate Le Bon-produced album,

Jenny Hollingworth, half of Let’s Eat Grandma, has come out with her debut solo album,

Jenny Hollingworth, half of Let’s Eat Grandma, has come out with her debut solo album,  Zach Bryan has released a new album, With Heaven on Top. It spans 25 tracks, putting it somewhere between 2024’s The Great American Bar Scene and 2023’s Zach Bryan in terms of runtime. It was written, recorded, and produced by Bryan over the last several months in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “Hope you don’t hate it,” Bryan wrote upon announcing the album on Instagram earlier this week. It’s too pleasant to hate, but way too monotonous make it worth revisiting.

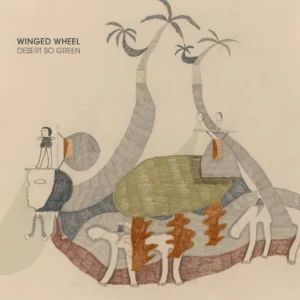

Zach Bryan has released a new album, With Heaven on Top. It spans 25 tracks, putting it somewhere between 2024’s The Great American Bar Scene and 2023’s Zach Bryan in terms of runtime. It was written, recorded, and produced by Bryan over the last several months in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “Hope you don’t hate it,” Bryan wrote upon announcing the album on Instagram earlier this week. It’s too pleasant to hate, but way too monotonous make it worth revisiting. Winged Wheel is a band that includes Whitney Johnson (Matchess, Circuit des Yeux), Cory Plump (Spray Paint), Matthew J. Rolin (Powers/Rolin Duo), Steve Shelley (Sonic Youth), Lonnie Slack, and Fred Thomas (Idle Ray, Tyvek). You could practically them a supergroup. The patient, exploratory Desert So Green is their third album, following 2024’s Big Hotel. Working out of a studio on the outskirts of Chicago, the band embraced a more cohesive approach, foregoing some of the jammy tendencies of their previous records for deeper experimentation.

Winged Wheel is a band that includes Whitney Johnson (Matchess, Circuit des Yeux), Cory Plump (Spray Paint), Matthew J. Rolin (Powers/Rolin Duo), Steve Shelley (Sonic Youth), Lonnie Slack, and Fred Thomas (Idle Ray, Tyvek). You could practically them a supergroup. The patient, exploratory Desert So Green is their third album, following 2024’s Big Hotel. Working out of a studio on the outskirts of Chicago, the band embraced a more cohesive approach, foregoing some of the jammy tendencies of their previous records for deeper experimentation.