Gaming is a fascinating world and one that you might want to explore in a little more depth. Perhaps you love playing games in your spare time or maybe you grew up with games when you were a kid? There are lots of millennials who passed from one games console to the next before eventually moving onto their own gaming PC. One of the great things about gaming is that there’s a different type of game for every person. For instance, you might love shooting games, RPG, or MMPGs. You could even adore solving puzzles. This is one of the reasons why if you’re looking to dive deeper into this world the possibilities are virtually endless. So, let’s explore a few of the best options here.

Develop Your Own

First, you might want to think about developing your own game. You might think that developing your own game is difficult or complicated. However, we’re happy to say that’s not the case. For instance, you may want to explore options such as Dreams. Dreams is a game for the PS4 which, using the Playstation Move controllers will allow you to create your own game from scratch. It’s designed to be userfriendly while also helping you to understand the tools necessary to create your own platformer game. Other games have toyed with this idea too. For instance, Little Big Planet allowed you to create your own levels. Similarly, there are other games like Minecraft that allow you to create your own worlds that you and other people can explore. The creator tool in Fortnite provides a similar feature. However, these are surface builders. That means that you are using existing software to create a game in a tool box that has already been created.

What if you want to create your own tool box? To do this, you need to learn how to code software. Coding isn’t something that you can just jump into. However, you can learn how to code in about three months on a basic level. You will then be able to take steps to expand your knowledge overtime.

Start Cosplaying

Another option would be to cosplay. Cosplaying can be great fun if you have an affinity towards a certain character or series of games. It’s one of the ways that you can show your love and passion for a title while becoming a more active part of the community. This is something that you can do through professional channels or as an amateur. If you want to be an amateur cosplayer, then you can think about creating your costumes from scratch and working to make improvements. You can post videos online and share them with what is often a highly active and excited community.

Alternatively, you might want to think about becoming a professional cosplayer. You can do this by putting money into your costumes and promoting yourself across social media. Some social networks are going to be more useful than others. For instance, you might want to focus on using options such as Instagram because it’s easier to share your photos and videos. It’s also great to encourage an active community of followers. Getting highly active followers is critical to ensuring that you are a success online and do gain the right level of attention.

Attend Events

If you want to get more active in the gaming community, then you could think about attending different gaming events. This is also a great way to reach and engage with key individuals in the industry from developers to producers. It’s great if you want to be noticed. There are lots of different types of events too. For instance, you could head to the Cosplay Expo if you are interested in becoming a cosplayer or you’re just a huge fan. You’ll often find voice artists at these types of events too.

Alternatively, you could attend an event like E3. The buzz around E3 has died down as of late. This is in part due to COVID-19. However, it’s likely that since the situation around COVID has improved dramatically, interest in live events like this will pick up again quite soon. Some incredible announcements have been made at events like this in the past.

Game Professionally

Are you skilled at a particular game or title? If so, then you can think about gaming professionally. Some people actually earn a fortune gaming on a professional level with prizes that can be in the high millions for popular titles such as Fortnite. You’ll need to spend time developing your skill and you should be committed to constantly improving. There are different types of competitions. For instance, there’s speed running. The aim here is to get through a single player game as quickly as possible. Often, this will involve beating a game that should take at least ten hours in about two or maybe less.

For online games, there are tournaments where you can enter on your own or play with other people in your team. If you are fantastic at a key title then you will have no trouble gaining attention and you might even receive sponsors. This is key to earning money as a competitive gamer.

Start Streaming

Another way to game professionally would be to start streaming your progress on games. There are lots of people who have great fun streaming through sites like Twitch. Some people also garner a lot of attention. Often, the trick to getting attention streaming games is all about showing a personality. You need to stand out from all the other people who are vying for the same audience. It can take a while to build up an audience as a streamer, but it can also be quite a rewarding and exciting experience too.

Become A Tester

Finally, you might want to think about becoming a tester. Testing games will allow you to work behind the scenes of the gaming industry. It’s a cool option and one provides you with the option to see games before they are ready for the market. As such, you might just gain some insider knowledge on new titles. That said, a game tester isn’t quite as exciting as it might sound because you will have to run through the game to check for bugs and glitches. This means that you will be playing the same levels on repeat, often testing different routes through the game. But it can still be fascinating to discover this process. It can also be a step towards developing a game yourself. You can learn what goes into making a new title a success. Do be aware that less companies are paying testers these days. Instead, they are giving communities the chance to access beta versions of online games. That way, they can report on any bugs and give developers all the feedback they need to improve the titles.

We hope this helps you understand some of the key steps that you can take if you are keen to take your gaming journey to the next level. By exploring the right possibilities here, you can make sure that you get more out of this experience. This could be true regardless of whether you are thinking about looking for ways to make money from gaming or simply guarantee that it is far more enjoyable overall. The trick here is to not limit your options and instead explore a variety of exciting horizons. Only then will you be able to unlock everything that gaming has to offer and ensure that you are not missing out on some fantastic opportunities.

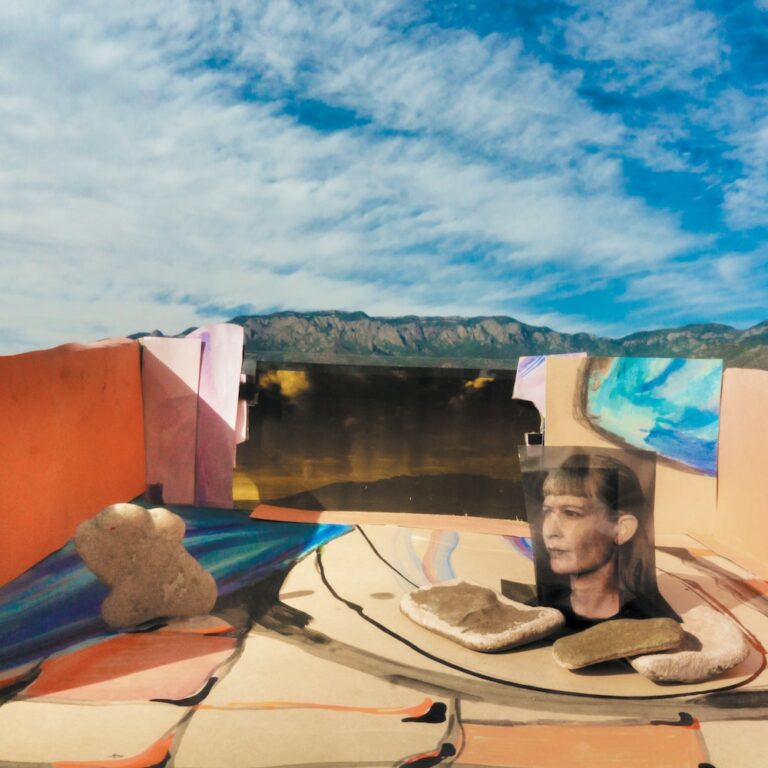

Jenny Hval has released

Jenny Hval has released  Maia Friedman, known for her work with Dirty Projectors and Coco, has issued her debut solo album,

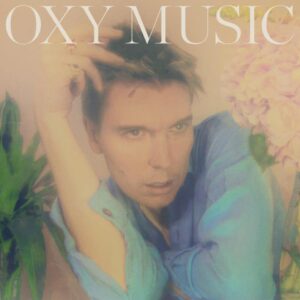

Maia Friedman, known for her work with Dirty Projectors and Coco, has issued her debut solo album,  Alex Cameron is back with a new LP. It’s called

Alex Cameron is back with a new LP. It’s called  Drug Church have put out their fourth album,

Drug Church have put out their fourth album,  Richmond, Virginia rapper Fly Anakin has dropped his debut full-length,

Richmond, Virginia rapper Fly Anakin has dropped his debut full-length,

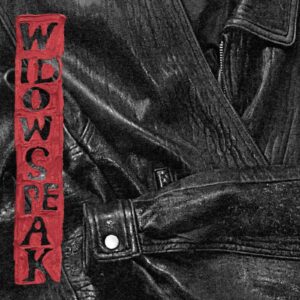

Widowspeak

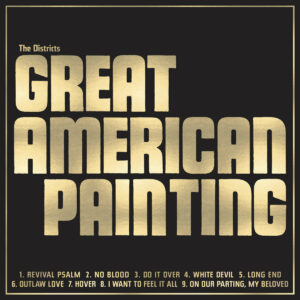

Widowspeak The Districts have a new album out via

The Districts have a new album out via