With every new year comes the drive to try new things and learn a new set of skills before going into the next one – and that’s why you should have an open mind while looking out for new hobbies you should be trying this year. It’s still very early in, and you’ve got plenty of time to try some things out.

Spending the whole year and your free time lazing around or doing the same old activities can get dull, and doing something new a fresh will help to keep your current interests fun and entertaining. If you put all of your focus onto one thing, it will just lead to burnout.

Writing

Everyone has creativity in them that they need to get out, and there’s no better way to do so than writing. A lot of people are afraid to write their ideas out, worried that they might not be able to do their stories any justice without the right skills. While that might be the case early on, until you get into it – you’re never going to be able to write as you would like to. If you’re going to get things done, you need to practice them enough and correctly. Creative writing is a great hobby to get into, and it doesn’t have to lead anywhere or serve any purpose other than being fun.

Songwriting

Another way of getting creative and expressing yourself is songwriting. It’s an amazing combination of writing, musical production, and instrumental play at its best. You get to craft beautiful stories with songs or capture moments in time that will forever be enshrined in memories. Like with writing, you don’t have to be a master musician to start engaging in this hobby – you just need to have the passion and drive for it. You may even explore the power of an AI song generator to get started or take your songwriting to the next level. These tools allow you to create songs in minutes, even if you have no prior musical training. Just remember to use it as a tool and not as a replacement for learning the basics of songwriting.

Blogging

If you like the idea of writing but want to keep it about your life, you should consider starting a blog. Many people start blogs with the idea of sharing their day to day life, like a diary, and it can be a wonderful way of getting your thoughts out there. You don’t necessarily have to blog about something interesting, and some readers might find it calming to read about the tame daily activities.

Some bloggers don’t even write with the goal of having others read it, as the idea that your thoughts and feelings are out there is enough to be cathartic. Sharing your emotions is can sometimes be a nice feeling, and a blog is a great format to try it in – it can be completely anonymous!

Embroidery

Embroidery is something a little bit different to the typical hobby, but it has its perks if you can get good at it. Businesses like Mato & Hash offer embroidery services to make your clothing and items a lot more attractive – which is something you could do at home if you were willing to put in the time. However, note that it might take a bit of investment if you were to get the tools and machinery necessary to learn.

Illustration

One skill that barely needs any investment to get into is illustrating. Illustration or drawing is a hobby that doesn’t really have any limits or requirements. All you need is a piece of paper and a pen or pencil, and some idea of what to draw. You can draw anything you like, so long as you’re not afraid of how it will turn out. Even if you haven’t got any ideas, you could just draw what’s in front of you. If you keep developing it, it’s something that could lead to a career later down the line.

It goes beyond the traditional mediums, too. Digital art has been a growing industry for years now, and it offers a similar yet completely different experience. However, if you’re going to do things digitally, you’re going to need the right equipment – and that can set you back.

Sculpting

Sculpting is a hobby that’s been around for thousands of years, and it’s never too late to start. Like illustration, you can sculpt nearly anything you want to, but you need the materials. Clay is typically the most used, and you can reuse it as much as you want to if you’re not happy with how it turns out.

For some people getting their hands dirty and sculpting everything is therapeutic, and it could be a great way for you to release your stress. Just make sure you’ve got the space to do it and the tools that help you work with it! Trying to work the clay with your hands alone limits the things you can do with it.

Photography

It’s not often that we take the time to stop and appreciate what’s around us, and photography can help you open your eyes to it. When you walk past a river, or when you’re walking through a park, how often are you trying to see the scene for what it is? Once you pick up a camera and start looking for the most appealing angles, you start to see things for what they really are.

It’s not just about finding the right scenes to appreciate, but you’re taking a picture to remember them by. More pictures of times with family and friends places that you’ve visited and that you’re fond of. You’ll get to see life with a new perspective, one that lets you better share what you see with others.

Photography can also translate into a job opportunity if you’re good at it and actively seek out captivating images.

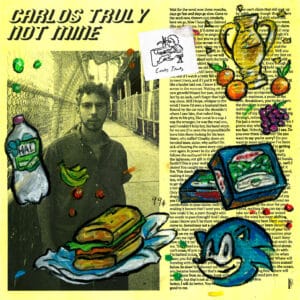

Scrapbooking

If you’re the type of person who likes to record the bigger events in their life, scrapbooking might be for you. It also fits nicely with photography and writing, and you could consider it as a way to expand on those hobbies. Get creative and stuck in while compiling all of the major events and fond memories that you have, while putting them in a format that’s fun and lively. Not everything has to be left as just a picture, or just a piece of writing – why not turn them into your own personal work of art?

Baking

If you’re not adept in the kitchen, the idea of baking might not sound like your ideal hobby. Just know that baking and cooking are not the same at all, although they may use a lot of the same equipment. With baking, it’s not just about trying to work out the best ingredients, instead, you’re trying to follow a recipe to the letter. There’s a lot less that can go wrong, and it’s worth giving a shot if you have a sweet tooth.

Many people find the whole process of baking to be quite therapeutic and calming, and it also opens opportunities for you to share with others. No one is going to complain about a surprise batch of cookies or cupcakes, and you’re likely to have a lot of excess food if you partake in baking regularly.

Gardening

Gardening is a great hobby for many reasons. First of all, you’re doing something with your home and actively making your garden a more appealing and attractive area. A lot of people ignore their gardens and let them get out of hand, but taking up gardening will give you a reason to do something with it.

Gardening as a hobby can also yield you your own produce. Being able to grow your own fruit and vegetables is a very satisfying feeling, and something you should give a try even on a small scale. It’s easy to get attached to your plants, especially once you start to get a good understanding of how to grow your plants.

Learning music

If you didn’t start to learn an instrument at an early age, you might be feeling as if it’s too late for you. A lot of great musicians started as children, but that doesn’t apply to every single famous musician out there. You can pick up and master an instrument at any time if you’ve got the time and drive to do it. The key is being able to manage your expectations and find lessons that are well-structured. You need to be taught in a way that you can see your progress, and that has proper direction. Trying to do things that are too difficult for you early on can be very discouraging.

If possible, live lessons might be the best option for you, as they can make sure that you’re practising properly and correct you where you might be struggling.

Start a podcast

If you’ve always wanted to share your thoughts on things or thought that a lot of the discussions you had might be entertaining for others to watch or listen to, a podcast could be a good format for it. Podcasts have been increasing in popularity through the years, and many people like to listen to them in their free time or when they’re getting things done. Your podcast could be the reason someone’s commute to work isn’t as tedious as usual, or that their evening run goes by in a flash.

Podcasts can lead to opportunities to speak with people that you’ve looked up to live and have those same discussions with them. If your podcasts grow big enough and attract the right attention, it could even be something you do for employment. Many large podcasts generate enough revenue to live off of if done consistently enough.